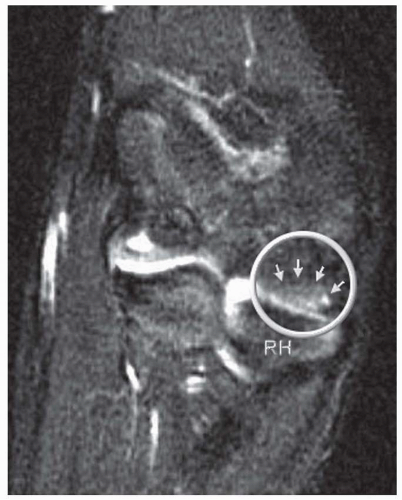

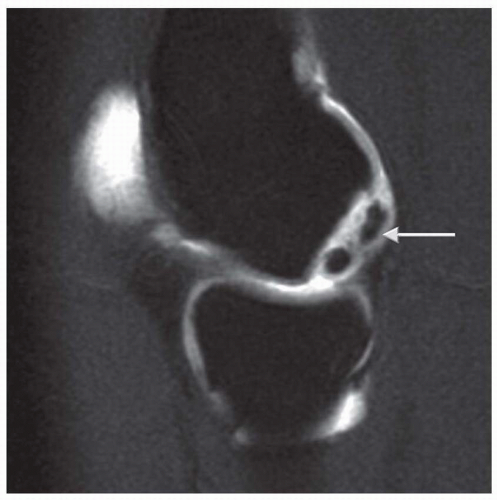

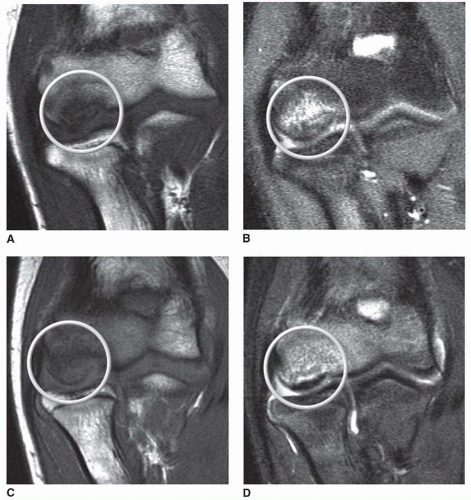

partially detached piece from subchondral bone (Fig. 4.6). Peiss et al. (19). felt that fragment enhancement (seen in Fig. 4.7B) (as opposed to the perifragment enhancement seen in Fig. 4.6) denotes viability and may be a reasonable indication for nonoperative treatment. They also suggested that enhancement of the fragment-subchondral bone interface is caused by vascular granulation tissue, indicating instability and requiring operative intervention. Of note, it is critically important to distinguish “pseudolesions,” appearing on the posteroinferior

junction of the articular and nonarticular portions of the capitellum, from OCD which almost always presents on the anterolateral aspect. In addition, whether or not the capitellar physis is open or closed should be noted.

FIGURE 4.5 AP radiograph at 45 degrees flexion. OCD lesion (circle) is seen more clearly with elbow flexed to 45 degrees. |

TABLE 4.1 Classification and Treatment of Capitellar Osteochondritis Dissecans Lesions | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree