CHAPTER 22 Arthroscopic Microfracture and Chondroplasty

Imaging and diagnostic studies

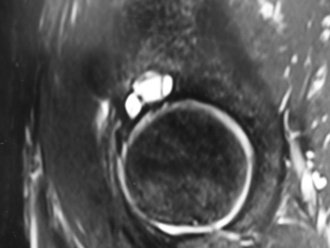

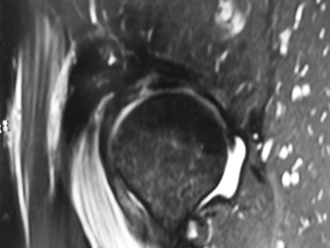

Magnetic resonance imaging may be helpful to obtain a cause of the pain; however, many authors have noted that articular cartilage defects are frequently not clearly identified by the imaging sequences and resolutions that are often used (Keeney CORR 2004). Secondary signs of articular cartilage damage may be identified, such as subchondral bony cysts, bone edema (Figure 22-1), and joint effusions. High-resolution images may demonstrate distinct defects (Figure 22-2), articular cartilage thinning, or heterogeneity of the articular cartilage signal (Figure 22-3). The use of a surface coil with high-resolution, cartilage-sensitive images in the axial, coronal, and sagittal planes may provide a higher spatial resolution that could be helpful for diagnosis. Magnetic resonance arthrography improves the ability to evaluate the articular surface, but current techniques lack reliable sensitivity. In the future, the use of delayed gadolinium-enhanced MRI of cartilage (dGEMRIC) may provide additional information about the proteoglycan content of the articular cartilage.

Figure 22–2 Magnetic resonance image of a 16-year-old football player with a focal chondral defect in the acetabulum.

Surgical technique

A spinal needle is then placed into the hip joint, and the stylet is removed; this breaks the vacuum seal and decreases the force needed to distract the joint. If necessary, the needle should be repositioned to avoid the labrum. This initial portal should be placed so that the tip of the needle enters the fovea of the acetabulum; this helps to ensure the good visualization of the joint. After the appropriate placement of the initial spinal needle and the guidewire, portal placement with the use of cannulated trocars can be performed to allow for access to the joint for visualization and instrumentation. A thorough diagnostic examination of the hip should occur, and this should involve the use of multiple portals. In some cases, defects on the femoral head are relatively medial (Figure 22-4), and careful instrument placement (Figure 22-5) is necessary to identify and treat defects (Figure 22-6, A and B).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree