CHAPTER 14 Arthroscopic Labral Repair

Diagnosis of labral tears of the hip

The clinical presentation of patients with a tear of the labrum is variable, and, as a result, the diagnosis is often missed initially. Burnett and colleagues reported about a series of 66 patients in whom the diagnosis of a labral tear had been made by arthroscopy. In this series, the mean time from the onset of symptoms to diagnosis was 21 months. An average of 3.3 health care providers had seen each patient before the diagnosis of a labral tear was made. Groin pain was the most common complaint (92%), with the onset of symptoms most often being insidious. A positive “impingement sign” occurred in 95% of patients in this series; this sign consists of groin pain with flexion, adduction, and internal rotation of the symptomatic hip (Figure 14-1). Therefore, in young, active patients who present with complaints of groin pain, with or without a history of trauma, the diagnosis of a labral tear of the hip should be suspected and investigated further.

Surgical technique

Technique for Arthroscopic Labral Debridement

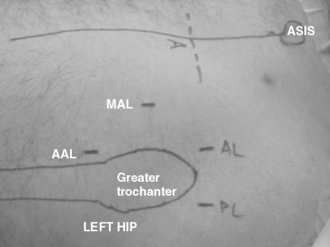

The procedure can be performed with the patient in either the supine or lateral position, depending on the level of comfort of the surgeon. The procedure should employ both a 30-degree and a 70-degree arthroscope for a thorough assessment of both the labrum and associated pathology. Modified arthroscopic flexible instruments, extended shavers, and hip-specific instrumentation should be available to improve access to all areas of the hip joint. In addition, the positioning of instruments should be done in the proper portals, with consideration for the anatomic structures near the hip joint (Figure 14-2).

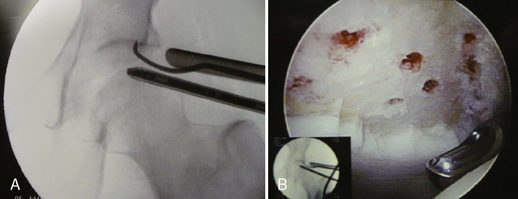

Adjacent cartilage damage should be searched for and thoroughly addressed. Superficial lesions can be gently debrided with mechanical shavers and perhaps stabilized with the use of radiofrequency probes. Grade IV Outerbridge lesions should be managed with a thorough debridement down to a bleeding bed and by preparation with microfracture awls (Figure 14-3).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree