Anterior Tibialis Transfer for Residual Clubfoot Deformity

Kenneth J. Noonan

DEFINITION

The incidence of residual deformity in congenital clubfoot ranges from 26.6% to 50%, regardless of the initial treatment provided.2

The disparity in the reported incidence is due to varying severity of clubfoot deformity, different methods of treatment, and, in part, differing definitions of residual deformity.

Residual deformities include isolated equinus, cavus, metatarsus adductus, hindfoot varus, forefoot supination, and combinations of the above.

Dynamic forefoot adduction and supination can be observed after clubfoot treatment with or without soft tissue releases.

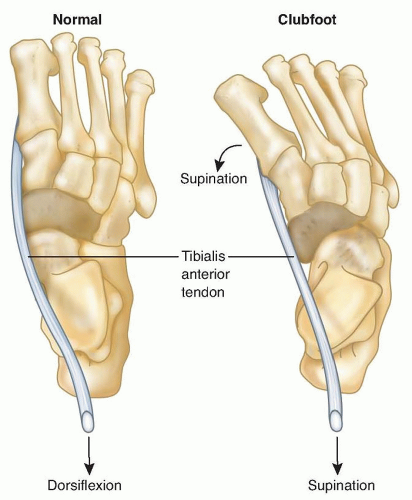

Dynamic forefoot supination deformity results from muscle imbalance. Anatomic imbalances can be due to primary absence or weakness of the anterior tibialis or peroneal muscles or as a result of neurologic abnormalities in the central nervous system or the peroneal nerve. Functional muscle imbalance can result from residual medial displacement of the navicular on the head of the talus. In this case, because its insertion is medially displaced, the anterior tibialis becomes a forefoot supinator instead of a dorsiflexor (FIG 1).

The aim of treatment is to correct any fixed deformity and to rebalance the muscles of the foot, thereby correcting dynamic deformity and improving foot alignment.

ANATOMY

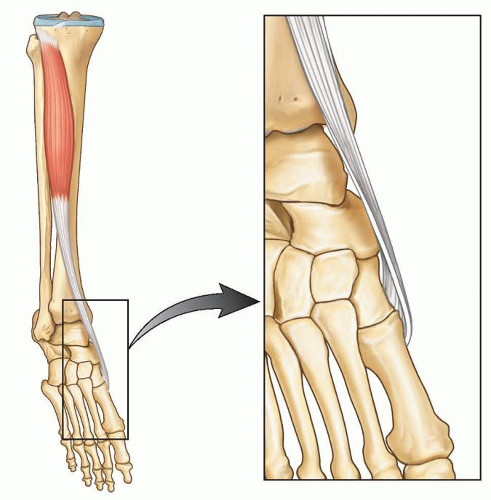

The anterior tibialis muscle originates from the upper two-thirds of the tibia.

The anterior tibialis tendon fibers rotate 90 degrees from the musculotendinous junction to its insertion on the medial cuneiform and first metatarsal.

Medial rotation begins proximally, so the most medial muscle fibers proximally rotate to the posterior surface of the tendon near the midpoint and continue to rotate so that their final insertion is as the distal-lateral fibers on the first metatarsal.

Meanwhile, the most lateral muscle fibers proximally rotate to the anterior surface at the midpoint and continue distally to insert on the cuneiform as the proximal-medial fibers (FIG 2).4

The anterior tibialis muscle is active in two important stages of the gait cycle; it concentrically fires during the initiation of swing phase and keeps the foot dorsiflexed during early swing phase and then it relaxes. The anterior tibialis muscle then fires eccentrically as the foot is lowered to the floor from heel strike to foot flat in stance phase.

As a dorsiflexor, the anterior tibialis muscle opposes gravity and the strong gastrocsoleus complex. Importantly, the anterior tibialis muscle may also be a supinator of the forefoot in the face of peroneal longus weakness or medial displacement of the insertion.

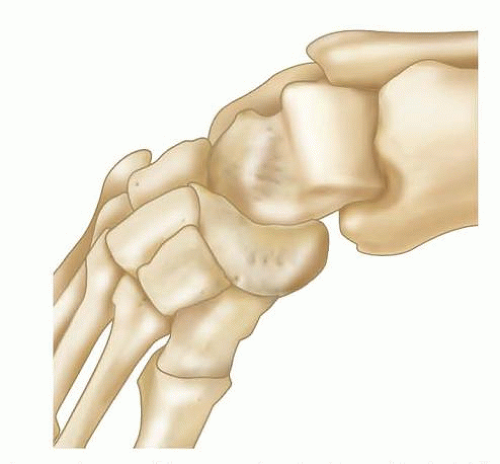

There are important bony abnormalities associated with residual clubfoot deformity.

The subtalar joint may have an absent anterior facet and small, narrow medial and posterior facets, resulting in restricted subtalar motion. In this setting, the calcaneus does not slide fully into valgus with casting such that the navicular remains medially displaced.

PATHOGENESIS

The cause of residual clubfoot deformity may be incomplete correction or recurrence of deformity as part of the natural history of the resistant clubfoot.

Electromyographic and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies have demonstrated that the peroneal muscle group can be absent, smaller, and relatively weaker, thus increasing the supinator action of the tibialis anterior muscle.1, 3

Medial subluxation of the navicular is considered an important factor influencing both the appearance of the foot and the lateral rotation of the ankle.9

In addition to the bony abnormalities associated with clubfeet, anatomic variations from the customary insertion of the anterior tibialis muscle into adjacent areas of the first metatarsal and medial cuneiform occur in 10% of pathologic specimens.

In these variants, the distal anterior tibialis muscle inserts more medially than normal, optimizing the force vector for supination.8

FIG 3 • Bony abnormalities associated with residual clubfoot deformity. The navicular is wedge-shaped and is medially displaced along with the cuneiforms and metatarsals.

NATURAL HISTORY

Residual deformities are usually encountered within the first year after initial treatment and generally before the age of 5 years, even in congenital clubfeet that had been fully corrected since the first month of life.

Residual forefoot adduction and supination are common deformities after nonoperative treatment and can also be seen after initial operative repair. They can result from undercorrection at the time of the primary intervention.13

Correction of resistant congenital clubfoot often requires more than one surgery, not because of a “failed initial intervention,” but because the dynamic muscle imbalances may not be fully manifest at the time of the initial intervention. Thus, the need for an additional operation can be perceived as part of the natural history of congenital clubfoot.12

If left untreated, the dynamic deformity may become stiff and the foot tends to invert.

When inversion deformity is combined with residual equinus deformity, hindfoot varus may recur (FIG 4).

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Residual deformity is more likely in patients who have clubfoot as a result of myelomeningocele or other neuromuscular syndromes and genetic disorders such as Larsen syndrome. Therefore, it is important to consider neurologic causes, such as tethered cord, when confronted with residual deformity.

Recurrent deformity may be found in children with only four toes on the affected foot, as these individuals may have absence of the peroneal muscle group (similar to that seen in fibular hemimelia), thus leaving them prone to recurrence.

Recurrent deformity may be suspected prior to treatment in newborns with curled toes and no active toe dorsiflexion when scratching the plantar aspect of the foot. In those infants that have been treated with the Ponseti method, later recurrence may be heralded by scratching the bottom of the foot that leads to more supination than dorsiflexion.

One of the first clinical signs of recurrence is a dynamic inversion of the foot with slight equinus. Equinus may be difficult to quantify, as midfoot breech will often accommodate and hide the hindfoot equinus (FIG 5).

Residual deformity most frequently occurs in severe or atypical cases, which are often associated with a small calf size. These children may also have short, fat feet with a deep plantar crease that extends from the medial border

to the lateral border of the foot and a shortened first ray. These findings are consistent with severe or atypical clubfeet (often termed complex clubfoot) that have a propensity for residual deformity.

In maximum pronation or maximum supination, the navicular-medial malleolar distance is decreased compared to the normal foot. In fact, the medial malleolus can be difficult to delineate because it is in contact with the navicular. The navicular malleolar distance demonstrates the extent of medial subluxation.

It is important to examine gait when possible.

During examination of gait, the clinician should identify whether the tibialis anterior is a dynamic supinator; this is best observed in swing phase when no antagonist muscles contract.

This finding will confirm the appropriateness of surgery.

The strength of the tibialis anterior is tested. With dynamic supination deformity, the supinator action of the anterior tibialis muscle will overpower the dorsiflexor action, thus demonstrating the appropriateness of surgery. In addition, good power is needed for a successful transfer.

The clinician should evaluate for other deformities, such as equinus, cavus, varus, adductus, and tibial torsion.

Range of motion of the ankle is examined. Transfer will work only as long as there is no fixed contracture of the ankle or heel cord.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Anteroposterior (AP) and lateral radiographs may be helpful to study and quantify various deformities.

AP radiographs will demonstrate medial deviation of the metatarsals, which can indicate residual medial displacement of navicular, which is yet to ossify (FIG 6).

On an AP radiograph of normal feet, the line drawn through the long axis of the talus should point to the first metatarsal, whereas the line drawn through the long axis of the calcaneus should point toward the fourth metatarsal.

In clubfeet, these lines become more parallel, depicting “stacking” of the talus and calcaneus.

Forced maximum dorsiflexion lateral radiographs may reveal hindfoot equinus with midfoot breech.

Stacking of the metatarsals on the lateral radiograph identifies the presence of residual forefoot supination (a decreased talocalcaneal angle).

Ultrasound evaluation of the foot is not done routinely. However, experimental studies have demonstrated that this technique is capable of documenting the location of the navicular in relationship to the head of the talus. The navicular is subluxated plantarward and medially on the head of the talus.

Similarly, MRI can be performed to completely identify the relationships of the cartilaginous bones and the size and presence of the lateral leg muscles.

This technology is rarely clinically used, as orthopaedists are aware of the classic deformities that are associated with recurrence and the increased risk of general anesthesia for a childhood MRI scan may not be justified.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Residual deformities in clubfoot may be due to unrecognized tarsal coalitions or other conditions in syndromic clubfoot, severe, or complex clubfeet.

Unexpected and rapid recurrent deformity in children with previously corrected feet and with known myelomeningocele may be a result of continued neurologic involvement, such as tethering of the spinal cord.

FIG 6 • Weight-bearing AP and lateral radiographs of feet shown in FIG 5. A. The long axes of the talus and calcaneus are somewhat parallel rather than divergent. The metatarsals appear adducted in relation to the talus. B,C. The long axis of the talus and calcaneus appear somewhat parallel rather than divergent on the lateral view of the right foot. The axes of the talus and the first metatarsal do not form a straight line, as opposed to a normal foot. This degree of divergence from this linear alignment represents intrinsic deformity of the clubfoot. The metatarsals are stacked on the weight-bearing lateral views.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access