Chapter 21 Articular Cartilage Injury and Adult OCD

Treatment Options and Decision Making

Osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) is a pathologic process in which the subchondral bone and the overlying articular cartilage detach from the underlying bony surface.10,40,55 The disease results in subchondral bone loss and destabilization of the overlying articular cartilage, leading to separation and increased susceptibility to stress and shear.43 Fragmentation of both cartilage and bone leads to early degenerative changes and loss of function in the affected compartment. The true cause is unknown but is likely related to repetitive microtrauma, an acute traumatic incident, ischemia, an ossification abnormality, or endocrine or genetic predisposition.2,39,53

The prevalence of OCD is estimated at 15 to 30 cases per 100,000, most frequently occurring in the knee, with medial femoral condyle involvement in 80% of cases, lateral femoral condyle in 15%, and patellofemoral in 5%.27,36 The lateral aspect of the medial femoral condyle is the classic site of the OCD lesion. In addition to the knee, OCD has the propensity of occurring in the elbow, wrist, and ankle.2,10,55

Osteochondritis dissecans is divided into juvenile (JOCD) and adult (AOCD) forms.9 The distinction between JOCD (open growth plates) and AOCD (closed growth plates) may be important in treatment and prognosis. JOCD often resolves with nonoperative management and has a much better prognosis compared with adult OCD, which, once symptomatic, can follow a progressive, unremitting course.

Presentation

On physical examination, patients present with tenderness overlying the OCD region. Patients often present with an antalgic gait. If the OCD lesion is present in the classic location, the lateral aspect of the medial femoral condyle, the patient will ambulate with the affected leg in relative external rotation (Wilson sign) to decrease contact of the lesion with the medial tibial eminence. Joint effusion, decreased range of motion, and quadriceps atrophy are also variably present, depending on the severity and duration of the lesion.20,42

Imaging

Unfortunately, none of the physical findings observed during the examination can be used specifically to diagnose OCD; therefore confirmatory x-ray, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or computed tomography (CT) scans are required. Plain x-ray films should include standard anteroposterior, flexion weight-bearing anteroposterior (tunnel view), lateral, and Merchant views (Fig. 21-1). Flexion weight-bearing anteroposterior in addition to standard anteroposterior allows better visualization of lesions along the posterolateral aspect of the medial femoral condyle.26 Radiographic images of patients with adult OCD show a lesion that typically appears as an area of osteosclerotic bone, with a high-intensity line between defect and epiphysis.

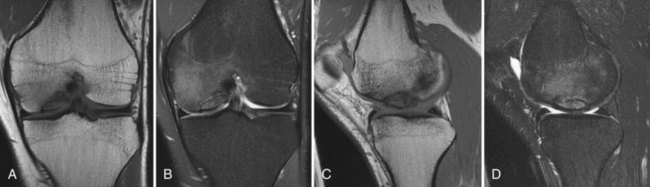

MRI is the mainstay in the diagnosis of OCD lesions and is the most informative imaging modality in the preoperative workup of OCD. Specifically, the quality of bone edema, subchondral separation, and cartilage condition are evaluated before treatment.1 MRI can reliably indicate lesion size, location, and depth, providing insight into a patient’s knee condition (Fig. 21-2). MRI images are assessed according to the criteria presented below; meeting one of the four criteria offers up to 97% sensitivity and 100% specificity in predicting lesion stability.15,16,20,43

Furthermore, OCD lesions can be classified by MRI findings according to whether the lesion is attached, partially attached, or completely detached from the parent bone37,43,49 (Table 21-1).

Table 21-1 MRI Staging for Evaluation of Osteochondral Fracture27,33,38

| Stage | MRI Findings |

|---|---|

| 0 | Normal |

| I | Signal changes consistent with articular cartilage injury, without disruption, and with normal subchondral bone |

| II | High-grade signal intensity; breach of the articular cartilage with a stable subchondral fragment |

| III | Partial chondral detachment with a thin high-signal rim (on T2-weighted images) behind the osteochondral fragment, representing synovial fluid |

| IV | Loose body in the center of the osteochondral fragment or free in the joint space |

Etiology, Natural History, and Prognosis

The definitive cause of OCD has yet to be established. A number of factors may contribute, such as repetitive microtrauma, acute stress and injury, restricted blood supply, endocrine abnormalities, and genetic predisposition.2,39,53 Physical trauma is thought to be one of the major contributory factors in the development of OCD. Repetitive trauma to the joint leads to redundant healing and fibrosis, interrupting the blood supply to subchondral bone and possibly leading to avascular necrosis.13 In adults, high-impact sports such as soccer, basketball, football, and weightlifting may put a participant at higher risk of developing OCD. Endocrine abnormalities affecting calcium and phosphorous homeostasis or anomalies of bone formation can compromise the blood supply to subchondral bone and progress to avascular necrosis. Recent reports have suggested a genetic predisposition to OCD.39

Most adult OCD cases arise from established but untreated or asymptomatic juvenile OCD. However, many patients with adult OCD present with a history of knee pain that began when they had open physes. These cases probably represent juvenile OCD that did not heal and evolved to adult OCD. An exception to this progression is juvenile OCD that heals spontaneously; however, such lesions usually are not present in the classic location (lateral aspect of the medial femoral condyle).13,55 Adult OCD may also arise de novo.9,21

The natural history of untreated OCD is poorly defined. Neither the literature nor our experience allows us to definitively determine whether untreated OCD has a higher likelihood of progressing to symptomatic degenerative joint disease (DJD) in the future. Linden performed a long-term retrospective follow-up study on patients with OCD of the femoral condyles with an average follow-up of 33 years after initial diagnosis.35 The author concluded that OCD occurring prior to closure of the physes (JOCD) does not lead to additional complications later in life, but patients who manifest OCD after closure of the physes (AOCD) develop osteoarthritis 10 years earlier than the normal population. In contrast, Twyman and associates evaluated 22 knees with juvenile OCD and found that 50% had some radiographic signs of osteoarthritis at an average follow-up of 34 years.56 The likelihood of developing osteoarthritis was also found to be proportional to the size of the area involved. The authors believe that lateral femoral condyle OCD has a poorer prognosis, but not all of these cases will become symptomatic over time despite radiographic changes.

Surgical Treatment

Surgical options are considered more often than not for adult OCD, as articular cartilage presents with an inherent poor ability to repair itself. Surgical options include loose body removal, drilling of the subchondral bone, internal fixation of the fragment, microfracture, osteochondral autografting and allografting, and autologous chondrocyte implantation.9,19,21,43 The overall goal of such intervention is to enhance the healing potential of the subchondral bone, fix the unstable fragment, and replace damaged bone and cartilage with implantable tissue.

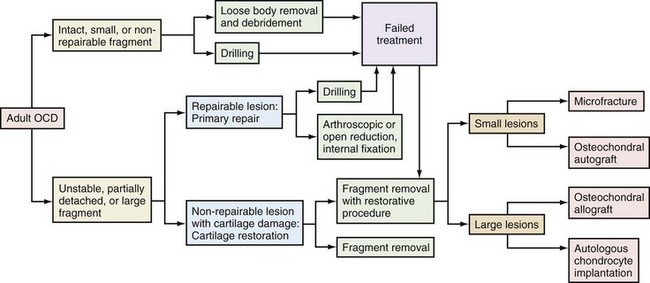

The type and extent of surgery necessary for OCD depend on the patient’s age, characteristics of the lesion (quality of articular cartilage; size of associated subchondral bone; and shape, thickness, and location of the lesion), diagnostic information provided by MRI and arthroscopy, and preference of the operating surgeon. The author’s preferred algorithm for treatment of OCD lesions is shown in Figure 21-3.

Positioning, Examination Under Anesthesia, and Diagnostic Arthroscopy

A complete diagnostic arthroscopic evaluation of the structures in each compartment is performed. When the lesions are identified, a probe is used to determine the stability of the fragment (Fig. 21-4). Guhl’s intraoperative classification is defined by cartilage integrity and fragment stability25 (Table 21-2).

Table 21-2 Guhl’s Classification18

| Stage | Arthroscopic Findings |

|---|---|

| I | Normal |

| II | Fragmentation in situ |

| III | Partial detachment |

| IV | Complete detachment, loose body present |

Loose Body Removal

In a small number of cases, when the fragment is comminuted, avascular, deformed, or otherwise irreparable, fragment removal is an isolated treatment option.3 In cases involving chronic symptomatic lesions, fibrous tissue may impede anatomic reduction and adequate healing. In addition, the fragment may be associated with only small amounts of subchondral bone with limited ability to heal.

Although OCD lesions should be reduced, stabilized, bone grafted, or restored when possible, patients with small or non–weight-bearing lesions may have good outcomes with isolated loose body removal. Ewing and Voto showed 72% satisfactory results in patients treated with fragment excision with or without drilling or abrasion.19 A recent study showed successful outcomes in 8 of 9 patients treated with loose body removal alone for small (<2 cm2) AOCD lesions.50 These results, however, are controversial and may pertain only to short-term outcomes. Anderson and Pagnani excised OCD fragments in 11 patients with JOCD and 9 patients with AOCD. At an average of 9 years postoperatively, five failures and six poor outcomes were reported, and equally disappointing outcomes were seen with JOCD and AOCD.4 Similarly, Wright and coworkers had 65% fair or poor results at an average 8.9 years postoperatively in 17 patients treated with fragment excision, and suggested the use of aggressive cartilage preservation techniques and avoidance of fragment excision.58

Reparative Procedures

The goal of reparative procedures is to restore the integrity of the native subchondral interface and preserve the overlying articular cartilage.42

Drilling

As mentioned previously, disruption of the blood supply to the subchondral bone is thought to be an important factor in the development of OCD.5 Thus, treatment incorporates creation of vascular channels to the affected region. Arthroscopic drilling can be used to generate such channels and is usually performed in young patients.1

This technique is performed using an antegrade or a retrograde approach. Antegrade drilling is performed from the joint space, through the articular cartilage, and into the subchondral bone. Lesions of the medial femoral condyle can be drilled through an anterolateral or anteromedial portal, and lesions of the lateral femoral condyle are usually accessible through the anterolateral portal. If the lesion is not accessible via standard portals, accessory portals are created to obtain an orthogonal drilling angle.5 Multiple holes are drilled using a K-wire, making certain to uniformly cover the lesion. Return of blood and fat droplets from the drilled region is used to confirm the depth of the penetration.

Antegrade drilling has the undesirable consequence of violating the articular cartilage surface causing the violation to fill with fibrocartilage. Retrograde drilling, although more difficult, avoids damage to the articular cartilage. The drill enters behind the lesion and penetrates the bony fragment without violating the cartilage or entering the joint. C-arm visualization or the use of an anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) guide is necessary to avoid joint penetration or dislodgement of the OCD fragment.32

Overall, outcomes of OCD drilling are generally favorable, and patient age is the best prognostic factor. Younger patients who have undergone this procedure demonstrate higher levels of radiographic healing and favorable relief of symptoms.5,8,18,31 Louisia and associates compared outcomes of JOCD versus AOCD, reporting radiographic healing in 71% of JOCD cases, and only 25% in adult AOCD cases.38

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree