Arthrofibrosis of the Knee: Diagnosis and Management

Peter J. Millett

Arthrofibrosis of the knee is a difficult clinical problem that usually manifests as knee pain and loss of motion. There are a variety of definitions and causes of arthrofibrosis. In the majority of patients, early recognition and treatment can effectively restore motion and alleviate pain. Successful treatment also allows patients to restore function and to improve their activity level. In order to treat arthrofibrosis appropriately, the clinician must understand the pathoanatomic causes of motion loss so that treatment can be targeted appropriately. The purpose of this chapter is to review the diagnosis and management of arthrofibrosis of the knee.

Pathophysiology

Contributing Factors

Arthrofibrosis in the knee is a complex, multifactorial process with a variety of causative factors. Simple mechanical blocks to extension or flexion cause the most obvious types of motion problems,1 although more subtle types that involve the extensor mechanism may be more common but

more difficult to diagnose. In order to develop effective preventive, diagnostic, and treatment strategies, it is important to understand the myriad causes of motion loss.

more difficult to diagnose. In order to develop effective preventive, diagnostic, and treatment strategies, it is important to understand the myriad causes of motion loss.

Arthrofibrosis is a process in which abnormal scar tissue forms in the knee in response to injury or surgery. The process usually manifests itself as joint stiffness or loss of motion. Sometimes the findings are more subtle and only present as pain. Because the causes for motion loss are broad, in our practice we find it useful to subdivide them into problems that cause loss of flexion and problems that cause loss of extension (Table 11.1). When an individual presents with a motion problem that involves both flexion and extension, it is important to identify the causes of the motion loss. The goals of treatment should be to attempt to re-establish full extension first and then to restore flexion, because the loss of flexion is usually better tolerated and is also easier to treat.2,3 There are also types of arthrofibrosis that affect only the extensor mechanism and do not result in loss of motion. These are more subtle forms of the disease that will also be discussed in this chapter.

Prior Surgery

Prior surgery is a common cause of knee stiffness. Historically, arthrofibrosis and motion problems were relatively common after ligament surgery, particularly anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) surgery. Fortunately, the incidence of clinically relevant motion loss after ACL reconstruction has decreased with a better understanding of risk factors, with improvements in surgical technique, and with better rehabilitation programs.4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11 In the literature, the incidence of motion problems after ligament injury or surgery has been variable.3,4,5,8,9,12 Some of this variability may have been the result of inconsistencies across studies in how the injuries were defined, in how the injuries were treated both surgically and rehabilitatively, and in how the motion loss was defined within each study. Shelbourne and Rask13 defined motion loss very strictly and stressed the importance of using the contralateral knee as the norm for comparison. In their report, any deviation in motion from that of the normal, contralateral limb was considered abnormal or arthrofibrotic. Other authors have defined arthrofibrosis as a deviation of 5 degrees from full extension.10

Table 11.1 Causes of Motion Loss | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||

In our practice, we consider loss of motion to be a deviation in flexion or extension from the contralateral side. Furthermore, we even recognize that there are more subtle forms of arthrofibrosis in which the flexion and extension arcs are symmetrical, but because of loss of mobility in the extensor mechanism (patella, patellar tendon, quadriceps tendon) or because of stiffness in the joint capsule, the patients are considered to have arthrofibrosis. Loss of mobility in the extensor mechanism, although less recognized, can have relevant clinical manifestations most commonly presenting as anterior knee pain. This type of arthrofibrosis can be particularly troubling for high-level athletes. In most instances, arthrofibrosis becomes more clinically relevant as the degree of motion loss increases, with significant disability occurring when the side-to-side difference in extension is greater than 10 degrees.

Anterior Cruciate Ligament Nodule

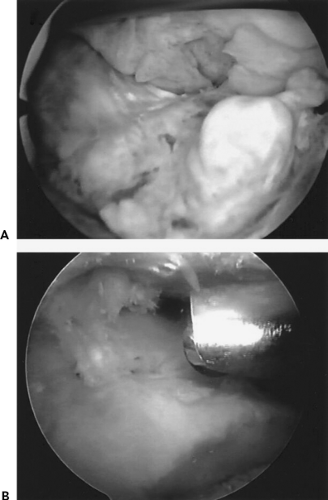

In cases of motion loss following ACL reconstruction, a fibroproliferative scar nodule (ACL nodule or cyclops lesion) can occur, which typically results in pain during knee extension. This localized form of arthrofibrosis usually begins to manifest itself clinically at about 2 to 3 months postoperatively. ACL nodules are most commonly located anterolateral to the tibial tunnel3,14,15 and are typically attached to the ACL graft, as well as to the soft tissue overlying the tibia (Fig. 11.1). The nodules are composed of dense fibrous tissue with a central area of granulation tissue. As the knee moves into extension, impingement occurs between the ACL nodule and the intercondylar notch, blocking terminal extension. Hypertrophy of the graft or other soft tissue scarring in the notch can cause a similar block to extension.16,17

Graft Malposition

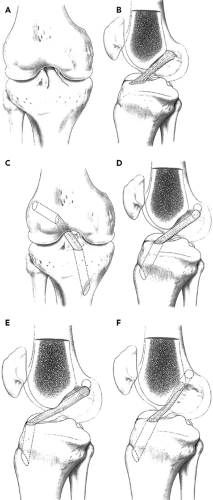

Technical factors such as graft malposition can also contribute to postoperative loss of motion3,18,19 Although technically not a form of arthrofibrosis, it is important to consider graft malpositioning in the differential diagnosis of patients who present with motion loss of the knee. Proper graft positioning is essential to prevent graft impingement (Fig. 11.2) and to allow normal knee kinematics. ACL grafts that are placed in the wrong position can obviously interfere with normal knee motion.20,21 Graft position must be accurate in both the coronal and sagittal planes to ensure that the graft functions correctly and does not cause limited motion.

When the cruciate ligaments are reconstructed, the tibial and femoral attachment sites must be anatomically accurate

to restore knee stability while allowing normal motion. The position of the ACL attachment/tunnel on the tibia affects both range of motion and impingement in the intercondylar notch.22 Malposition can cause excessive stress on the graft, development of an ACL nodule, or graft failure. In our experience, a tibial tunnel that is placed too far anterior results in limited flexion because of excessive graft tension and also limited extension from graft impingement (Fig. 11.2E). The graft must also be placed in the correct coronal plane position with enough obliquity across the joint to re-establish the normal rotational stability and to prevent persistent rotational instability.

to restore knee stability while allowing normal motion. The position of the ACL attachment/tunnel on the tibia affects both range of motion and impingement in the intercondylar notch.22 Malposition can cause excessive stress on the graft, development of an ACL nodule, or graft failure. In our experience, a tibial tunnel that is placed too far anterior results in limited flexion because of excessive graft tension and also limited extension from graft impingement (Fig. 11.2E). The graft must also be placed in the correct coronal plane position with enough obliquity across the joint to re-establish the normal rotational stability and to prevent persistent rotational instability.

Improper placement of the femoral tunnel can also be a cause for loss of motion. In the sagittal plane, the ideal femoral tunnel is placed in the posterior wall of the femoral notch, leaving 1 to 2 mm of posterior wall remaining.20 An anterior femoral tunnel can lead to loss of

motion, graft failure, or both (Fig. 11.2F). Coronal plane abnormalities of the femoral tunnel, most commonly an excessively vertical tunnel, are more commonly associated with persistent rotational instabilities. When using a transtibial drilling technique for ACL reconstruction it is important to recognize that the femoral tunnel position is influenced by the tibial tunnel position.

motion, graft failure, or both (Fig. 11.2F). Coronal plane abnormalities of the femoral tunnel, most commonly an excessively vertical tunnel, are more commonly associated with persistent rotational instabilities. When using a transtibial drilling technique for ACL reconstruction it is important to recognize that the femoral tunnel position is influenced by the tibial tunnel position.

Overtensioning of the graft has been proposed as a potential cause of motion loss,23 but we believe that excessive graft tension in a properly positioned graft will not, in and of itself, cause motion loss because of the viscoelastic properties of the ligament when the knee is moved through a full range of motion.

Prolonged Immobilization

Many studies have demonstrated the detrimental effects of prolonged immobilization on periarticular cartilage, bone, and soft tissues. Through the years, joint immobility has been one of the more common causes of arthrofibrosis and motion loss.24,25,26 Fortunately, with modern rehabilitation programs that stress early motion and weightbearing, there are fewer reports of motion problems and better outcomes.9,10,27,28,29,30 Our current rehabilitation programs after ACL reconstruction, meniscus repair, or cartilage restoration focus on early motion to prevent arthrofibrosis. A more recent addition to our program is patellar mobilization to prevent scarring around the patella and patellar tendon.

Infection

Infection should always be considered a cause or contributing factor to arthrofibrosis. Unrecognized or untreated infections will cause an inflammatory response that results in scarring and loss of tissue compliance. This results in pain and stiffness. Although fulminant infections with highly virulent organisms may be easily recognized, more subtle infections with organisms of low virulence may be completely missed. Infection must always be considered in the diagnosis of arthrofibrosis and must always be considered a potential cause of the disease until proven otherwise. The workup of suspected infection is discussed later in this chapter.

Anterior Interval/Extensor Mechanism Scarring

Paulos et al.25 were among the first researchers to describe the infrapatellar contracture syndrome as a cause of posttraumatic knee stiffness with patellar entrapment and patella infera (baja). Patients who develop infrapatellar contracture syndrome have a combination of restricted knee extension and flexion associated with patellar entrapment. This is another localized form of arthrofibrosis that is caused by an exaggerated pathologic fibrous hyperplasia in the anterior fat pad.25,32,33,34,35,36 Prolonged immobility and lack of extension, particularly after intra-articular ACL reconstruction, seem to be contributing factors. The fat pad becomes densely adherent to the underlying tibia, resulting in diminished excursion of the patella and loss of motion. In more subtle cases of anterior interval scarring, flexion and extension arcs may be full, but the infrapatellar fat pad and patellar tendon adhere to the anterior tibial cortex below the inferior pole of the patella. The normal pretibial recess of the knee is obliterated, and the anterior interval adhesions prevent normal motion of the intermeniscal ligament over the tibial plateau during flexion and extension. Furthermore, the anterior horn of the medial meniscus fails to glide anteriorly and posteriorly with flexion and extension. These observations can be made at the time of arthroscopy.32,33,34,35,36

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree