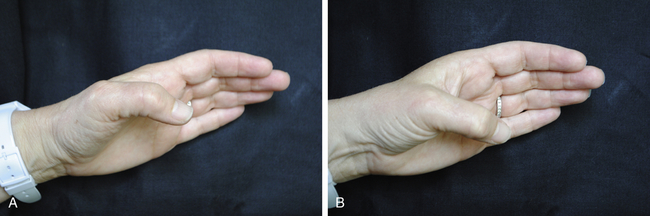

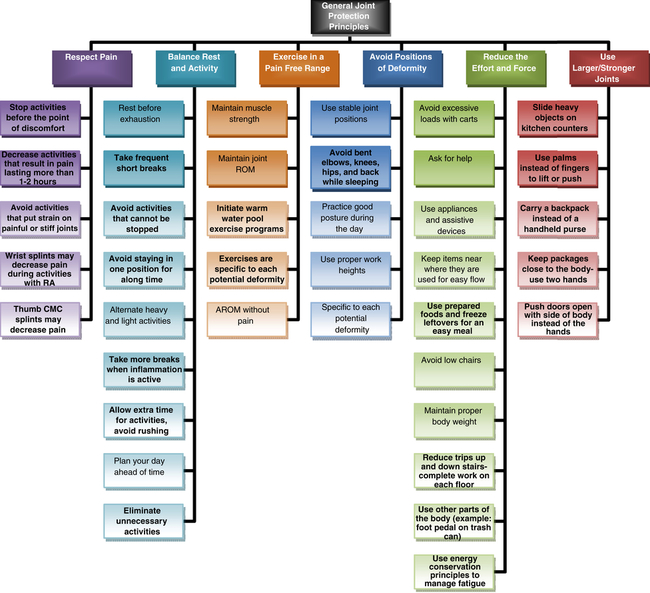

Arthritis is the leading cause of disability in the United States.1 More than 100 diseases and conditions fall into the category of rheumatic diseases.2 The most common, osteoarthritis (OA), affects nearly 27 million Americans over the age of 253 and is the most common joint disorder throughout the world.4 OA is associated with a defective integrity of the articular cartilage and changes in the underlying bone.5 Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) affects more than 1.5 million Americans6 and is a chronic, systemic, inflammatory, autoimmune disorder.7 The inflammatory process associated with RA manifests itself primarily in the synovial tissue.8 In addition to RA and OA, the therapist also may treat other rheumatic diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus (a systemic autoimmune disease characterized by inflammation and blood vessel abnormalities), gout (a disorder caused by uric acid or urate crystal deposition), bursitis (inflammation of the bursa), and fibromyalgia (diffuse widespread pain often with specific tender points). 2, 3, 7, 8 In the United States nearly 50 million adults over the age of 18 report being told by a physician that they have some form of arthritis, and over 21 million adults have activity limitations attributed to arthritis.9 Clearly, with this level of prevalence, many therapists at some time will find these clients on their caseload, or be questioned about arthritis by colleagues and family. The therapist must have an understanding of the disease process, potential deformities, and how it can affect the clients’ activities of daily living (ADLs). Client education about the disease and awareness of treatment options are also critical aspects of the treatment process. OA is often called the wear-and-tear disease, but research demonstrates that the breakdown in the articular cartilage is due to both mechanical and chemical factors.10 Changes in the articular cartilage and the subchondral bone result from the chondrocytes failing to maintain the necessary balance of the extra cellular matrix.11–13 Complex biomechanical factors appear to activate the chondrocytes to produce degradative enzymes.14, 15 This degradation then corresponds to failure of the articular cartilage to act as a shock absorber, resulting in progression of the disease. Mechanical factors, such as abnormal loading of the joint from trauma, heavy labor, joint instability, and obesity, can increase the risk of OA.16 Aging is also a risk factor, because aging cartilage contains less water and fewer chondrocytes, decreasing the capacity of the cells to restore and maintain the cartilage.13 Clients from all corners of the world report similar patterns of joint involvement12 including the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints (35%) and the carpometacarpal (CMC) joint of the thumb (21%).9, 17–19 In addition, 50% of patients with DIP involvement also have proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint involvement.20 Affected persons have a genetic susceptibility, and OA occurs more frequently in women over age 50 than in men of the same age. 13,18 In addition to the cartilage breakdown, new bone formation (or osteophytosis) can occur, resulting in pain and limitations of joint movement. Osteophytes, or bone spurs, occurring at the metacarpophalangeal (MP) joints can contribute to triggering (limited digital range of motion [ROM] caused by dragging of the tendon as it passes through a pulley) of the flexor tendons,4 or locking (the digit locks into flexion as the tendon fails to pass through a pulley). Nodules can occur with OA at the PIP joint and are called Bouchard’s nodes, and at the DIP joint they are called Heberden’s nodes.13 Deformities as a result of this arthritic process include a mallet finger deformity at the DIP joint and lateral deviation or boutonniére deformities at the PIP joint.18 The client may also demonstrate reduced ROM, pain, crepitus (grating or popping as the digit flexes and extends), and signs of inflammation.9 In the lower extremity, the knees and hips commonly are affected. Currently, no cure is available for OA. Treatment is based on the specific needs of each patient and the stage of the disease. In the early stage, radiology reveals a reduction in the joint-spaces and swelling of the periarticular tissues; the moderate stage demonstrates osteophytes, subchondral sclerosis, and cysts. In the late stage, bone erosion, subluxation, and fibrotic ankylosis are common.18 Regarding postoperative care, the timelines follow the phases of wound healing. This includes the inflammatory phase during the first few days after surgery. Healing continues to the proliferative phase or fibroplasia, which often lasts from 4 days to approximately 3 weeks after surgery and is when the fibroblasts lay beds of collagen. During this stage, many of the postoperative protocols incorporate a balance between specific orthoses and gentle exercise. Finally, the remodeling phase or maturation phase occurs, which often begins 3 weeks after surgery and can last several years with gradual increase in the tensile strength of the collagen fibers.21 The evaluation should include an assessment of pain, active range of motion (AROM), joint stability, joint inflammation, palpation, and ability to do ADLs. Pain can be measured at rest and with activities with a 10 cm visual analog scale (VAS), with 0 being no pain and 10 being severe pain.22 I have observed clinically that many clients with arthritis tend to underestimate their pain. Document areas of inflammation by specifying which joints are involved. If the joint is warm and red, it may be in an acute inflammatory stage, and this should be noted. The evaluation of ADLs should include home, work, and leisure activities, because clients often seek help when their meaningful activities are threatened. Standardized tests, such as the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM)23 and Arthritis Impact Measurement Scales (AIMS) health status questionnaire,24 can be helpful in determining areas of ADL limitations and setting goals in collaboration with the patient. In regards to the evaluation of the basal joint of the thumb with OA, the Eaton classification has been widely used to define severity as well as guide treatment.25 The stages are highlighted in Table 33-1. It is important to note that treatment should be based on the severity of the symptoms reported by the patient and not simply on the radiographic stage.26 TABLE 33-1 Eaton Radiographic Classification for Staging Basal Joint Arthritis From Eaton RG, Glickel SZ: Trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis. Staging as a rationale for treatment, Hand Clin 3(4):455-471, 1987. Grating or crepitus evident at a joint can indicate damaged cartilage. The grind test for degenerative joint disease at the CMC joint involves compressing the joint while gently rotating the head of the metacarpal on the trapezium27 (Fig. 33-1). Pain and crepitus at the CMC joint generally are considered positive findings. Joint protection principles ideally are initiated early in the disease process in hope of decreasing stress and damage to the involved joints.28–30 This is completed through altered work methods to educate the client on proper joint alignment and the use of adaptive equipment. Joint protection for OA should also take into account the specific deformity or potential deformity, which may include instability of the CMC joint and the deformities of the involved IP joints.29, 30 Common joint protection principles for both OA and RA are categorized by themes in Fig. 33-2. Because excessive pinching during ADL imparts large forces to the unstable thumb CMC joint, educating patients in techniques that decrease pressure and force applied to the thumb CMC joint is important.31 There is moderate evidence to support joint protection education and adaptive equipment for increased hand function and pain reduction in patients with OA.32 The European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR)33 in their systematic review recommended joint protection education combined with an exercise regimen for all patients with hand OA. Another systematic review found moderate evidence to support combining joint protection with adaptive device provision for increased hand function and pain reduction.32 Adaptive equipment used in one study included enlarged writing grips, Dycem, an angled knife, a book holder, and other equipment based on the client’s ADL34 and resulted in improvements in grip strength and global hand function. Adaptive equipment that can help to increase leverage and also distribute the pressure in the hand includes larger-diameter pens, broad key holders, large plastic tabs on medicine bottles, and car door openers. As handle diameter increases, reduced digit force on a tool is needed. Basic science in tool design has developed in the engineering fields to accurately measure these forces. It is reported that in normal hands, the most comfortable handle is 19.7% of the user’s hand length35 and that the ideal tool handle design is a cylinder with a 33-mm diameter.36 It has also been determined that to decrease the maximum push pull force on a tool, a cylindrical handle must be parallel to the push/pull direction.37 It has also been reported that a handle design that reduces wrist ulnar deviation requires the least amount of grip force.38 Additional joint protection techniques include moving objects out of the hand (for example, using a shoulder strap tote bag instead of a brief case with a handle) to help distribute the pressure to larger joints when carried closer to the body. 28 Clients often place strong forces on the hands when lifting themselves from one position to another. In some cases, adaptive equipment can reduce the effort on the lower extremities (such as, a lift chair, a shower chair, or elevated toilet seat) by reducing the stress placed on the hands. The therapist should also take into consideration the client’s sociocultural context. The client may or may not have insurance coverage or finances for adaptive equipment or orthoses. Carefully discuss options with the client and weigh them in terms of cost versus value in meeting the client’s specific needs. The therapist should be aware of community resources, including civic, community, or religious organizations that may provide adaptive equipment (for example, grab bars and elevated toilet seats) for specific socioeconomic situations. For further information on joint protection, the reader is encouraged to review the work Adult Rheumatic Diseases (2000), by Melvin and Ferrel.39 Modalities have a long history of use in the treatment of arthritis. Many patients with OA report beginning their day with a warm shower or bath as increased tissue temperatures result in temporary neuromuscular effects that decrease pain and muscle tension.40 Types of superficial heating agents include paraffin, Fluidotherapy, hot packs, microwave packs, hydrotherapy, and electric mitts. Decreasing pain and maintaining or improving ROM is a primary goal in the application of these agents. Research continues to add to the body of knowledge concerning heat and other modalities for OA, including non-thermal ultrasound, electrotherapy, cryotherapy, and low level laser therapy. 41 A systematic review by Zwang, et al.33 examined the benefits of heat and ultrasound and found predominantly only level IV evidence (expert opinion). According to the review by Valdes and Marik,32 there is weak to moderate level evidence supporting the use of heat modalities in decreasing pain and improving grip strength in patients with OA, and low level laser therapy was no better than the placebo. General principles of exercise include avoiding painful AROM and PROM by working within the client’s comfort level. General AROM exercises for the hand include wrist flexion and extension, gentle digit flexion and extension, and thumb opposition. There is moderate evidence to support hand exercises in OA for increasing grip strength, improving function, improving ROM, and pain reduction.32 Combining joint protection and pain-free hand home exercises were found to be an effective means to increase hand function, as measured by grip strength and self-reported global functioning in persons with hand OA.42 Exercise programs that utilize AROM as opposed to pinch strengthening 32,43 were found to be more effective. One study that used resistive pinch strengthening resulted in some of the participants leaving the study due to increased hand symptoms.44 For example, even light putty-pinching exercises impart large forces31 to an unstable CMC joint that may aggravate a potential deformity. Stability must not be sacrificed for a possible increase in strength. A stable pain-free thumb provides a post against which the digits can grip and pinch effectively. Stretching and massage of the first web space may help prevent the adduction contracture and subsequent MP hyperextension deformity.45 Thumb web space stretching or widening can be done by having the client grasp a one inch wooden dowel (Fig. 33-3) as part of the HEP, as well as techniques to relax the adductor pollicis (AP). Anatomically, strengthening the first dorsal interosseous may help provide stability to the base of the CMC, because it originates at the base of the first metacarpal.45 In regards to the tendons, grip strengthening is a common example of an exercise that can aggravate inflamed flexor tendons. A digit that is triggering or locking will not be improved with grip strengthening exercises, which can increase these symptoms. Research on overall body conditioning has been reported to result in decreased pain and increased static and dynamic grip strength.46 A study on low impact general conditioning demonstrated increased aerobic capacity, decreased depression, and decreased anxiety in patients with arthritis.47 OA can affect all of the joints of the thumb with a swan neck deformity as one of the most common. It is often characterized at the CMC joint by metacarpal adduction and subluxation from the trapezium, MP joint hyperextension, and IP joint flexion (Fig. 33-4). Pinch is often painful because the CMC subluxation becomes more pronounced during heavy pinch activities. The thumb IP joint sometimes assumes a flexed position. The Eaton classification has been widely used to define severity and guide treatment of this deformity through radiographs.25 The Eaton stages are highlighted in Table 33-1.When evaluating the thumb, determine the specific pattern of deformity so that treatment can be more specific in terms of orthotic support and therapeutic management. If the orthosis fits well, the client will report decreased pain with pinch activities, because it is stabilizing the CMC joint in the proper position. Radiographs during active pinch can verify that the orthosis is properly maintaining the metacarpal on the trapezium.49 CMC interposition arthroplasty involves resection of CMC joint that then allows the metacarpal to return to an abducted position.48 A donor tendon is rolled up and inter-positioned in the joint space. The ligaments are usually reconstructed and help to provide the CMC joint stability. Hyperextension of the MP joint may be corrected as well. In most cases the client is in a cast for 4 to 6 weeks and then is referred for an orthosis. The postoperative course varies from surgeon to surgeon. When the surgeon allows CMC AROM, it is important to help the client learn how to move it properly. Frequently, these clients have been compensating before surgery by only moving their thumb IP and MP joints. One exercise technique for this is to have the client flex the thumb IP and MP joints (and try to keep them flexed) while moving the CMC joint in gentle flexion and extension (Fig. 33-13). Techniques to restore the thumb web space and strengthen the first dorsal interosseous (see Fig. 33-5) may also be helpful in the promotion of CMC stability.45 The postoperative orthosis may be worn anywhere from 6 to 12 weeks from the date of surgery depending on the preferences and protocols of individual surgeons.

Arthritis

Osteoarthritis

Pathology

Timelines and Healing

Evaluation

Eaton Stage

Radiograph

Stage I

Normal appearance of articular surface and slight joint space widening.

Stage II

Minimal sclerotic changes of subchondral bone with osteophytes and loose bodies less than 2 mm.

Stage III

Trapeziometacarpal joint space markedly narrowed and cystic changes present. Subluxation of the metacarpal may have occurred. Osteophytes and loose bodies greater than 2 mm.

Stage IV

Presence of scaphotrapezial joint disease with narrowing.

Non-Operative Treatment

General Joint Protection Principles

Modalities

Exercise

The Thumb

Diagnosis-Specific Information that Affects Clinical Reasoning

Operative Treatment

Therapy after Carpometacarpal Interposition Arthroplasty