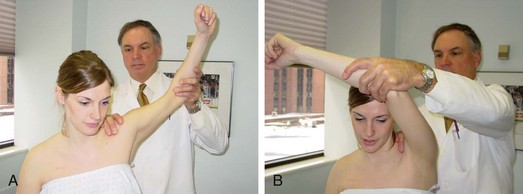

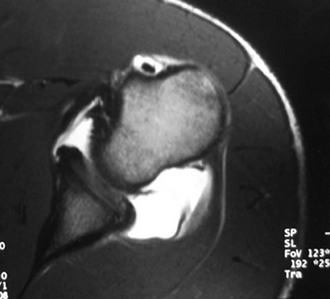

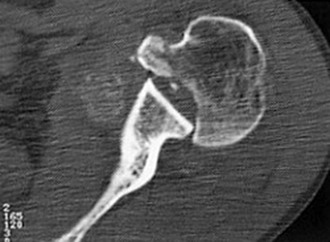

Chapter 9 Posterior instability, when compared with anterior instability of the shoulder, is relatively uncommon. Reports in the literature state that posterior shoulder instability represents approximately 2% to 10% of shoulder instability cases.1,4,16 Initial attempts to clarify the distinctions of posterior instability were made in 1952 when McLaughlin recognized that differences exist between “fixed and recurrent subluxations of the shoulder,” suggesting that the etiology and treatment of the two are distinctly different.4 More than 20 years later, Hawkins reiterated the difference between true dislocations and subluxations and noted that true recurrent posterior dislocations are rare compared with recurrent posterior subluxation (RPS) episodes.5 Since that time, additional knowledge has been gained regarding the differences between unidirectional versus multidirectional, traumatic versus atraumatic, acute versus chronic, and voluntary versus involuntary posterior instability. In many respects each of these may represent a distinct form of posterior instability with its own underlying predispositions, anatomic abnormalities, and treatment algorithms.6–8 Our collective understanding of posterior shoulder instability continues to evolve. Our understanding of the spectrum of posterior instability has evolved more recently through the study of shoulder injuries in athletes, patients with generalized ligamentous laxity, and patients with posttraumatic injuries. These athletes typically have posterior shoulder instability secondary to repetitive microtrauma, which can occur in multiple arm positions and under a variety of loading conditions. RPS has been observed in overhead throwers, baseball hitters, golfers, tennis players, butterfly and freestyle swimmers, paddling sport athletes, weightlifters, rugby players, and football lineman, among others.9,10 The more common cause of RPS is repetitive microtrauma, most commonly resulting from posterior capsular attenuation and posterior labral tears. Regardless of the type of athlete, patients with RPS often have somewhat ambiguous complaints of diffuse pain and shoulder fatigue without a distinct complaint of instability, often making it tricky to expose the underlying diagnosis and thus the associated pathology. Acute posterior dislocations typically occur as a result of a direct blow to the anterior shoulder or indirect forces that couple shoulder flexion, internal rotation, and adduction.8 The most common indirect causes are accidental electric shock and convulsive seizures, although these are relatively uncommon in the general population. However, recurrent or locked posterior shoulder dislocations from macrotrauma are exceedingly rare in the athletic population.4,5 The treating physician, because of incomplete radiographic studies and a failure to recognize the posterior shoulder prominence and mechanical block to external rotation, may overlook up to 80% of locked posterior dislocations. Additional pathologic conditions to look for include the following: To diagnose posterior instability, the clinician must take a thorough history and perform a thorough physical examination in addition to maintaining a high index of suspicion. A history of a posterior dislocation requiring formal reduction is more obvious; however patients with RPS may have more subtle findings. The majority of patients with RPS primarily report pain with specific activities, particularly in the provocative position (90 degrees of forward flexion, adduction, and internal rotation),8 more often than instability. Knowledge of the athlete’s sport, position, and training regimen is critical in deducing the pathogenesis and specific pathology associated with RPS. Pollock and Bigliani noted that two thirds of athletes who ultimately required surgery had presenting symptoms of difficulty using the shoulder outside of sports, particularly with arm above the horizontal.7 An inquiry should also be made regarding mechanical symptoms; one study found that 90% of patients with symptomatic RPS noted clicking or crepitation with motion.11 Often this crepitus can be reproduced during examination and is caused by discrete posterior capsulolabral pathology. • Inspection for skin dimpling, atrophy, and scapular motion • Active and passive range of motion • Palpation for tenderness (especially posterior glenohumeral joint) • Assessment for generalized ligamentous laxity (9-point Beighton scale) – Load and shift test for anterior and posterior translation (Fig. 9-1) – Sulcus sign (both in neutral and external rotation) for inferior translation – Sulcus sign graded as 3+ that remains 2+ in external rotation is pathognomonic for multidirectional instability (MDI) • Plain radiographs including an axillary view, anteroposterior view, and scapular-Y view – Reverse Hill-Sachs lesions (Fig. 9-4) of the humeral head – Glenoid pathology (retroversion, rim fractures, and hypoplasia) – Bony humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligaments (HAGL) • Magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA) – Capsule, biceps tendon, subscapularis integrity – Soft tissue reverse HAGL lesion – Demonstrate labral peel-back in the abduction and external rotation (ABER) position, consistent with posterosuperior labral tear (or type VIII superior labral anterior-posterior [SLAP] tear)13 Many patients with RPS can be managed successfully without surgery. Numerous authors have proposed a period of no less than 6 months of physical therapy before consideration of surgical treatment.5,14 Effective rehabilitation includes avoidance of aggravating activities, restoration of a full range of motion, and shoulder strengthening. Strengthening of the rotator cuff, posterior deltoid, and periscapular musculature is critical. The premise of such directed physical therapy is to enable the dynamic muscular stabilizers to offset the deficient static capsulolabral restraints. Nearly 70% of patients improve after an appropriate rehabilitation protocol. The recurrent subluxation, however, is generally not eliminated, but the functional disability is diminished enough that it does not prevent activities.15 If the disability fails to improve with an extended 6-month period of directed rehabilitation, or in select cases of posterior instability resulting from a macrotraumatic event, surgical intervention should be considered. Patients failing extensive physical therapy protocols should receive surgical consideration. Interval plication and suture capsulorrhaphy techniques have improved arthroscopic results, making them comparable to open procedures.10,16–18 Advantages of arthroscopic techniques over traditional open techniques include less disruption of normal shoulder anatomy; better visualization of intra-articular landmarks; the ability to perform concomitant SLAP repairs, capsular tear or rent repairs, and anterior and posterior stabilization procedures; and complete visualization of both the intra-articular and subacromial spaces. The surgeon’s transition from open to arthroscopic techniques can be difficult. Arthroscopic techniques require the surgeon to be familiar with anchor placement, suture management, and arthroscopic knot tying. A thorough understanding of arthroscopic anatomy is vital to the success of arthroscopic stabilization procedures. Open techniques require larger incisions, a deltoid-splitting approach, and either splitting the bipennate infraspinatus muscle or developing the interval between the infraspinatus and the teres minor. On the other hand, open techniques allow complete visualization of the posterior capsule and offer the opportunity to perform a reliable capsular shift and/or posterior labral repair. Indications for arthroscopic posterior stabilizations include patients with continued disabling isolated RPS after a rehabilitation program, RPS with a posterior labral tear, MDI with a primary posterior component, and voluntary positional posterior instability. Relative indications include patients with an antecedent macrotraumatic injury. Contraindications include patients not having completed a reasonable rehabilitation program, a surgeon preference for traditional open techniques, a large engaging reverse Hill-Sachs lesion requiring subscapularis transfer or an osteochondral allograft, a large reverse bony Bankart lesion, patients with muscular voluntary instability and underlying psychogenic disorders, and patients unable or unwilling to comply with postoperative limitations. Relative contraindications may include chronic instability resulting in compromised capsulolabral tissue, and patients who have undergone previous open surgery. Because successful results have been achieved with arthroscopic treatment of posterior labral tears in contact athletes,10,19 arthroscopic reconstruction is not contraindicated in this population.9 As arthroscopic techniques continue to evolve, the surgical indications will likely broaden.

Arthroscopic Repair of Posterior Shoulder Instability

Pathoanatomy

Diagnosis

Clinical Examination

Radiographs

Treatment

Indications and Contraindications

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Musculoskeletal Key

Fastest Musculoskeletal Insight Engine