Arthroscopic Chondroplasty and/or Debridement

Douglas W. Jackson

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

Chondroplasty is defined as the “surgical shaping of cartilage.” This shaping includes contouring and removing devitalized or detached cartilage fragments. The debridement of loose or fragmented articular cartilage may relieve mechanical symptoms associated with the diseased articular surfaces.

Chondroplasty of the knee is usually always part of an overall debridement procedure, and at the same time is an associated joint lavage and irrigation. This washout removes small particulate debris and bioactive molecules that may include inflammatory mediators and enzymes. Although the natural

history of the arthritic process in the knee joint is probably unaffected by arthroscopic chondroplasty, debridement, and lavage, in selected patients the procedure may reduce or eliminate certain mechanical symptoms.

history of the arthritic process in the knee joint is probably unaffected by arthroscopic chondroplasty, debridement, and lavage, in selected patients the procedure may reduce or eliminate certain mechanical symptoms.

A definition for arthroscopic debridement of the knee when used in the treatment of degenerative articular cartilage disease (degenerative arthritis) has not been defined in the literature. Therapeutic arthroscopic techniques for knee joint osteoarthritis include debridement and/or chondroplasty, partial meniscectomy, osteophyte excision, joint lavage, and loose-body removal. At the time of the arthroscopic assessment, in addition to a chondroplasty and debridement of the articular surfaces, the surgeon may also address exposed subchondral bone.

Several of these associated or concomitantly performed procedures are described in other chapters in this book, including the microfracture technique to stimulate localized repair over the exposed boney surface (Chapter 27), chondrocyte transplantation (Chapter 29), osteochondral autografts (Chapter 28), osteochondral allografts (Chapter 33) and associated osteotomy (Chapters 24, 30, and 31).

The indications for considering arthroscopic chondroplasty and debridement are primarily for mechanical symptoms in the knee that are felt to be secondary to articular cartilage fragmentation and loosening, loose bodies, meniscal fragments, and tears and impingements. These symptoms may include localized joint pain with specific rotation and/or flexion, catching or locking, and recurrent effusions associated with the shedding of articulate cartilage debris and fragments. These symptoms should be interfering with daily activities and adversely affecting the patient’s quality of life. The symptoms have not been responsive or relieved by nonsurgical treatments, including activity modification, anti-inflammatory medication, and/or glucosamine sulfate, viscosupplementation, corticosteroid injection (with or without aspiration), physical therapy, stress off-loading with bracing or orthotics, and activity restriction.

The long-term management of degenerative articular disease involves patient education and weight loss (if appropriate). The photos (images) of patient’s articular surfaces taken at the time of chondroplasty (debridement) can be used to reinforce the need to lose weight, build and maintain lower extremity strength, and proactively select nonaggravating activities and exercises.

While arthroscopic chondroplasty and debridement can provide palliative treatment to reduce symptoms from knee osteoarthritis in carefully selected individuals, it is often difficult to predict which patients will definitely benefit. The patient and surgeon should have realistic expectations regarding its possible outcome. The duration of symptomatic relief following chondroplasty is variable and is influenced by the natural history and predisposing factors of the individual’s underlying articular cartilage disease. This is further impacted by the patient’s future use of the knee and subsequent aggravating injuries. Symptomatic improvement is less likely in the presence of more advanced articular cartilage disease (articulating exposed bone particularly on opposing sides of the joint), altered subchondral bone, extremity malalignment, and obesity. Those patients with more advanced articular cartilage degeneration can on occasion experience worsening of their preoperative symptoms following this procedure.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

While imaging techniques for articular cartilage lesions are improving, arthroscopy remains the best method for assessing the grade, size, and location of degenerative articular cartilage changes in the knee joint. Most patients presenting for an orthopaedic surgeon’s evaluation with symptomatic articular cartilage disease have mild to moderate osteoarthritis of the knee and are between 40 and 70 years of age. They usually are coming because of the sudden onset or significant change in their mechanical symptoms and/or effusion. Their assessment begins with a history and physical examination. The duration and severity of symptoms should be established. The onset of the pain related to symptomatic degenerative articular cartilage disease may be insidious; it may develop following an aggravating activity or be associated with a specific traumatic event. The patients who have a more sudden onset tend to respond better to arthroscopic chondroplasty and debridement. In addition to their pain, common symptoms include grinding, clicking, and catching. The mechanical symptoms may be related to loose fragments of cartilage and/or their interaction with degenerative meniscal tissue. Patients may describe a feeling of tightness and/or a sense of swelling related to intra-articular effusions after aggravating activities. The effusion often contributes to their difficulty when squatting or kneeling.

The patient’s discomfort may be exacerbated by twisting motions of the knee, when squatting and turning over in bed at night. The pain is often increased with prolonged standing, walking, or running. The symptoms are usually relieved by rest and restrictions in motion of the knee. The severity of the associated pain may escalate with certain activities and motion and interfere with activities of daily living; night pain can interrupt sleep.

Physical examination includes documentation of the standing lower-extremity alignment in both coronal and sagittal planes. An associated genu varum malalignment is a more common deformity in symptomatic osteoarthritic knees than those with abnormal genu valgus. The presence of a fixed flexion deformity is not unusual in those patients with more advanced joint involvement.

An effusion may be palpable, and the affected joint may feel warmer in the presence of an underlying inflammatory process. The ranges of active and passive motion of the knee without effusion are usually within normal limits in the early stages of articular cartilage disease. Localized joint-line pain may be present on palpation, and the McMurray test may elicit some discomfort in the involved compartment. Associated degenerative meniscal tears and articular cartilage disease are commonly associated with older patients. The knee is usually stable to ligament evaluation in most patients, but excluding underlying ligamentous instability is an important part of the examination and future management.

Aspiration of the joint, with appropriate synovial fluid analysis, should be considered when an effusion is a persistent finding. The shedding of particulate debris from degenerative articular surface(s), and its subsequent digestion and removal, may evoke an inflammatory response within the joint. The synovial aspiration may show particulate debris on gross examination if the needle bore for aspiration is of adequate size. (I prefer an 18-gauge needle for aspirations of symptomatic synovial effusions). Crystal analysis (gout and pseudogout), cell count, and other synovial fluid studies should be performed when an aspirate is sent for laboratory evaluation.

In assessing the patient’s complaints, it is helpful to establish clinically whether the medial, lateral, or anterior compartment(s) of the knee are involved. Is the problem related to predominantly one compartment, or is a tricompartment problem contributing to the patient’s disability? Weightbearing radiographs are useful adjuncts to supplement the clinical findings. They document leg alignment and the extent of articular cartilage interval narrowing, subchondral bone changes, and osteophyte formation.

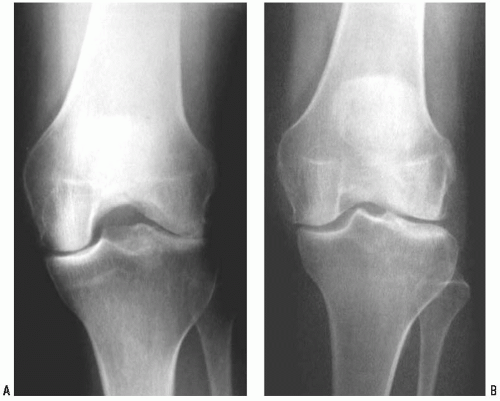

Radiographic imaging of knees with chondral disease should include weight-bearing views. The joint space is best evaluated with a posteroanterior (PA) view, taken of the weight-bearing knees in 20 to 30 degrees of flexion. These PA flexion views may give narrowing changes on weight-bearing views that are not apparent on the same knee fully extended. They document the most frequent region of earlier joint space narrowing (i.e., the middle one third of the femoral condyle) (Fig. 26-1). Radiologic features such as sharpening of the tibial spines, squaring of the joint margins, subchondral sclerosis, and cyst formation may be associated with more advanced degeneration. Tibiofemoral alignment can be assessed on the weight-bearing views of the knee, but a full-lengthextremity film may be required to assess the mechanical axis (if thought to be needed). The greater the varus or valgus deformity and the closer to bone on bone articulation, the less likely the arthroscopic chondroplasty will provide symptomatic relief. The reader is referred to the accompanying chapters on osteotomy, which discuss treatment options for these patients.

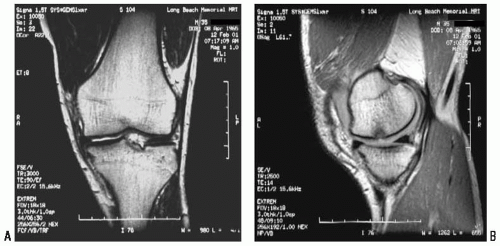

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a useful noninvasive means that may help demonstrate symptomatic articular cartilage lesions. There is often a high correlation with radiographs, but MRI may be particularly helpful when standard radiographs appear normal. A wide variety of MRI pulse sequences have been investigated with regard to their utility in assessment of cartilage image. Among the most useful are fat suppressed proton density (FSPD) and T2-weighted sequences (FST2). A number of gradient recalled sequences continue to be used although no clear consensus on the best pulse sequence has emerged. An example of a MRI grading system is shown in Table 26-1. Current techniques are more accurate in detecting partial or full-thickness cartilage loss (grades III or IV). Experience suggests that MRI and arthroscopic findings may not always correlate. A clinically practical and reproducible system of staging cartilage loss using MRI on a wide scale has yet to emerge.

Nevertheless, MRI is excellent for demonstrating the integrity of the meniscus in the degenerative compartment being evaluated. Magnetic resonance imaging is also capable of providing information on the condition of the underlying subchondral bone and adjacent marrow space (Fig. 26-2).

A radionuclide bone scan may provide additional information in those patients whose pain is out of proportion to the objective findings. As an indicator of increased blood flow, radiotracer uptake may be localized to a single joint surface or compartment. A more generalized uptake may indicate more advanced changes, or even at times an alternate pathology. Recent advances in nuclear medicine techniques include the use of tomographic techniques (SPECT imaging) in conjunction with performing the bone scan. This technique offers increased sensitivity for lesion depiction compared with conventional planar nuclear imaging methods.

The MRI and/or bone scan can be very helpful in the diagnosis of avascular necrosis and its variants of localized bone involvement. Its presence should be explained preoperatively to the patient. Some of these patients may eventually need partial or total knee replacement regardless of what is done. The natural history as best it is known should be explained to the patient, giving the patient the option of additional watchful waiting with possible limited weight bearing.

TABLE 26-1. Grading of Cartilage Lesions | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Eighty-five percent of early symptomatic chondral lesions occur in the medial tibiofemoral compartment. Chondral lesions are most commonly encountered during arthroscopy on the femoral side of the joint, and less commonly cartilage changes are noted on the opposing tibial surface. When there is disruption of the chondral surface (grade IV) encountered during arthroscopy, an associated degenerate meniscal tear in the involved compartment is present at least 70% of the time.

Whenever arthroscopy of the knee is performed, particularly in middle-aged and older patients, the surgeon should be prepared to perform some type of arthroscopic chondroplasty and/or debridement. This includes the debridement and/or removal of loose, undermined, and partially detached articular cartilage, lavage out articular cartilage debris, and excise abnormally mobile and/or degenerative meniscus fragments leaving smoothly contoured and stable rims. The lavage provided at the time of arthroscopy is a method of irrigating and removing the smaller particulate intra-articular cartilaginous debris and degradative enzymes present in the joint.

The informed and written consent obtained before surgery should explain the possibility of this additional procedure(s), risks, rehabilitation, and prognosis. We try to give a clear understanding to each patient of the possibility of the debridement of a potentially symptomatic articular cartilage. This includes an explanation of degenerative cartilage disease and the objectives of a chondroplasty in trying to reduce certain specific symptoms. Patients are also informed that there is a small chance that their knee may be made more symptomatic following the procedure. In our patients we think this risk is less than 5%. The poor results that are seen following arthroscopic debridement are more often in those knees with advanced degenerative disease. This is common when there are articulating bone-on-bone surfaces, significant malalignment, obesity, and in those patients with secondary gain factors (legal or industrial injury) related to their symptoms.

Since there is a possibility of performing the microfracture technique in association with the chondroplasty, this should be discussed, particularly in relation to the postoperative course. See Chapter 27 on the indications and details of microfracture. Surgeons should be prepared to deal with fragmented and loose articular cartilage as well as exposed bone.

SURGERY

On the day of surgery, the “correct” limb is confirmed and marked. The patient’s medical history should be reviewed for allergies to drugs that may be used during and after surgery. We seldom inflate a tourniquet during this procedure; but if is to be used, special attention should be made regarding patients with underlying vascular disease, vascular grafts, or previous deep vein thrombosis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree