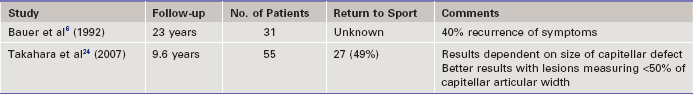

Chapter 40 Osteochondritis dissecans is a localized condition that involves the articular surface with separation of a segment of articular cartilage and subchondral bone. The most common site of osteochondritis dissecans of the elbow is the capitellum, although lesions have been reported in the trochlea, on the radial head, and on the olecranon and in the olecranon fossa.1 Osteochondritis dissecans most often occurs in athletes ages 11 to 21 years who report a history of overuse.2,3 The lesion generally involves only a segment of capitellum and is primarily located in a central or anterolateral position.4,5 Appropriate treatment of this disorder remains controversial. Often treated with benign neglect, osteochondritis is a potentially sport-ending injury for an athlete and in the long term can lead to degenerative arthritis.5,6 Osteochondritis dissecans is primarily a disorder of the young athlete and rarely occurs in adults. The typical patient is age 11 to 21 years, with the majority being age 12 to 14 years.2,3,7 Males are affected more than females; however, this disorder is prevalent among female gymnasts. The dominant arm is almost always involved, and bilateral involvement has been reported in 5% to 20% of cases.8 A history of elbow overuse is often described in association with common sporting activities such as baseball, gymnastics, weightlifting, racquet sports, and cheerleading.36 Most patients report pain, and it is usually insidious and progressive in nature. The pain is often localized over the lateral aspect of the elbow and is exacerbated by activities and relieved by rest. For some patients the location of pain may be poorly defined.8 On clinical examination, palpation laterally over the radiocapitellar joint reproduces tenderness. Elbow range of motion is limited, particularly in extension, and it is not uncommon to observe flexion contractures of 5 to 23 degrees.2,10–13 A loss of elbow flexion is less common, whereas supination and pronation are rarely altered. Any complaints of clicking, catching, grinding, or locking suggest fragment instability or loose bodies. Crepitus and swelling may be present, as well.2,3,8,9 Provocative tests such as the active radiocapitellar compression test may aid in making the diagnosis.14 This test is performed by having the patient actively pronate and supinate the forearm with the elbow in full extension, allowing the dynamic muscle forces to compress across the radiocapitellar joint, thus reproducing symptoms. Plain radiographs are the initial diagnostic test of choice. Standard anteroposterior (AP) and lateral views of the elbow will usually show the classic findings of a radiolucency and rarefaction of the capitellum with flattening or irregularity of the articular surface. A rim of sclerotic bone often surrounds the radiolucent crater, which is typically located in the central or anterolateral aspect of the capitellum (Fig. 40-1). Loose bodies may be present if the necrotic segment becomes detached. Additional studies may be indicated to further evaluate osteochondritis dissecans. Computed tomography (CT) is useful in determining the extent of the osseous lesion as well as the presence and location of loose bodies. CT arthrography more accurately defines the integrity of the articular surface.15 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has become the standard modality for further evaluation.2,16 MRI allows assessment of the articular surface and definition of the size and extent of the lesion (Fig. 40-2). Whereas early, stable lesions show signal changes on T1-weighted images, T2-weighted images remain normal. On the other hand, advanced lesions show signal changes on both T1- and T2-weighted images.2,17 Loose in situ lesions often demonstrate a cyst under the lesion. Magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA) can improve the diagnosis of osteochondral lesions owing to penetration of contrast beneath the disrupted cartilage surface.16,17 Figure 40-2 Coronal (A) and sagittal (B) magnetic resonance images of the same lesion shown in Figure 40-1. Increased signal of the T2 image indicates disruption of the articular surface. Progress and healing can be monitored over time with plain radiographs. If the fragment remains stable, the central sclerotic fragment gradually becomes less distinct and the surrounding area of radiolucency slowly ossifies. A nonhealing lesion in a patient who remains symptomatic despite conservative treatment should prompt the clinician to consider operative treatments.2,5 Stable lesions with intact cartilage and in situ subchondral fragments are managed conservatively.2,8,16 Sports and other aggravating activities are stopped until symptoms have subsided, usually after a period of approximately 3 to 6 weeks. During this time we recommend protecting the elbow in a hinged elbow brace without limitations to motion. Athletes can usually return to sports without restrictions 3 to 6 months after initiation of treatment.9 Patients with intact lesions that are identified early and treated conservatively have the best prognosis. However, it is prudent for the clinician to inform the family of possible long-term sequelae.5,6,8,13,16,18,19 Indications for surgical treatment include persistent or worsening symptoms despite prolonged conservative care, the presence of loose bodies, and evidence of lesion instability including violation of intact cartilage or detachment.2,8,20,21 Multiple surgical techniques have been described and are discussed in the following sections. Nonsurgical treatment is typically selected for patients with early-grade, stable lesions and involves activity modification with cessation of sports participation.22–24 The duration of activity modification is dictated by symptomatology, with a typical regimen consisting of 3 to 6 weeks of rest followed by a return to sport in 3 to 6 months.23,25 Recent studies have reported significantly improved rates of radiographic healing and subjective outcomes in terms of pain and return to sport in patients with open capitellar physes.22,24 Nonoperative treatment is recommended for all stable lesions in patients with open capitellar physes.24 Operative intervention is indicated for lesions that do not improve with appropriate nonoperative treatment, the presence of loose bodies with mechanical symptoms, or the presence of an unstable lesion.25,26 Multiple operative procedures have been described for treating these lesions, including drilling of the defect,26 fragment removal with or without curettage or drilling of the residual defect,5,6,13,18,26–28 fragment fixation by a variety of methods,26,29–32 reconstruction with osteochondral autograft,26,31,33–36 autologous chondrocyte implantation,26,37 and closing-wedge osteotomy of the lateral condyle.26,38 Making comparisons between the reported results of these various operative techniques is difficult because of their largely retrospective nature, the use of different outcome measurements, and the relative infrequency of osteochondritis dissecans.26 Open procedures to remove fragments (Table 40-1) have demonstrated improved results with respect to pain and radiographic parameters when performed in patients with lesions measuring less than 50% of the capitellar articular width.5,23,24 Other studies have shown that removal of loose bodies or excision of the fragment with or without drilling or curettage was not sufficient to regain full function and allow patients to return to their previous level of sport.30,32,39 Kuwahata and Inoue30 performed fragment fixation using a Herbert screw, whereas Takeda and colleagues32 used pullout wiring for fixation (Table 40-2). Both studies performed cancellous bone grafting to fill the crater and possibly to enhance fragment union. All patients showed complete reossification at follow-up, and most returned to their previous sporting activities. Nobuta and colleagues40 found that fragment fixation by flexible wire or thread and revascularization by drilling was effective in patients whose lesion thickness was less than 9 mm (see Table 40-2). Takahara and colleagues24 found significantly improved outcome in terms of pain in patients treated with fragment fixation with bone pegs (see Table 40-2).41

Arthroscopic and Open Management of Osteochondritis Dissecans of the Elbow

Preoperative Considerations

Physical Examination

Imaging

Indications and Contraindications

Nonoperative Treatment

Operative Treatment

Open Surgical Approaches

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Arthroscopic and Open Management of Osteochondritis Dissecans of the Elbow