Arthroscopic Subacromial Decompression

Susan S. Jordan

SURGICAL INDICATIONS

Arthroscopic subacromial decompression (SAD) has become an increasingly common procedure for orthopaedic surgeons in the United States. From 1999 to 2003, it rose from being the ninth most commonly reported procedure by those taking their American Board of Orthopaedic Surgery Part II to the second most common procedure (2). Recent studies have questioned the need for SAD in the setting of rotator cuff repair (3,7,8). For patients with type 2 acromions and supraspinatus tears, inclusion of SAD with rotator cuff repair did not affect functional outcome in a prospective randomized study (3). In prospective randomized study of patients with full-thickness rotator cuff tears, SAD did not affect outcome at 2 year follow-up (7). In spite of these studies, there still appears to be a role for isolated SAD for the patient with impingement and an intact rotator cuff.

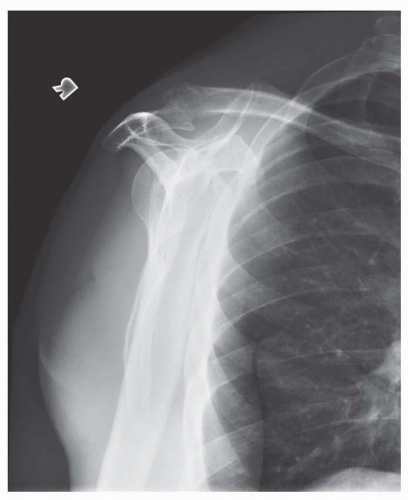

Patients with impingement syndrome typically complain of pain with overhead reaching and abduction motions. They often complain of night pain as well. On examination, there may be limitation of active forward flexion and abduction secondary to pain. Neer and Hawkin impingement signs will be positive. In addition to physical examination, the initial work up of the patient should include shoulder x-rays, with particular attention to the supraspinatus outlet view. This view best demonstrates the shape of the acromion (Fig. 12.1). Patients with large anterolateral hooks or spurs on the acromion may benefit ultimately from surgical decompression if nonoperative treatment fails. MRI may also be obtained to rule out associated rotator cuff, labral, or biceps pathology but is not necessary in every case.

An isolated SAD may be appropriate for the patient with persistent impingement symptoms that fail to improve with nonoperative management for more than 6 months. Prior to considering surgical treatment, patients should undergo an extensive rehabilitation protocol targeted at rotator cuff and scapular stabilizer strengthening. Ice and anti-inflammatory medications also help during initial nonoperative management. Subacromial injections are often helpful in treating impingement pain. Pain relief from the injection with resolution of impingement signs (Neer impingement test) is also informative; a good response to injection is associated with good results from SAD should it be necessary (6,9).

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

Arthroscopic SAD may be performed in the beach chair or lateral position depending on surgeon preference. An interscalene block may be supplemented with sedation or general anesthesia. Once the patient is positioned, the landmarks of the shoulder are marked including the borders of the acromion, the acromioclavicular joint, and the coracoid. Portal locations are marked. The lateral portal is marked 2 to 3 cm from the anterolateral border of the acromion in line with the anterior edge of the acromion. The arthroscopy is performed by establishing a typical posterior portal 2 to 3 cm inferior and slightly medial to the posterolateral acromial edge. First, the surgeon may insufflate the glenohumeral joint with a spinal needle directed toward the coracoid. Then, the arthroscope is introduced into the joint. An anterior portal just superior to the subscapularis is established to allow insertion of a probe. The joint is thoroughly inspected for any pathology, with close attention to the undersurface of the rotator cuff for partial-thickness tears.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|