Arthroscopic Management of the Stiff Elbow

Andrew Tarleton

Michael J. O’Brien

Felix H. Savoie III

INTRODUCTION

The elbow’s primary function is to position the hand in space. The stiff elbow, therefore, is fraught with the morbidity of functional disability. It is a frequently encountered problem for the orthopaedic surgeon in the management of elbow pathology. Trauma is the most common etiology. The causes are generally divided into intrinsic and extrinsic factors. “Intrinsic factors” refers to any cause within the joint itself such as arthritis, osteophytosis, capsular contracture and adhesions, or joint incongruity. “Extrinsic factors” include muscle contractions, heterotopic ossification, and skin contractures (1). Stiffness can also result secondary to varied conditions such as brain or spinal cord injuries, burns, or paralytic deformities (2). Prolonged joint immobilization leads to progressive contracture of the capsule and pericapsular tissues, intra-articular fibrofatty connective tissue, and articular cartilage fibrillation (3). The preferred treatment is as varied as the etiology and includes both open and arthroscopic management. For severe injuries that involve the articular surface, interposition arthroplasty has been shown to be effective but is a very technically demanding procedure. Joint replacement arthroplasty generally is not considered as a treatment for stiffness unless the patient is older than 65 years (4).

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

The elbow is a complex joint that acts as a link for the body to adjust the hand in space. The distal humerus is anteriorly angulated 30 degrees, is internally rotated 5 to 7 degrees, and is in 6 to 8 degrees of valgus (5). Secondary to the complex anatomic interactions at the elbow joint, even a relatively minor injury can result in significant stiffness (3). Normal motion of the elbow was defined by Boone as 0 to 145 degrees flexion and 86 to 93 degrees in supination (6). Based on Morrey’s work, motion consisting of flexion from 30 to 130 degrees and 50 degrees each of pronation and supination is thought to be sufficient to accomplish most activities of daily living (7). Motion loss usually consists of loss of extension, but loss of flexion is also common (4).

Nonsurgical treatment consisting of physical therapy and splinting for loss of motion is generally attempted for at least 3 months before surgery is considered. Use of a custom-fit turnbuckle orthotic has been shown to increase the overall arc of flexion by 43 degrees (8). Bupivacaine hydrochloride with or without steroid injections, protected range of motion using a double-hinged elbow brace, and physical therapy may prove efficacious (3). Manipulation under general anesthesia has also been reported with favorable results (9).

The primary surgical indication would be loss of the functional range of motion of the elbow that fails conservative treatment. There are certain vocational and personal needs whereby individuals with an apparently adequate arc of motion may request additional motion. The justification of indication for surgical intervention is thus highly individualized regarding the patient’s needs and expectations (4). Based on the above data concerning range of motion, surgical release has been generally indicated for patients with flexion contractures greater than 30 degrees. There is also a subpopulation, such as high-level athletes, in whom loss of terminal extension is unacceptable and impairing, thus

expanding the indications to include functional impairment secondary to contracture (10). Open surgical management may increase scar production around the elbow, thereby contributing to contracture, prompting one to consider arthroscopic management. Advantages of an arthroscopic approach include minimal incision size, decreased blood loss, decreased postoperative pain, better visualization of the articular surface, and decreased soft tissue dissection, theoretically leading to easier rehab (1,11).

expanding the indications to include functional impairment secondary to contracture (10). Open surgical management may increase scar production around the elbow, thereby contributing to contracture, prompting one to consider arthroscopic management. Advantages of an arthroscopic approach include minimal incision size, decreased blood loss, decreased postoperative pain, better visualization of the articular surface, and decreased soft tissue dissection, theoretically leading to easier rehab (1,11).

Contraindications for elbow arthroscopy would include bony ankylosis or significant heterotopic ossification around one of the nerves preventing the safe establishment of arthroscopic portals (12). Heterotopic ossification is extracapsular and often closely located to neurologic structures, particularly the ulnar nerve (13). Prior ulnar nerve transposition can be considered a relative contraindication secondary to increased risk of iatrogenic nerve injury. Though not contraindications, disadvantages include the need for advanced arthroscopic skills and the risk of nerve injury (1). A relatively small incision over the ulnar and/or radial nerves to allow their localization and protection is often a useful adjunct to the management of the stiff elbow.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

A thorough history and physical are the pillars on which the treatment is going to be directed. Specific elements of the history that need clarification include the following: What is the mechanism (if posttraumatic), what is the timeline, previous procedures (for which one may want to acquire the operative reports), including previous ulnar nerve transposition, previous conservative treatment, and a careful neurovascular exam with documentation of preexisting signs of neural irritation or deficits. In some instances, patients may not notice subtle changes in ulnar innervated musculatures secondary to a greater focus on the impaired function of the elbow (9). One element of the history that deserves special attention is pain. Posttraumatic stiffness is generally not overly painful. Individuals who have pain with motion may have a problem with the articular surface, meaning an intrinsic component, and thus may be in need of a resurfacing or an interposition type of intervention (4). Previous physical therapy and the use of any splinting—either short or long term—should be documented (3).

Physical examination must include careful evaluation of the soft tissues around the elbow looking for scars, burns, or soft tissue deficit. A goniometer is the most accurate way to monitor the range of motion of the elbow. Radiographs consisting of anteroposterior, lateral, and oblique views of the elbow (Fig. 15-1) are routinely obtained to assist in identifying potential sources of loss of motion. In addition to this routine imaging, advanced imaging consisting of computed tomography with three dimensional reconstructions can be obtained for further characterization of osseous anatomy. Magnetic resonance imaging may also be employed to evaluate the ligamentous structures about the elbow and to identify cartilaginous loose bodies.

Conservative treatment with physical therapy and splinting is generally the mainstay of treatment for mild contractures. Caution always should be observed during therapy to prevent additional capsular damage and worsening of the arthrofibrotic condition (3). A variety of open techniques have historically been shown to be effective in treating the stiff elbow. Arthroscopy offers the advantages of a limited soft tissue dissection and skin incision, which should lower the risk of subsequent scarring and also allow less impedance to postoperative physical therapy. Various techniques used in the past such as open or mini-open: capsulectomy, extensive capsular release, capsular release with biceps tendon lengthening, brachialis myotomy, and release of the more anterior fibers of the collateral ligaments have paved the way for arthroscopic management (14).

PREOPERATIVE COUNSELING

Management of the arthrofibrotic elbow is one of the more complex procedures a patient may undergo. The risk of potential complications, including recurrence and nerve injury, is quite real, and most likely underreported. The surgeon and patient willing to undertake this treatment must be aware of the real possibility of significant complications associated with treatment. Despite the surgeon’s best intentions, infection, stiffness, pain, and transient and permanent neuropathy should be considered likely to occur. The chance of these complications must be understood and accepted by both the treating physician and the patient before surgery is considered.

SURGERY

Equipment

If an arthroscopic pump is used, we suggest very low pressure and flow, or the use of gravity inflow— in order to avoid overdistension and edema. Edema can occur and progress rapidly during elbow arthroscopy, limiting visibility and the ability to work safely. Equipment needed includes a 4.0 arthroscope, an interchangeable low-flow cannula system, and 3.5-mm or 4.0-mm resectors. Other standard arthroscopy equipment includes a shaver, cautery devices, graspers, burrs, punches, and probes (15).

Prior to Incision

Positioning is accomplished in either the prone or the lateral decubitus position. The shoulder is flexed to 90 degrees and abducted. This positioning has the advantage of allowing easy manipulation of the extremity, without the need for a traction device (Fig. 15-2). Investigation of range of motion

with the patient under anesthesia is performed. A nonsterile tourniquet is placed on the upper arm to limit bleeding, and the arm is placed into an arm holder. Sterile prep and drape are performed in the usual fashion. Anesthesia can be either regional or general, with general anesthesia having the advantage of allowing immediate neurologic exam after surgery. Also the use of general anesthesia allows full muscle relaxation and permits the patient to be positioned in either a prone or a lateral position, which may not be tolerated in an awake patient (11).

with the patient under anesthesia is performed. A nonsterile tourniquet is placed on the upper arm to limit bleeding, and the arm is placed into an arm holder. Sterile prep and drape are performed in the usual fashion. Anesthesia can be either regional or general, with general anesthesia having the advantage of allowing immediate neurologic exam after surgery. Also the use of general anesthesia allows full muscle relaxation and permits the patient to be positioned in either a prone or a lateral position, which may not be tolerated in an awake patient (11).

Prior to incision, the course of the ulnar nerve is identified subcutaneously (Fig. 15-3). Once the nerve is identified, it is checked to make sure that it does not subluxate from the cubital tunnel (11).

If it cannot be traced out, that necessitates exploration for identification. Bony landmarks are demarcated prior to incision as they may be more difficult to discern after joint distension. These pertinent anatomic landmarks are identified not just for the ulnar nerve, but for all structures around the elbow—and will be used to allow for safe portal placement. Elbow arthroscopy is a sensitive procedure secondary to the proximity of neurovascular structures and the constraint of the joint in a fully mobile joint, safety concerns are heightening in the stiff elbow. If the elbow is fixed at 90 degrees of flexion or if there is significant scarring around the ulnar nerve, we recommend the ulnar nerve be explored, decompressed, and tagged with a vessel loop as the first part of the surgery prior to initiation of arthroscopy of the elbow (1).

Portals

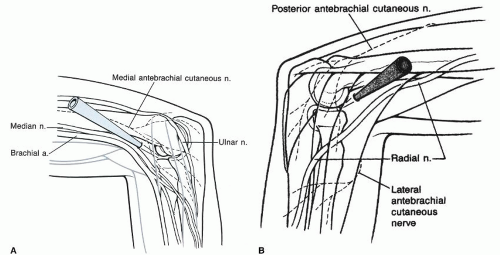

Proper portal placement could arguably be the most important part of the procedure as it affords entrance to the joint and prevents neurovascular injury. A thorough knowledge of the three-dimensional anatomy of the elbow is essential (Fig. 15-4). Portals should be created with the elbow flexed to 90 degrees (16). It should be noted that capsular contracture leads to substantial loss of intra-articular volume capacity of the elbow joint—with a mean decrease from 23 mL in normal elbows to 6 mL in the stiff elbow (9).

As opposed to a straight posterior portal, the portal for insufflation is generally via a soft-spot/direct lateral portal with the needle crossing the joint to place the fluid in the anterior compartment; this is due to the fact that the contracture can limit the flow of fluid from the medial and lateral gutters to the anterior elbow joint. This portal is created between the olecranon tip, radial head, and lateral epicondyle.

The first working portal established is the proximal anteromedial described by Peohling. Protection of the ulnar nerve is paramount in establishing the medial portal in a proximal-anterior position. The entry site is placed 2 cm proximal to the medial epicondyle and at least 2 cm anterior to the intermuscular septum, aiming at the medial aspect of the trochlea to enter the joint. When the elbow is flexed 90 degrees, the portal entry site is 2 mm from the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve (17). The scalpel is used to incise the skin only. In the event that a prior ulnar nerve transposition has be performed, a larger incision is recommended and followed by blunt dissection in order to visualize a safe path to the portal entry site free from the ulnar nerve.

Next, the proximal anterolateral portal is created, either by direct visualization via an outside-in technique or in severe cases via a switching stick and inside-out technique. In the more severe cases, the inside-out technique may allow a better initial working space. Using proximal portals to begin the procedure adds an anatomic protective factor to assist in the prevention of inadvertent neurologic injury. After the portal is established, visualization often can be quickly improved by sweeping the trocar superiorly along the humerus, allowing the brachialis muscle to displace anteriorly (Fig. 15-5). Anteromedial and anterolateral portals may be used to place a switching stick or freer to use as a retractor of the soft tissues to protect the median nerve and brachial artery (medial-central) or

posterior interosseous nerve (laterally) (14). In the event of significant bony deformity on the medial side of the joint, the proximal anterolateral portal may have to be created first. It is located roughly 2 cm proximal to the lateral epicondyle and 2 cm anterior to the lateral intermuscular septum.

posterior interosseous nerve (laterally) (14). In the event of significant bony deformity on the medial side of the joint, the proximal anterolateral portal may have to be created first. It is located roughly 2 cm proximal to the lateral epicondyle and 2 cm anterior to the lateral intermuscular septum.

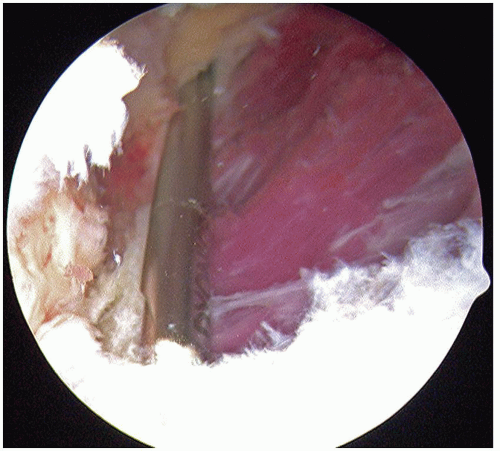

FIGURE 15-5 Significant synovitis and fraying of the joint capsule is visualized from the anteromedial portal. The distal anterior humerus is at the superior aspect of the field. |

Arthroscopic Technique: Anterior Elbow

Once in the joint with both portals, one will be able to visualize the anterior elbow and inspect the contracture (Fig. 15-6). The anterior capsule is taut in extension, and the posterior capsule is taut in flexion (3). Resection of the anterior capsule from the nonarticular portion of the humerus is begun medially with visualization from the lateral portal. The median nerve, radial nerve, and brachial artery are in jeopardy when resecting the anterior capsule, and the crucial element to not injuring these structures is to stay posterior to the brachialis muscle. After visualization of the brachialis, retractors are used to hold it away from the capsule, thus protecting the neurovascular structures (Fig. 15-7

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree