CHAPTER 17 Arthroscopic Hip “Rotator Cuff Repair” of Gluteus Medius Tendon Avulsions

Introduction

Hip arthroscopy has recently been expanded to allow for the visualization and treatment of extra-articular pathology, specifically in the peritrochanteric compartment. Disorders in this compartment include external coxa saltans or snapping hip, trochanteric bursitis, and gluteus medius and gluteus minimus tears (Tables 17-1, 17-2, and 17-3). These pathologies, which were underappreciated before hip arthroscopy, have now been identified as significant causes of lateral hip pain. The previous treatment of these disorders with conservative modalities or open surgery has had varied efficacy, and it has been associated with significant postoperative morbidity. Conservative treatment is often the preferred treatment modality and includes corticosteroid and anesthetic injections in combination with a structured physical therapy regimen. Patients for whom conservative treatment is ineffective have previously required open surgery.

Table 17–1 External Coxa Saltans

| Treatment | Response | |

|---|---|---|

| Conservative | Rest, activity modification, stretching, corticosteroid injection, physical therapy | Varied |

| Open | Excision of ellipsoid portion of iliotibial band and trochanteric bursa | 80% improvement or full symptomatic relief |

| Arthroscopic | Transverse step cuts in the fascia and one longitudinal fascial incision | 88% with full symptomatic relief |

| Iliotibial band release (Z-plasty) | 95% full symptomatic relief |

Table 17–2 Trochanteric Bursitis

| Treatment | Response | |

|---|---|---|

| Conservative | Local corticosteroid and anesthetic injection with physical therapy | 66% excellent response and 33% improved symptoms |

| Open | Trochanteric reduction osteotomy | 50% excellent, 42% great, 8% fair improvement |

| Arthroscopic | Endoscopic bursectomy | Significant improvement in Harris Hip Score, visual analog scale results, and SF-36 score |

Table 17–3 Gluteus Medius and Minimus Tears

| Treatment | Response | |

|---|---|---|

| Conservative | Local corticosteroid and anesthetic injection with physical therapy | Up to 90% pain relief |

| Open | Tendon repair | No clinical data |

| Arthroscopic | Debridement of calcification and degenerated tendon | 100% asymptomatic |

| Tendon repair | 100% asymptomatic; 9 out of 10, full strength recovery |

Indications

Generally asymptomatic or can be treated conservatively with rest, activity modification, stretching, corticosteroid injections, and physical therapy

Generally asymptomatic or can be treated conservatively with rest, activity modification, stretching, corticosteroid injections, and physical therapy Conservative treatment with local corticosteroid and anesthetic preparation injections in combination with physical therapy as the mainstay of diagnosis and treatment

Conservative treatment with local corticosteroid and anesthetic preparation injections in combination with physical therapy as the mainstay of diagnosis and treatmentImaging and diagnostic studies

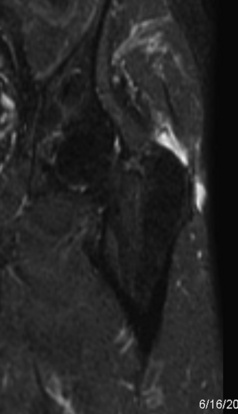

All patients who present with hip pain are evaluated with an anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis as well as a Dunn lateral radiograph (90 degrees of hip flexion, 20 degrees of abduction, and the beam centered on and perpendicular to the hip) to assess for avulsions of the greater trochanter, cam and pincer lesions, loss of joint space, crossover sign, acetabular dysplasia, and sacroiliac joint pathology. Magnetic resonance imaging provides the most information about the soft tissues that surround the hip (Figure 17-1). Every magnetic resonance imaging study of the hip should include a screening examination of the whole pelvis that is acquired with use of coronal inversion recovery and axial proton-density sequences. Detailed hip imaging is obtained with use of a surface coil over the hip joint, with high-resolution, cartilage-sensitive images acquired in three planes (sagittal, coronal, and oblique axial) with use of a fast-spin-echo pulse sequence and an intermediate echo time. Other alternatives include the use of magnetic resonance arthrography of the hip for the evaluation of hip pathology. Ultrasound is used most commonly to confirm the placement of injections into the trochanteric space for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. Dynamic ultrasound has also been described to evaluate external coxa saltans; it provides real-time images of the sudden abnormal displacement of the iliotibial band or the gluteus maximus muscle overlying the greater trochanter as a painful snap during hip motion. In addition, sonography can identify gluteus medius and gluteus minimus tendinopathy and provide information about the severity of the disease.

Surgical technique

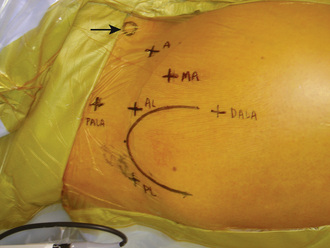

The importance of proper portal placement is critical during hip arthroscopy. For arthroscopy of the peritrochanteric space, a technique has been described that involves the use of both traditional and unique portals (Figure 17-2). The technique begins with the accurate identification of the trochanter and the marking of the arthroscopic portals. The procedure begins with routine central compartment hip arthroscopy to rule out associated intra-articular pathologies. Although intra-articular pathologies typically result in primary anterior or groin symptoms, it is also possible for these pathologies to result in primary lateral-sided hip pain. Central compartment arthroscopy is performed in all cases of peritrochanteric space endoscopy to document and treat any associated labral or chondral pathology that may coexist with the lateral-based pathology. The anterolateral portal is first established with the use of the standard Seldinger technique of a cannulated trochar over a guidewire, which is performed with the aid of fluoroscopy. To minimize trauma to the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, a mid-anterior portal is then established. This portal is made slightly more lateral and distal than the traditional anterior portal. The portal is critical to get into the peritrochanteric space, because it is the initial primary viewing portal. Thus, fluoroscopy is used to assist with the optimal placement of the mid-anterior portal over the lateral prominence of the greater trochanter. Before entry into the peritrochanteric space and after the completion of the central compartment evaluation, the peripheral compartment should be entered if there is any concern about peripheral compartment pathology.

The first structure to be visualized is the gluteus maximus tendon inserting on the femur just below the vastus lateralis (Figure 17-3). This structure is a reproducible landmark that provides good orientation within the space. It is typically unnecessary to work distal to the gluteus maximus tendon, and one should avoid exploration posterior to the tendon, because the sciatic nerve lies within close proximity (i.e., 2 cm to 4 cm). The camera light source is then directed to the lateral aspect of the femur, where the longitudinal fibers of the vastus lateralis can be visualized and followed proximally to the vastus ridge. The insertion and muscle belly of the gluteus medius are located proximal to this, whereas the gluteus minimus is located more anteriorly and is mostly covered. Finally, the iliotibial band is identified with the camera looking proximally and laterally.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree