Chapter 11 Applying psychological interventions in rheumatic disease

KEY POINTS

The theories, research and professional practice approaches used by health psychologists provide a rich basis for the development of practical interventions for people with rheumatic disease that therapists can deliver

The theories, research and professional practice approaches used by health psychologists provide a rich basis for the development of practical interventions for people with rheumatic disease that therapists can deliver There are many internet resources with information on health psychology, health and rheumatic disease (see useful websites)

There are many internet resources with information on health psychology, health and rheumatic disease (see useful websites) Experiencing a rheumatic disease is a chronic stressor with psychological as well as physical impact. Understanding an individual’s illness perceptions might help the patient and their health professional make treatment decisions that are most acceptable for both parties

Experiencing a rheumatic disease is a chronic stressor with psychological as well as physical impact. Understanding an individual’s illness perceptions might help the patient and their health professional make treatment decisions that are most acceptable for both partiesINTRODUCTION

In this chapter we will consider how physiotherapists, occupational therapists, nurses and other allied health professionals benefit from understanding how psychological interventions can be applied to people with rheumatic disease. We will focus on cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) approaches you might consider applying and provide information about assessments of stress, illness perceptions and mood you can use in practice. The role of health psychologists in rheumatology was discussed in Chapter 1 and here we will also consider how they might add breadth to multidisciplinary teams (MDTs).

This volume is timely given the changing emphasis within the healthcare system, both in the UK and internationally. Health professionals are encouraged to promote self-care (or self-management) for patients with long-term conditions (Department of Health 2006). We will outline studies demonstrating the application of psychological theory and practice to facilitating self-management by enhancing concordance between patients and health professionals, building upon Chapter 5 (Biopsychosocial care) and chapter 6 (Patient education and self-management). A recent meta-analytic review by Dixon et al (2007) identified that psychosocial interventions boost active coping efforts people with arthritis engage in. These interventions improve anxiety, joint swelling, as well as depression, functional ability and self-efficacy over pain. We will explain some of these concepts, like self-efficacy and coping in more detail (see also Chs 5 & 6). Finally, we provide some examples of practical tools to foster self-motivated behaviour change and improve outcomes of people with rheumatic diseases.

STRESS AND CHRONIC ILLNESS

The idea of effective ‘coping’ is related to how much ‘stress’ the person feels under. So we need to define these concepts and consider the theoretical background they arise from (Box 11.1).

BOX 11.1 Frequently asked question: what is ‘stress’?

In the language of the modern day we use the words ‘stress’ or ‘stressed’ to explain a feeling or emotion usually arising from a particular event or situation. We say we feel ‘stressed’ when we perceive that the demands of a situation outweigh the perceived resources that we have to meet it (Lazarus Folkman 1984). The key word here is perceived.

Stress is normal. Most of us say we feel ‘stressed’ sometimes. You may find studying or elements of your job stressful, i.e. you perceive these stimuli or events as stressors. Lazarus & Folkman (1984) described how our reactions to such stressors include cognitions, emotions, behaviours and physiological changes. Cognitions are thoughts, such as the threat of how bad the outcome could be, how challenging it is and how much control you have over the situation (Lazarus & Folkman 1984). The emotional, behavioural and physical reactions might include feeling worried, thinking about the perceived problem a lot, working longer hours to complete work and experiencing physical symptoms of anxiety, such as ‘butterflies’ in the stomach (Lazarus & Folkman 1984).

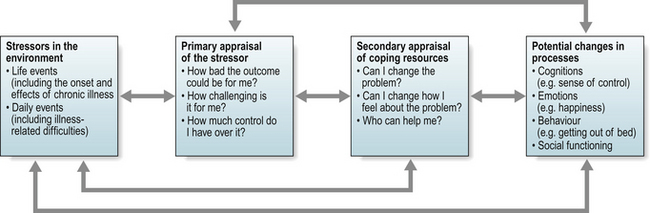

Alternatively, you might view your courses or tasks at work as exciting, challenging and feel elated by the prospect. An individual’s interpretation or perception of the stressful event and their response to it is the key element here. People experience different events, or different elements of events, as stressful or not based on their interpretation of the event. How you think about a given situation influences what you do. In reality, the experience of ‘stress’, and the ways in which we cope with it, is a process of interactions and adjustments in which we alter the impact of the stressful event or situation by making adjustments in our behaviours, cognitions and emotions (Lazarus & Folkman 1984, Fig. 11.1).

Chronic illnesses, like the rheumatic diseases, can be conceived as stressful events at both a physical and psychosocial level. They lead to coping responses from early onset (Treharne et al 2004), which are revised and adjusted throughout the disease course. This is a specific application of the stress-appraisal-coping model. People constantly appraise their coping responses for their usefulness, make adjustments and re-appraise the situation as necessary (Lazarus & Folkman 1984).

The concept of coping was introduced in Chapter 5. Coping involves a process of managing the emotional and physical demands of the stressful situation. Although coping responses used may not actually solve the problem or alter the demands of the situation per se, they may enable the individual to alter their perception of the situation and reconstruct their thinking in more positive terms. Coping responses can act in two ways to reduce psychological stress (Lazarus & Folkman 1984):

PROBLEM-FOCUSED COPING

The individual acts to alter the problem causing the stress. This is employed when a person believes that the situation is changeable and they have, or can get, the resources to help them. These beliefs can easily be facilitated by a therapist offering practical interventions and psychological support enhancing active problem-focused coping strategies, such as making a plan of action and following it. Such coping strategies are associated with better psychological outcomes and less depression among people with rheumatic disease (Hampson et al 1996, Treharne et al 2007a, Zautra & Manne 1992).

EMOTION-FOCUSED COPING

The individual acts to cope with the emotional effects of a problem. Often people engage in this type of coping when they believe they cannot alter the stressor or have insufficient resources to cope with the problem (Lazarus & Folkman 1984). These strategies often involve avoidance, which can be active in nature, such as keeping busy with some other task, or passive in nature, such as social withdrawal. Emotion-focused coping does not always involve avoidant behaviour, for example trying to see the positive side of the situation is an active emotion-focused strategy (Treharne et al 2007a).

In the UK, facilitating coping strategies is becoming increasingly relevant as the government places further onus upon individuals to take responsibility for their own health and well-being, supported in full by multidisciplinary services within the NHS and their selected partnerships (Department of Health 2006). ‘Standards of care’ have been published by the Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Alliance (ARMA) in the UK for a variety of rheumatic diseases, including back pain, connective tissue diseases, inflammatory arthritis and osteoarthritis (http://www.arma.net.uk). ARMA proposed self-management training should be available for individuals with rheumatic disease at any stage of their illness: via the Challenging Arthritis programme run by the charity Arthritis Care (see Barlow et al 1998): the generic Expert Patient Programmes, now available throughout the UK within NHS primary care trusts (see Expert Patients Programme 2009); and health professional led self management programmes. Many people will be happy to seek information and learn self-management strategies through group-based interventions, but not all are able to or comfortable with such courses (Hale et al 2006b). Ongoing individualised treatment plans by the multidisciplinary team are still required.

ASSESSING STRESS

Assessing causes of stress may form an important part of your baseline assessment, particularly if you provide relaxation therapy or other stress management interventions. Initially, psychologists assessed stress in terms of the impact of certain life events (Holmes & Rahe 1967). The death of a spouse or close family member was deemed more severe in impact than holidays, a notable stressor. The number of stressful life events, particularly recent ones, is linked to health status and onset of health problems (Holmes & Rahe 1967).

More recently, assessment has focused on impact of daily hassles, i.e. acute events having a direct daily impact (Kanner et al 1981), particularly for people with chronic illnesses like RA (Treharne et al 2002, Turner Cobb et al 1998). When these events become long-term (e.g. daily difficulties at work due to hand problems; frequent tense exchanges with a relative due to their limited understanding of the impact of rheumatic disease), the stressor becomes chronic. The impact of daily hassles can possibly be worse than some of the major life events mentioned (Pillow et al 1996).

Global assessments of stress levels can also be used without addressing the specific event causing the stress. For example, the Perceived Stress Scale (Cohen et al 1983) is a short measure of whether an individual is failing to cope with their perceived stress. This has been applied in several rheumatic disease studies. Scores predict worsening of anxiety over one year (measured using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; Zigmond & Snaith 1983) among people with rheumatoid arthritis (Treharne et al 2007a).

Assessing potentially stressful events in your patients’ daily life can include the frequency, perceived impact and severity of the stressor for that individual. This can be measured with objective instruments, such as the Daily Stress Inventory (Brantley et al 1987). Alternatively, you can ask the patient to keep a simple daily diary of events and their responses (behaviours and moods) to help you design a tailored intervention to help them meet goals for improvement they set. Such diaries can be structured to cover various aspects of daily life (e.g. going shopping; when splints are used) in as much or as little detail as required. These do not have to meet psychometric standards necessary for research if being used as a clinical tool for information gathering, enabling the person to reflect on what they are experiencing on a day-to-day (or hour-by-hour) basis.

UNDERSTANDING STRESSORS

Common long-term daily stressors include frustration with daily activities, living with pain and fatigue and potentially limited understanding of family and friends. People with such long-term daily stressors may experience psychological and social changes that may be difficult to understand and accept (Katz & Neugebauer 2001). Health professionals need to respond to patient needs (which may not always be clearly articulated) and apply a range of approaches and models of self-care support. These approaches can be individual or group based. In order to target educational and therapeutic approaches appropriately we need to understand individual beliefs and capabilities, what knowledge patients have about their condition, the degree to which they have accepted their condition, their attitude, confidence and determination to achieve a progressive positive outcome (see Ch. 6).

COGNITIVE REPRESENTATIONS OF ILLNESS

As described earlier, cognitions are thought processes a person goes through to make sense of any situation or event. People form guides about what is expected in specific contexts, such as how to behave in a restaurant or lecture (e.g. not to throw food). These guides, called schemas, incorporate the norms and values appropriate to our society. However, people have individual beliefs and experiences that underpin the subtleties of their personal schemas (Greenberger & Padesky 1995).

Some well known illnesses have clear schemas, with labels attached to them, that people consider when searching for an explanation for a group of symptoms being experienced, for example ‘influenza’ (Bishop 1991). However, illnesses presenting with an array of rare, complex, variable and confusing symptoms are less easily interpreted. Individuals turn to other lay means of sense-making, for example, asking a relative or friend with a similar experience (Hale et al 2007). When it becomes necessary or apparent that formal medical assistance is required, diagnosis is not quick and the process may involve numerous tests and uncertainties. This can be common in rheumatic diseases, especially systemic lupus erythematosus (Hale et al 2006a), RA and fibromyalgia. This procedure contributes to the formation of patients’ beliefs, attitudes and uncertainties and subsequently updates their illness schemas (see Ch. 5). Leventhal and colleagues laid much of the groundwork for our understanding of illness perceptions (Nerenz & Leventhal 1983, see Leventhal et al 2003).

Different types of information influence different responses to perceived threats to health and well-being. Leventhal and colleagues explored what adaptations and coping efforts need to be made and maintained in people experiencing chronic illness. They proposed an adaptive system model in which illness representations guide coping responses and performance of action plans followed by monitoring of the success or failure of coping efforts (Nerenz & Leventhal 1983). The model has similarities with other problem-solving behaviour theories, such as the transactional model of stress and coping described earlier (Fig. 11.1), wherein chronic illness is conceptualised as the stressful experience (Lazarus & Folkman 1984). Leventhal and colleagues described parallel thinking about the illness danger (e.g. ‘What are these pains I keep getting, is there anything I can do about them?’) and emotional control (e.g. “I am upset as my doctor said she can’t cure it, what shall I do to make myself feel better about it?”) (Nerenz & Leventhal 1983).

MEASURING ILLNESS PERCEPTIONS

Validated questionnaire measures of illness perceptions include the Revised Illness Perception Questionnaire (Moss-Morris et al 2002, see Box 11.2) and a shortened version, the Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire (Broadbent et al 2006). These can be applied in clinical practice to access patients’ beliefs about their illness’s impact and future health. These impacts include assessments about its consequences, its controllability (by the individual as a self-manager or via treatments they are prescribed), its emotional impact and its coherence (i.e. whether the symptoms and overall illness experience make sense to the patient). Moss-Morris et al (2002) describe how the patient’s ongoing perceptions of the timeline of their illness relates to whether or not they think their illness will be permanent (i.e. chronic) and go through cycles (i.e. flare and remissions), as many rheumatic diseases can do (Hill & Ryan 2000).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree