Chapter 5 Applying the biopsychosocial model to the management of rheumatic disease

KEY POINTS

Living with a rheumatological condition has the potential to impact on physical, psychological and social function.

Living with a rheumatological condition has the potential to impact on physical, psychological and social function.INTRODUCTION

Living with a chronic condition, such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), impacts all functional domains. Health professionals help patients develop coping skills to minimise the condition’s effects on physical and psychological wellbeing. To do this effectively health professionals must understand why and how people adopt or reject certain health behaviours. By utilising the biopsychosocial model of care, illness impact on physical, psychological and social aspects of function is addressed and a wider range of therapeutic options offered that have meaning and relevance to the individual.

SECTION 1: THE BIOPSYCHOSOCIAL MODEL AND ITS IMPORTANCE IN ARTHRITIS MANAGEMENT

Adopting a biopsychosocial approach to care has increased the range of therapeutic options for patients. Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), which aims to identify and change maladaptive patterns of thought and behaviour, is of benefit in patients with RA. In newly diagnosed RA patients, CBT improves a patient’s sense of control regarding their condition and prevents development of negative illness perceptions (Sharpe et al 2003). CBT is also useful for patients with depression (Parker et al 2003).

Other psychological interventions involve improving confidence in carrying out specific behaviours, i.e. self efficacy, which will be discussed in Section 4. If a person believes they can play an active role in managing some of the impact of their condition, through employing strategies such as pacing, goal setting and exercise, they are more likely to do so than a patient with little or no such confidence. Active self-management is associated with higher levels of adherence. Even if the intended goal is not achieved, the process of striving for it leads to better outcomes (Jerant 2005).

Involving significant others in care management can also have a positive effect on outcomes. If the family is unaware why an individual is encouraged to pace their activities, this may be perceived as ‘laziness’ and lead to family conflict. Spouses of patients attending an education programme to increase their knowledge of RA experienced a change in their perceptions towards the condition, which were largely negative before the programme (Phelan et al 1994). The importance of the family on outcome was illustrated in a study of the benefits of behavioural interventions to minimise pain in patients with RA. Intervention incorporating family support was more effective in reducing pain than the intervention with the family alone (Radojenic et al 1992). Adopting a biopsychosocial model of care ensures all factors influencing a patient’s ability to manage and cope with their condition can be identified and, where possible, addressed.

SECTION 2: THE IMPACT OF RHEUMATOLOGICAL CONDITIONS

Patients are individuals with a life history, beliefs, standards and expectations (Bendor 1999). RA cannot be considered solely in terms of its physical consequences. The potential psychological, social and economic impact must be considered.

WORK

Work disability can occur early in arthritis (Fex et al 1998). People with a musculoskeletal condition are more likely to stop working if they:

Cox (2004), focusing on the needs of newly diagnosed RA patients, found that being able to continue working was a major concern: ‘The only question I could think of, is the question I really want answering – am I going to get back to work full-time?’. A National Rheumatoid Arthritis Society (2003) survey showed 54% of participants attributed not being in full-time work to RA and 30% of employed participants worked part-time because of RA. Mancuso et al (2000) found those seemingly successfully employed still faced major challenges, made major adaptations in order to stay at work and still perceived their jobs to be in jeopardy. Early intervention through liaison with employers, consideration of alternative ways of working, work place assessment and if necessary retraining is important to keep patients at work (see Ch. 9: Occupational therapy). Vocational issues that may need considering are shown in Box 5.1.

LEISURE

Engaging in a specific leisure activity will be influenced by the individual’s level of motivation, and the belief participation can be done to a reasonable standard. The physical and psychological impact of arthritis, such as pain, reduced muscle strength, fatigue and reduced self esteem, may hinder both the desire and ability to partake in leisure. Many difficulties are faced participating in leisure (Fex et al 1998, Hakkinen et al 2003, Wikstrom et al 2005). Inaccessible facilities, lack of transport, absence of support or negative attitudes from others may all impact negatively on leisure (Specht et al 2002).

MOOD

Depression in RA is 2–3 times higher than in the general population (Dickens & Creed 2001). Data from baseline co-morbidity levels in over 7,000 patients starting biologic treatments found 19% had a formal diagnosis of depression at any one time (Hyrich et al 2006).

Depression in RA is linked to:

(Dickens & Creed 2001, Lowe et al 2004, Sheehy et al. 2006).

SOCIAL SUPPORT

Ryan et al (2003) demonstrated that patients wanted to remain active in both domains. Aspects of social support enhancing control perceptions include:

Many inflammatory conditions are characterised by unpredictability regarding symptom occurrence, treatment efficacy and overall prognosis. Different levels of support will be required from health professionals related to patients’ identified needs (Box 5.2).

SEXUALITY AND BODY IMAGE

Sexuality is an individual self-concept expressed as feelings, attitude, beliefs and behaviour (RCN 2000). RA features which impact negatively on sexuality and body image include joint pain and stiffness, fatigue, low mood, physical changes and treatment visibility, including splints (Hill et al 2003). Patients indicate they would like the opportunity to discuss sexuality concerns with healthcare professionals (Hill et al 2003) but due to a lack of privacy, time, knowledge and skills, this often does not occur. Many types of arthritis extensively affect people’s lives. Living with chronic pain considerably contributes to this.

SECTION 3: PAIN

Pain is an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage (International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) 1994). It is a common symptom across rheumatic conditions. It is a unique, subjective and unverifiable person experience (Turk & Melzack 1992). Acute pain is often transient and the source of pain is identifiable and treatable, e.g. active synovitis of the knee. Chronic pain is an ongoing experience associated with a plethora of other symptoms including anxiety, depression and sleep disturbance.

Patients with RA cite pain as their most important symptom (Minnock et al, 2003). Pain is associated with impaired quality of life, depression and disability in both RA and OA (Spranglers et al 2000). Chronic pain in fibromyalgia results in reduced physical activities, increased mood symptoms, withdrawal from the workplace and increased use of health care services (Hughes et al 2006). When helping patients manage their pain, a biopsychosocial model aids fully comprehending the pain experience and enables planning care that is meaningful for the patient.

PAIN MECHANISMS

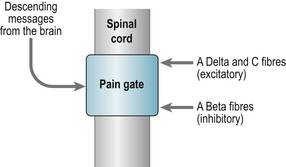

Melzack and Wall’s gate control theory of pain (1965) revolutionised understanding of pain mechanisms (Fig. 5.1). This demonstrated that the transmission of pain messages could be modulated within the spinal cord via descending messages from the brain (our cognitions and emotions) or altered by activating another source of sensory receptor (e.g. exercise to release endorphins).

PAIN RECEPTORS

Peripheral sensory nerves transmit signals from the peripheries to the central nervous system enabling stimulus identification. Alpha delta fibres (thin and myelinated) transmit the sharp pain of an acute injury and slower C-fibres (unmyelinated) produce the dull aching pain of a more persistent problem or the burning quality of neuropathic pain (McCabe 2004).

Sensory nerves deliver information from the peripheries to the dorsal horn where they terminate. This information is then interpreted by transmission cells (T-cells) transmitting information to the local reflex circuits and the brain. When the Alpha delta and C fibres are stimulated T cells are activated resulting in the substantia gelatinosa (SG) being suppressed so that the ‘pain gate’ opens and messages pass to the brain to be perceived as pain. When large fibres become activated (Alpha beta) they suppress T cell activity and close the gate. Alpha beta fibres transmit the sensation of touch. Acupuncture and electrical nerve stimulation work on the same principle and excite large fibre activity. Nerve impulses descending from the brain can also operate ‘the gate’.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree