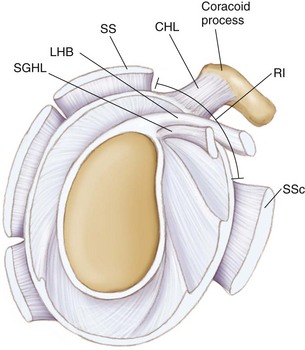

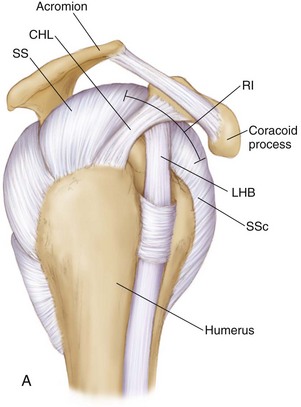

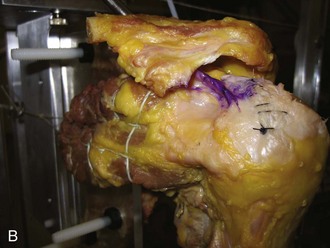

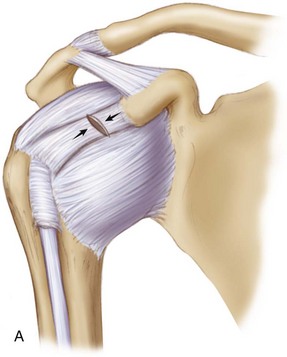

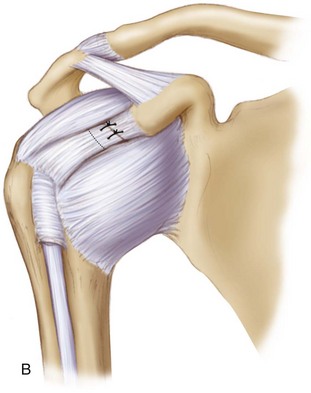

Chapter 6 The rotator interval (RI) is a triangular space of the anterosuperior shoulder between the supraspinatus (SS) and subscapularis (SSc) tendons, containing both the coracohumeral ligament (CHL) and the superior glenohumeral ligament (SGHL) (Figs. 6-1 and 6-2). Although injuries to the RI capsule have been associated with increased glenohumeral translation and subsequent instability,1,2 its contribution to overall shoulder stability remains under debate. Several reports have suggested that RI capsular structures contribute to stability by resisting inferior and posterior glenohumeral translation3–6 and/or maintaining negative intraarticular pressure,7 whereas others have shown that surgical imbrication of the RI augments surgical correction of multidirectional and posterior instability.3,4,6,8–12 Previously, RI closure was commonly performed via open surgical techniques; however, recent all-arthroscopic techniques for RI closure have been described.13,14 The debate regarding RI closure is centered around the “circle concept” of the shoulder,15 which states that if the humerus is posteriorly subluxed, there must be an opposite and obligate injury to the anterior superior structures of the glenohumeral joint (the RI). However, several studies have refuted the circle concept theory,16 indicating no injury to the RI after posterior dislocation. In addition, the premise of an open RI closure is not the same concept as an arthroscopic RI closure.3,14,17 As described by Harryman,3 open RI closure consistently imbricates the CHL from medial to lateral, which adequately restores inferior and posterior stability of the shoulder; however, this occurs at the expense of significant (30- to 40-degree) losses of external rotation (ER) at the side (Fig. 6-3). All-arthroscopic techniques have evolved to address the RI; however, the arthroscopic closure is fundamentally different from the open closure in direction of closure (arthroscopic: superior to inferior; open: medial to lateral and/or superior to inferior), in addition to differences in tissue imbricated (arthroscopic: RI capsule, SGHL to middle glenohumeral ligament [MGHL]; open: CHL or SS to SSc). Based on biomechanical evidence,12,14,17–19 there are certain indications for an arthroscopic RI closure, including certain cases of anterior instability (in the setting of hyperlaxity) and revision anterior instability (to increase the bumper effect anteriorly), multidirectional instability with laxity and sulcus sign, and possible posterior or anterior instability in the setting of hyperlaxity. The purposes of this chapter are to review the operative indications and surgical technique for arthroscopic RI capsule closure in the setting of glenohumeral instability. Figure 6-3 The coracohumeral ligament (CHL) is sectioned (A) and then imbricated by 1 cm (B), as was demonstrated by Harryman3 in an open rotator interval closure that shortened the CHL to improve inferior and posterior stability of the shoulder. This technique resulted in significant (30- to 45-degree) losses of external rotation at the side. • Original mechanism of injury (traumatic versus insidious onset) • Current symptoms (may point to alternative diagnosis) • Pain (e.g., rest pain vs. night pain) • Inability to use arm above head • Previous nonsurgical and surgical treatment of the shoulder • Activity level of the patient • Posttreatment goals; allows the surgeon to address patient expectations and to ensure that these are aligned with treatment options and outcomes

Arthroscopic Rotator Interval Capsule Closure*†

Preoperative Considerations

Arthroscopic Rotator Interval Capsule Closure