Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair

James C. Esch

Bradford S. Tucker

J. C. Esch: Department of Orthopaedics, University of California, San Diego, School of Medicine, San Diego, California.

B. S. Tucker: Department of Surgery, Atlantic City Medical Center, Atlantic City, New Jersey.

INTRODUCTION

Shoulder arthroscopy has improved our understanding and treatment of rotator cuff tears. It facilitates easy viewing from different angles, as opposed to open treatment, which, when performed through a small incision, has a limited exposure, in part, because of the acromion. This arthroscopic viewpoint has led to the recognition of several common rotator cuff tear patterns.13 Tear pattern recognition, suture anchors, and tissue-passing instruments enable the surgeon to mobilize and repair a torn rotator cuff to its bony footprint with consistency. Associated pathology within the shoulder joint—articular cartilage, glenoid labrum, and biceps tendon problems—can also be treated. The authors rely on the arthroscope to repair all rotator cuff tears.

RADIOGRAPHY AND MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING

The surgeon must carefully examine routine anteroposterior (AP), axillary, and arch radiographs. The glenohumeral space and acromiohumeral distance are carefully evaluated on the AP view for arthritis, aseptic necrosis, and calcifications. The axillary view is routinely obtained because it tells the surgeon whether an os acromiale is present. The arch view shows acromiale shape and thickness. Additionally, a weight-bearing “push-up” AP view, in which upward pressure is placed on the humerus, can be obtained to evaluate narrowing of the acromiohumeral space (Fig. 9-1).

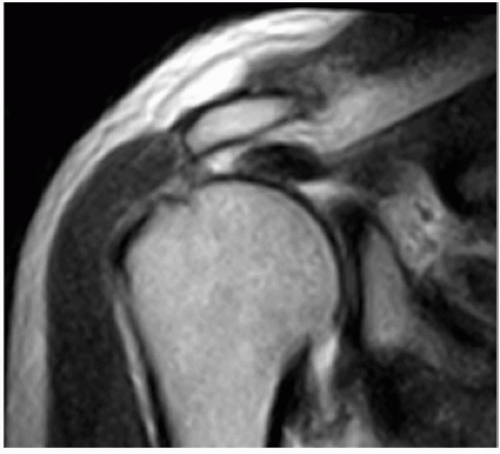

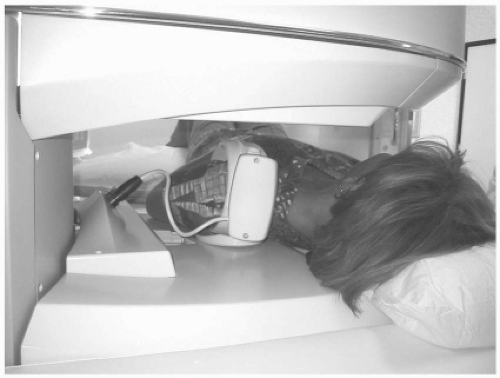

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) imparts the best image of a torn rotator cuff, showing the subscapularis tendon and status of the deltoid muscle. The size and shape of supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendon tears are revealed (Fig. 9-2), as is any atrophy within the rotator cuff muscles. Smaller scanners and newer software afford excellent images in a convenient office setting (Fig. 9-3). These scans can also be reviewed on a computer. The Orthopedic surgeon should personally review the MRI scan.

SURGICAL OPTIONS, INDICATIONS, AND DECISION MAKING

The office radiographs and MRI complement the patient’s history of symptom onset, discomfort, and loss of function. Discuss with the patient the ease or difficulty of repair, the extent of rehabilitation, and the expected result. Surgery provides good pain relief. Weakness, however, is slower to recover and will recover incompletely if there is significant muscle atrophy. Patients with significant pain are usually unaware of any accompanying weakness. The patient should have a clear idea of the goals and problems of surgery. Despite these caveats, some patients will have unrealistic expectations for surgical correction of their symptoms. Point out to the patient that an MRI obtained after surgery may show incomplete healing of the rotator cuff repair.6

Small to large tears of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons can be repaired by standard arthroscopic repair techniques. Tear size and configuration dictate the specific

surgical technique. Usually, repair requires a combination of a margin convergence and a tendon-to-bone repair using suture anchors. Margin convergence involves suturing the anterior and posterior leaves of the tear in a sequential side-to-side manner, starting medially and proceeding laterally until the tear converges toward the bony footprint. The free edge is then attached to the footprint with suture anchors. The value of an arthroscopic rotator cuff repair is a secure arthroscopic repair through smaller incisions, without disruption of the deltoid muscle attachment. The final repair is “decompressed” by smoothing the undersurface of the acromion.

surgical technique. Usually, repair requires a combination of a margin convergence and a tendon-to-bone repair using suture anchors. Margin convergence involves suturing the anterior and posterior leaves of the tear in a sequential side-to-side manner, starting medially and proceeding laterally until the tear converges toward the bony footprint. The free edge is then attached to the footprint with suture anchors. The value of an arthroscopic rotator cuff repair is a secure arthroscopic repair through smaller incisions, without disruption of the deltoid muscle attachment. The final repair is “decompressed” by smoothing the undersurface of the acromion.

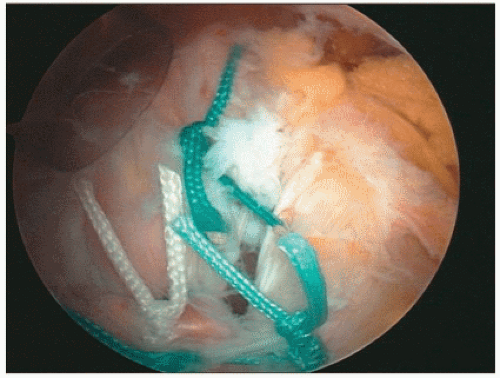

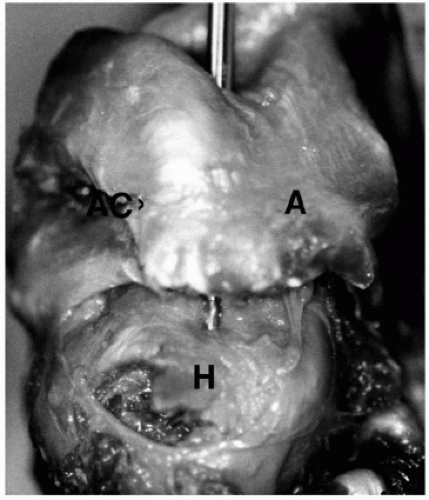

Arthroscopic repair of a massive cuff tear is unpredictable. Surgical visualization and mobilization determine whether a massive tear is repairable, partially repairable, or irreparable. A tear is not deemed irreparable until it is evaluated at the time of arthroscopy. Many tears that appear irreparable preoperatively can be mobilized by capsular techniques and interval slides,13 enabling a partial or complete repair of a once “irreparable” tear (Fig. 9-4). The authors do not treat any rotator cuff tears by open techniques.

If the tear is indeed irreparable, debride the bursal tissue and preserve the coracoacromial arch. Some surgeons prefer to make the undersurface of the acromion smooth by removing a large anterior spur so that the undersurface of the acromion is flatter, but the insertion of the coracoacromial ligament onto the undersurface of the acromion must be preserved. If the coracoacromial ligament is removed, the humeral head may “escape” anterior, leading to anterosuperior shoulder instability. This creates a disastrous complication, especially in the patient who can lift the arm overhead even though there is a massive rotator cuff tear. Partial repair of the rotator cuff tear—namely, the subscapularis or infraspinatus tendons while leaving a defect in the supraspinatus tendon—is helpful,18 improving pain and function by restoring the rotator cuff cable and force couples necessary for arm elevation.13

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

The surgeon must balance skill versus ego in arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. The surgeon must be in control of the operating theater. Detailed knowledge of the proper tools, suture management, and knot-tying techniques is essential. The skills required for the specific steps can be honed using the “Alex” shoulder model (Fig. 9-5). The surgeon must have not only a favorite plan, Plan A, but also a Plan B and even a Plan C. A surgeon learning arthroscopic rotator cuff repair can easily bail out of the arthroscopic procedure at any time and proceed to an open repair of the rotator cuff through a mini deltoid-splitting incision.

Control of Bleeding

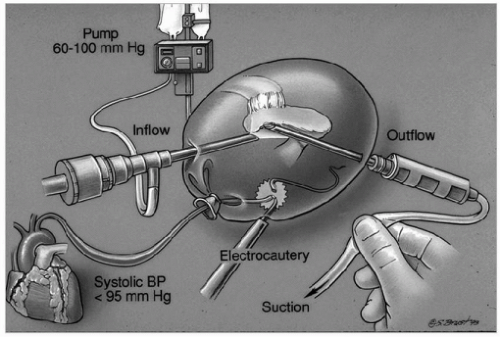

Controlling bleeding is essential for a good repair. Some tips for efficient control of bleeding include flowing fluid in through the arthroscope, controlling outflow through the shaver blades, and being aware of the nuances of an arthroscopic fluid management system (Fig. 9-6). The anesthesiologist lowers and safely monitors the systolic blood pressure in the range of 90 to 100 mmHg. Use electrocautery to stop any troublesome bleeding vessels. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and other drugs that can cause bleeding must be discontinued at least 7 days before surgery.

Patient Positioning

Arthroscopic cuff repair can be done in the seated position. The authors place the patient in the lateral decubitus position. Turn the operating table so that the anesthesiologist is at the foot (Figs. 9-7 and 9-8). Prepare and drape the shoulder after the arm is suspended with 10 to 15 lb of weight. Perform a glenohumeral arthroscopy in a systematic fashion

using a standard posterior portal and an anterior portal created with the Wissinger rod technique through the rotator interval. Treat any cartilage and labrum pathology. Examine the rotator cuff tear and evaluate the cuff footprint.

using a standard posterior portal and an anterior portal created with the Wissinger rod technique through the rotator interval. Treat any cartilage and labrum pathology. Examine the rotator cuff tear and evaluate the cuff footprint.

Portal Placement

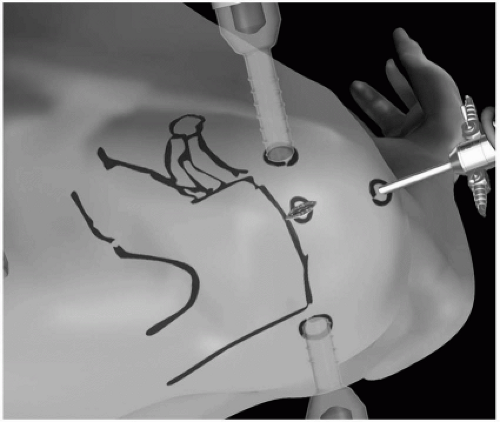

Create three portals for the rotator cuff repair. Enter the subacromial bursa from the posterior portal for initial viewing. Create the lateral portal three fingerbreadths lateral to the acromion (Fig. 9-9). Remove the bursa, debride the torn cuff, and abrade the bony footprint through this portal. Make the anterior subacromial portal by entering the bursa just lateral to the coracoacromial ligament. This enables the cannula to be easily moved but does not disrupt the coracoacromial arch. Excise bursa as necessary for visualization. Use electrocautery as necessary to control bleeding. Create additional portals as necessary. Insert suture anchors through a miniportal off the edge of the acromion. The additional superior portal behind the acromioclavicular joint can be used for a suture-retrieving device to pass sutures through the edge of a crescent-shaped tear.5

The authors prefer the lateral subacromial portal—the “50-yard line” view (see Fig. 9-9)—for optimal viewing of the rotator cuff. Place 7- to 8.5-mm plastic cannulas in the anterior and posterior portals for use in passing tools and suture. Move the tools, suture, and even the arthroscope as needed. Do not become limited to one portal.

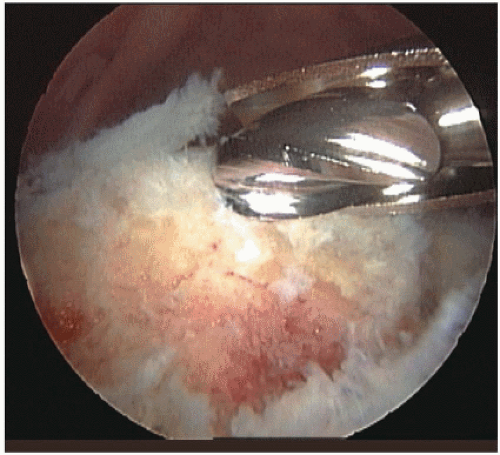

Preparing the Site and Beginning the Repair

Remove the bursa tissue as necessary for visualization of the cuff repair. Find a tissue plane that can see the extent of the cuff tear. Free up any adhesions between the cuff or bursa and the overlying acromion. Use a shaver-blade or high-speed burr to remove any remaining rotator cuff at the greater tuberosity insertion. Gently debride the surface of the bone to provide bleeding for repair of the cuff to bone (Fig. 9-10). Gently shave the edges or layers of the rotator cuff edges, but do not excise any significant pieces of the torn cuff that are mechanically sound.

Figure 9-9 The arthroscope is in lateral portal, providing the “50-yard-line” view. Note the anchor insertion portal adjacent to the acromion. |

Determine Tear Configuration

The next step involves determining the configuration and repairability of the cuff. Use probes or grasping forceps to assess how to repair the rotator cuff. Use grasping forceps in both hands while an assistant holds the arthroscope. First determine the feasibility of a repair and then, if feasible, the steps necessary to achieve it. Diagram the final repair on paper, even though changes may occur during the procedure.

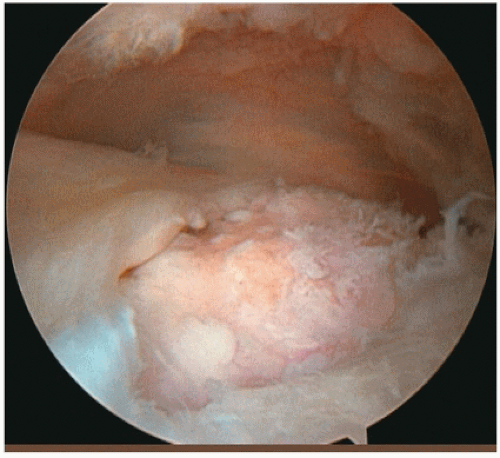

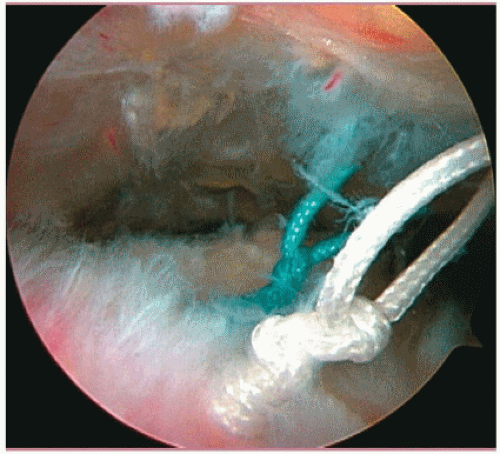

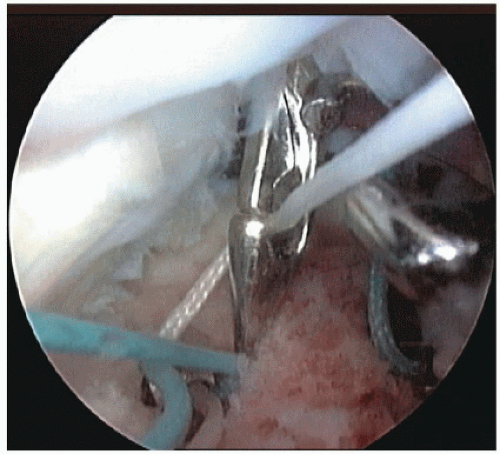

Rotator cuffs tear in a crescent-, L-, or U-shaped fashion. Crescent-shaped tears (Fig. 9-11) can be repaired directly to the bony footprint under minimal tension with doubleloaded suture anchors placed though a miniportal off the edge of the acromion (Fig. 9-12). The sutures can be passed though the free edge of the tear by means of an ArthroPierce (Smith & Nephew Endoscopy, Andover, MA) inserted superiorly behind the acromioclavicular joint from the supraclavicular fossa portal, while viewing from the lateral portal (Figs. 9-13 and 9-14). This allows a good bite of tissue. The ArthroPierce can also pass through the free edge of the tear from the posterior portal. Alternatively, the sutures can be passed with a suture-passing device (Fig. 9-15) from the lateral portal, viewing from the posterior portal. Other options include a curved CuffSew (Smith & Nephew Endoscopy),

device, a suture punch, a crescent hook, and other devices that shuttle suture through the tendon.

device, a suture punch, a crescent hook, and other devices that shuttle suture through the tendon.

L-shaped tears run parallel to the anterior edge of the supraspinatus, and U-shaped tears are located in the infraspinatus-supraspinatus interval; both tend to be highly mobile in the anterior to posterior direction. With L-shaped tears, the posterior leaf is more mobile than the anterior leaf (capsule in the rotator interval), whereas both leaves are mobile with U-shaped tears. Therefore, repair L-and U-shaped tears initially by a side-to-side margin convergence using a free suture, creating, in effect, a small crescent-shaped tear. Then attach the free edge of the tear to the bone using the suture anchor technique. Sometimes it becomes necessary to place the sutures through the torn cuff only after the suture anchors have been appropriately positioned in the bony footprint, because the footprint will

be covered during margin convergence, and access to it will be lost. Include any layering of the torn rotator cuff into the suturing technique, just as in open surgery.

be covered during margin convergence, and access to it will be lost. Include any layering of the torn rotator cuff into the suturing technique, just as in open surgery.

Figure 9-14 ArthroPierce from superior portal through the cuff retrieving suture.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|