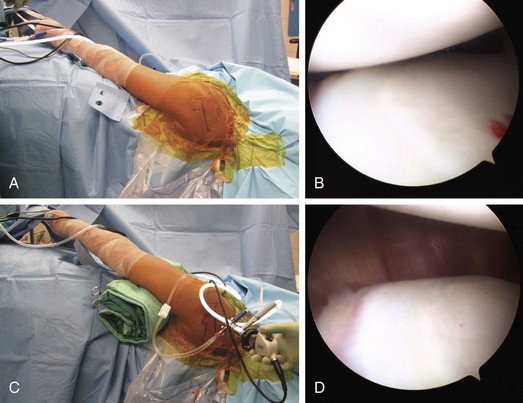

Chapter 10 Multidirectional instability, first described by Neer and colleagues in 1980,1 is currently defined as instability in at least two of the following directions: anterior, posterior, and inferior. Most cases of instability are thought to be a result of nontraumatic processes—for example, microtrauma caused by repetitive overhead actions such as those common in swimmers and throwers. More recently, though, the disease paradigm has expanded to encompass Pagnani and Warren’s circle theory, which states that an anterior dislocation results in the stretching or tearing of both the anterior and posterior capsular ligaments.2 The stretching of both ligaments then creates variable degrees of multidirectional symptoms in patients with purely anterior dislocations. This has led to the need for posterior repair with anterior dislocations. Clinical experiences have shown that neglecting the posterior band in these patients leaves them still experiencing instability. Biologically, several pathologic processes are thought to be responsible for multidirectional instability: capsular laxity, labral detachment, rotator interval defects, and changes in quality and type of collagen.3 Typically, multidirectional instability is a result of microtrauma caused by repetitive overhead actions that lead to global capsular laxity. Less commonly, a traumatic shoulder dislocation may be the inciting event. Additional causes include generalized ligamentous laxity or Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, a disease that causes defects in collagen synthesis. A typical patient is young, is active, and has shoulder pain that may be accompanied by popping, clicking, and grinding in addition to reports of shoulder shifting, instability while sleeping, pain or numbness while carrying heavy objects, difficultly with overhead activity, and feelings of instability during pushups or bench-presses. Often, he or she is no longer able to participate in sports and may report prior physical therapy that was unsuccessful.4 A subset of patients also report being able to voluntarily dislocate the shoulder. With these individuals, it is imperative to distinguish between those who are able to voluntarily dislocate and those who are dislocating for secondary gain. The former can be a challenging candidate for surgery and scapular retraining in addition to needing evaluation for potential psychological or psychosocial issues, whereas the latter make poor surgical candidates. Throughout the examination, it is important to ask patients to report when they begin to feel instability as well as to note any apprehension, as this will help give an accurate impression of the severity and direction of instability. A complete examination will include inspection for atrophy, scapulothoracic and glenohumeral active and passive range-of-motion testing, strength testing, palpation for tenderness, evaluation of ligamentous laxity, and evaluation for impingement and instability. Anterior instability is best evaluated with the anterior drawer, load and shift, anterior release, and anterior relocation and apprehension tests, whereas posterior instability is evaluated with the posterior drawer, load and shift, and stress and jerk tests. The hallmark finding in multidirectional instability is a positive sulcus sign in neutral rotation (Fig. 10-1). A sulcus sign that remains positive with 30 degrees of external rotation indicates likely rotator interval pathology. The O’Brien, Kim, circumduction, and speed tests are also performed. Examination under anesthesia may be needed to confirm clinical findings before progressing to surgery. In many patients with atraumatic multidirectional instability, dynamic neuromuscular control of glenohumeral stability is lost. Before surgical treatment is considered, patients should begin a physical therapy regimen (conservative treatment) that focuses on strengthening rotator cuff muscles and scapular stabilizers as well as improving proprioception. If instability persists after physical therapy, individuals should progress to surgery, especially if there is difficulty with day-to-day activities. Considering that after an acute shoulder dislocation the risk of recurrence can be as high as 80% in young athletic individuals, surgical intervention is highly warranted once physical therapy has failed.5 One complication that requires extensive discussion is the potential for decreased range of motion after surgery. Although this may be acceptable to older or less active patients, athletes, especially throwers and gymnasts, may have much lower tolerances for loss of motion. Arthroscopic treatment of athletes with multidirectional instability has been successful, with 91% of athletes reporting full or satisfactory range of motion after surgery and 86% returning to their sport with little or no limitation.6 In addition, although athletes should always participate in a physical therapy program before progressing to surgery, surgical options may be presented earlier if the individual is not making significant progress and is losing valuable playing time. Ideally, physical therapy would begin early in the season to midseason followed by end-of-season surgery, allowing postoperative rehabilitation to take place during the off-season. Surgical planning continues with the examination under anesthesia and diagnostic arthroscopy. This may alter the plan to include rotator interval closure, anterior posterior labral repair, superior labral anterior-posterior repair, and biceps tenodesis or tenotomy. Because the multipleated plication technique is as effective in decreasing capsular volume as an open capsular shift, conversion to an open procedure should not be needed.7 Anesthesia, Examination, and Positioning The procedure is performed with an interscalene block for postoperative pain control and general endotracheal anesthesia with administration of prophylactic antibiotics. The examination under anesthesia is performed on a firm surface with the scapula relatively fixed and the humeral head free to rotate. The degree and direction of instability should be noted. A load and shift test is performed with the arm held in 90 degrees of abduction and neutral rotation while an anterior or posterior force is applied in an attempt to translate the humeral head over the anterior or posterior glenoid. A sulcus sign test is also needed. The arm is adducted and placed in neutral rotation and pulled inferiorly (see Fig. 10-1A). The test result is positive if a dimple appears in the subacromial region as the humeral head translates inferiorly (see Fig. 10-1B). Testing should be done on both the affected and unaffected shoulder.8 The table should be in a slight reverse Trendelenburg position with the patient in the lateral decubitus position with the operative shoulder facing superiorly. This position offers excellent views of the inferior and posterior capsular regions. Three layers of tape are placed over the greater trochanter, stomach, and chest area to secure the patient. An inflatable beanbag is used for stabilization. Pillows should be placed underneath the down leg and between the legs to keep pressure off the peroneal nerves. The operative adducted arm is then propped up with an axillary bump, which allows for better views of the glenohumeral joint (Fig. 10-2). The arm is then prepared and draped in standard sterile fashion.

Arthroscopic Repair of Multidirectional Instability of the Shoulder

Preoperative Considerations

Physical Examination

Indications and Contraindications

Surgical Planning

Surgical Technique

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Arthroscopic Repair of Multidirectional Instability of the Shoulder