Anterior Superior Rotator Cuff Tears: Repairable and Irreparable Tears

T. Bradley Edwards

Gilles Walch

Laurent Nové-Josserand

Christian Gerber

T. B. Edwards: Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, University of Minnesota.

G. Walch: Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, University of Lyon, France.

L. Nové-Josserand: Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, University of Lyon, France.

C. Gerber: Department of Orthopaedics, University of Zurich, Balgrist, Switzerland.

INTRODUCTION

Shoulder pathology specifically involving the anterior superior rotator cuff is becoming more recognized predominantly because of increasing surgeon awareness. It is now better understood that lesions affecting this part of the rotator cuff are distinct entities that behave differently than the more commonly recognized lesions of the posterior superior rotator cuff. The frequent involvement of the rotator interval and the long head of the biceps tendon mandates that these lesions be treated differently than those lesions limited to the posterior superior rotator cuff.

Tears of the anterior superior rotator cuff are defined as those involving any aspect of the subscapularis tendon and may involve lesions of the supraspinatus tendon. Additionally, because of their anatomic proximity, anterior superior rotator cuff lesions are frequently coupled with pathology of the rotator interval (superior glenohumeral ligament [SGHL], coracohumeral ligament [CCHL]), and the long head of the biceps tendon. This chapter will provide an overview of anatomy, epidemiology, clinical evaluation, and imaging of anterior superior rotator cuff lesions. Additionally, this chapter will detail our preferred treatment and provide data regarding expected outcomes of treatment of anterior superior rotator cuff tears.

NORMAL ANATOMY

The rotator cuff is a continuous tendinous band that is intimately connected with the glenohumeral articular capsule. It can be divided into three parts: the posterior cuff with the infraspinatus tendon and the teres minor tendon; the superior cuff with the supraspinatus tendon; and the anterior cuff with the subscapularis tendon and the rotator interval. The rotator interval also includes the intra-articular portion of the tendon of the long head of the biceps.

The subscapularis muscle originates in the subscapularis fossa of the scapula. The muscle inserts via a strong tendon on the superior medial aspect of the lesser tuberosity. Many fibers of the subscapularis tendon extend laterally and superiorly to form the medial wall of the bicipital groove and merge with the supraspinatus tendon. The subscapularis tendon and the supraspinatus tendon are thereby intertwined for approximately 1 cm before inserting into the lesser and greater tuberosity, respectively. Inferiorly, the subscapularis tendon becomes less substantial so that its inferior most insertion is almost purely muscular.

The supraspinatus muscle originates in the supraspinatus fossa of the scapula superior to the scapular spine. The muscle inserts via a strong tendon on the superior facet of the greater tuberosity. Many fibers of the supraspinatus tendon extend medially to form the lateral wall of the bicipital groove and merge with the subscapularis tendon.

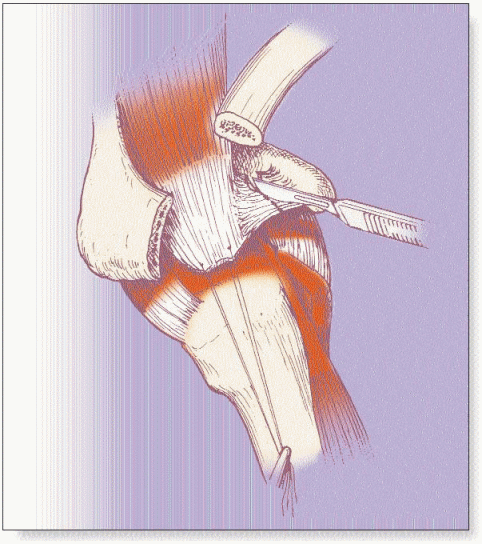

The rotator interval is composed of the coracohumeral ligament, the superior glenohumeral ligament, the joint capsule, and expansions of the subscapularis and supraspinatus tendons. The coracohumeral ligament is the dominant structure of the rotator interval (Fig. 6-1). It bridges the subscapularis and the supraspinatus tendons and ensures continuity of the rotator cuff. It is triangular, with its base at the coracoid, its apex over the bicipital groove, one side inserting mainly into the greater tuberosity, and one side inserting mainly into the lesser tuberosity. It becomes intimately associated with the glenohumeral joint capsule and covers the long head of the biceps tendon.

The superior glenohumeral ligament originates variably from the anterior superior neck of the scapula, either from the cartilaginous labrum, from the osseous scapular neck, or both. It lies deep to the coracohumeral ligament, and at its origin, is separated from it by fatty tissue (Fig. 6-1). Laterally, the superior glenohumeral ligament becomes intertwined with the portion of the coracohumeral ligament that inserts proximal to the tendon of the subscapularis immediately adjacent to the bicipital groove on the lesser tuberosity. Deep fibers from the superior glenohumeral ligament and coracohumeral ligament line the floor of the bicipital groove. These structures (the subscapularis tendon, the coracohumeral ligament, and the superior glenohumeral ligament) are closely related and form a reflection pulley complex that functions as a stabilizer for the long head of the biceps centering it within its groove.21

The long head of the biceps tendon takes origin at the supraglenoid tubercle of the scapula. It traverses horizontally over the humeral head reaching the entrance of the bicipital groove where it becomes vertical and extra-articular. Rotation and abduction change the position of the intra-articular portion of the long head of the biceps. As the arm is externally rotated the long head of the biceps translates medially around the curvature of the humeral head, placing increased forces on the medial stabilizing structures as they attempt to maintain the long head of the biceps within the bicipital groove. The ligamentous pulley complex plays a major role in stabilizing the long head of the biceps because insufficient stability is imparted by the osseous constraints of the groove. Hence, the structural integrity of the ligamentous pulley system is mandatory for stability of the long head of the biceps.

PATHOLOGY

For the purposes of this chapter, lesions will be discussed in one of the following categories: isolated lesions of the subscapularis tendon, lesions of the subscapularis and supraspinatus tendons, or associated lesions of the rotator interval and long head of the biceps tendon.

Isolated Lesions of the Subscapularis Tendon

Most subscapularis lesions involve the superior lateral insertion of the tendon at its insertion on the lesser tuberosity. These lesions progress in a medial and inferior direction. The tendon is commonly avulsed directly from bone rather than torn in its midsubstance. Lesions originating at the inferior aspect of the subscapularis tendon have been described but are exceptionally rare. Isolated lesions of the

subscapularis tendon can be categorized based on relative size: lesions of the superior third of the subscapularis tendon, lesions of the superior two-thirds of the subscapularis tendon, and complete lesions of the subscapularis tendon.

subscapularis tendon can be categorized based on relative size: lesions of the superior third of the subscapularis tendon, lesions of the superior two-thirds of the subscapularis tendon, and complete lesions of the subscapularis tendon.

Superior third lesions of the subscapularis tendon represent an avulsion from the lesser tuberosity. If the ligamentous pulley complex is intact, this lesion is not visible during gross inspection of the rotator cuff. If the ligamentous pulley complex is divided, this type of lesion is identified as a bare area of bone at the superior aspect of the lesser tuberosity. The humeral insertion of the superior glenohumeral ligament may be intact or torn. Minimal tendinous retraction occurs with this type of tear because the inferior two-thirds of the subscapularis tendon remain intact.21

Lesions of the superior two-thirds of the subscapularis tendon leave only the inferior muscular insertion intact. With this type of lesion the subscapularis tendon is absent over the entire surface of the lesser tuberosity. In approximately one-half of the cases, this type of tear is not immediately visible during initial open surgical exploration because the lesser tuberosity is obscured by scar tissue hiding the lesion.7 Tendinous retraction varies according to the extent and chronicity of the lesion.

Complete lesions of the subscapularis consist of an avulsion of both the tendinous and muscular insertions of the subscapularis from the lesser tuberosity. This often occurs with retraction of the musculotendinous unit beyond the glenoid rim into the subscapularis fossa and may result in significant muscular atrophy and fatty degeneration observed on computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). In younger patients, a midsubstance tendinous rupture with a lateral tendinous stump may be observed in contrast to the typical avulsion from bone.

Lesions of the Subscapularis and Supraspinatus Tendons

A second type of anterior superior rotator cuff lesion involves the supraspinatus tendon, in addition to the subscapularis tendon. In this scenario, tears involving the subscapularis may be classified in much the same way as in isolated lesions of the subscapularis: superior third, superior two-thirds, or complete. Tears of the supraspinatus are usually a superior extension of the subscapularis tear and, hence, preferentially involve the anterior aspect of the supraspinatus tendon. These tears are thought to propagate in a posterior direction and may involve the entire width of the supraspinatus tendon or even extend to involve the infraspinatus tendon.

Lesions of the Rotator Interval and Long Head of the Biceps Tendon

Lesions of the rotator interval and the long head of the biceps tendon are intimately associated with tears of the anterior superior rotator cuff by virtue of their anatomic locale. Tears of the anterior superior rotator cuff invariably lead to some degree of secondary biceps tendinitis. Biceps tendinitis is a term to describe an alteration in the structure of the tendon and may be atrophic, hypertrophic, frayed, or inflammatory.21

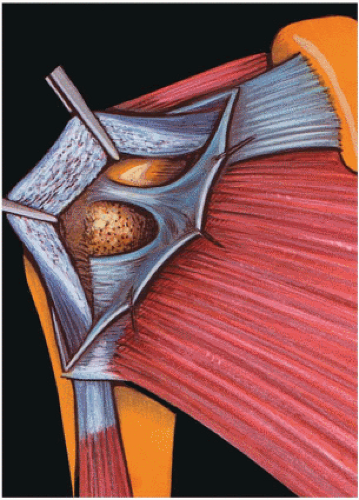

Pathology of the anterior superior rotator cuff represents the most common cause of biceps tendinitis and can be classified by the type of underlying lesion. Lesions of the subscapularis can cause inflammation and distension of the ligamentous pulley and bicipital sheath, ultimately destabilizing the biceps within its groove (Fig. 6-2). Degeneration and tearing limited to the rotator interval (coracohumeral ligament and superior glenohumeral ligament) can result in inflammation of the biceps tendon and fraying of its superior aspect from mechanical friction of the tendon against the coracoacromial arch.

Large tears of the rotator cuff, including disruption of the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and rotator interval, invariably lead to some degree of biceps disease. Once the infraspinatus is disrupted, proximal migration of the humeral head

ensues, entrapping the biceps tendon between the humeral head and coracoacromial arch, resulting in mechanical abrasion of the tendon with anterior elevation of the arm.

ensues, entrapping the biceps tendon between the humeral head and coracoacromial arch, resulting in mechanical abrasion of the tendon with anterior elevation of the arm.

Anterior superior rotator cuff tears with associated rotator interval lesions frequently result in instability of the biceps tendon, in addition to structural changes within the tendon. Instability can occur as subluxation, a transitory or partial loss of contact between the biceps tendon and the bicipital groove, or dislocation, fixed or complete loss of contact between the biceps tendon and the bicipital groove.20 Biceps subluxation generally occurs in a medial direction via disruption or distension of the ligamentous pulley complex, resulting in fraying of the medial aspect of the biceps tendon.

Dislocation of the biceps tendon can occur with the tendon resting on the lesser tuberosity (partial tear of the subscapularis), the tendon dislocated intra-articularly (complete rupture of the subscapularis), or with the tendon dislocated extra-articularly and resting on the anterior surface of the subscapularis (subscapularis intact, disruption of the rotator interval). When the tendon is resting on the lesser tuberosity, mechanical friction on the tendon will evolve to spontaneous rupture. With complete intra-articular or extra-articular dislocation, absence of mechanical friction often prevents spontaneous rupture.

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of lesions affecting the anterior superior rotator cuff can be difficult, particularly in the case of small lesions limited to the superior portion of the subscapularis tendon and rotator interval. Diagnosis of these lesions requires proper examination and use of appropriate imaging studies.

Epidemiology

Although both sexes are affected, lesions of the anterior superior rotator cuff predominantly affect men. The dominant arm is involved in most cases. In our experience a history of trauma is associated with the onset of symptoms in about 85% of patients. If a trauma involving external rotation and extension of the arm or anterior traumatic dislocation is reported by a patient older than 40 years of age, a subscapularis lesion should be suspected. In cases of less extensive involvement of the subscapularis, there is often little or no trauma. These atraumatic lesions appear to be degenerative in origin.

Clinical History

Three types of presentations are characteristic: chronic and progressive shoulder pain following a traumatic event, pseudoparalytic shoulder, and pain with shoulder stiffness. Roughly, one-half of the patients seek medical advice for chronic and progressively increasing shoulder pain after a defined traumatic event. Pain is constant and aggravated by using the arm at the side or above the head. Night pain is also a common feature. The pattern of pain is not distinctly different from that of isolated supraspinatus tears, with the exception that the patient with a large anterior lesion may also report aggravation of pain with the use of the arm below shoulder level.

Approximately one-third of patients present with a pseudoparalytic shoulder. Passive range of motion is preserved, but active elevation is limited to less than 90 degrees. Pseudoparalysis is typically associated with large multiple tendon rotator cuff tears. Shoulders with pain and stiffness (decrease of active and passive range of motion) are rare. Pain and stiffness are not specific for any type of lesion or severity of injury.

A fourth subset of patients exists with asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic subscapularis tears. These patients are often seen by a physician for another problem and mention their shoulder in passing or may have an acute injury superimposed on a chronic minimally symptomatic subscapularis tear. These tears are generally best left untreated.

Clinical Examination

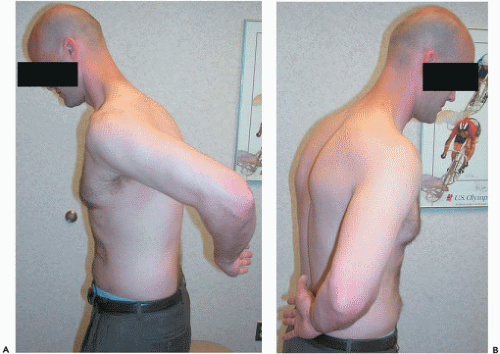

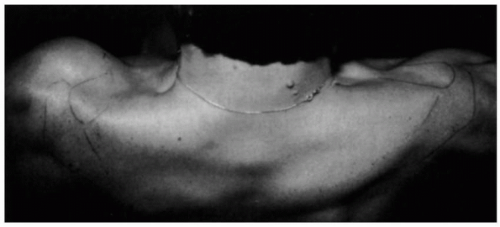

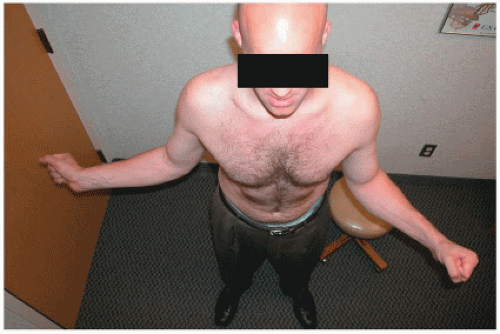

A thorough shoulder examination should include active and passive ranges of motion. Standard clinical strength testing of the rotator cuff is performed. Of the tests specifically evaluating the anterior superior rotator cuff, Jobe’s test is employed to evaluate supraspinatus integrity.10 Subscapularis involvement is documented with three observations. Increased passive external rotation with the arm at the side is a specific sign for complete subscapularis disruption, provided the contralateral shoulder is normal (Fig. 6-3). The lift-off sign is tested with the arm passively brought into maximal internal rotation behind the

patient’s body.7 The examiner asks the patient to maintain the position of maximal internal rotation by holding the hand off the back. If this is possible, the subscapularis is largely intact. If the patient cannot maintain this position and the hand drops back toward the back, the test is positive, indicating pathology of the subscapularis (Fig. 6-4). In the complete tear, the hand cannot be held off the back in any capacity, but in partial lesions, the hand may drop toward the back but without dropping to rest on the back. The lift-off sign is less useful in patients experiencing extreme pain with internal rotation and in patients with stiffness, which prevents adequate internal rotation for the test. The belly-press test is positive when the patient is required to flex the wrist and extend the arm to exert force on the lower abdomen with the affected upper extremity (Fig. 6-5). Although the use of clinical tests to detect ruptures of the subscapularis has been extremely reliable for some examiners, partial tears of the subscapularis remain more difficult to diagnose than complete tears and may present only with isolated weakness in internal rotation.

patient’s body.7 The examiner asks the patient to maintain the position of maximal internal rotation by holding the hand off the back. If this is possible, the subscapularis is largely intact. If the patient cannot maintain this position and the hand drops back toward the back, the test is positive, indicating pathology of the subscapularis (Fig. 6-4). In the complete tear, the hand cannot be held off the back in any capacity, but in partial lesions, the hand may drop toward the back but without dropping to rest on the back. The lift-off sign is less useful in patients experiencing extreme pain with internal rotation and in patients with stiffness, which prevents adequate internal rotation for the test. The belly-press test is positive when the patient is required to flex the wrist and extend the arm to exert force on the lower abdomen with the affected upper extremity (Fig. 6-5). Although the use of clinical tests to detect ruptures of the subscapularis has been extremely reliable for some examiners, partial tears of the subscapularis remain more difficult to diagnose than complete tears and may present only with isolated weakness in internal rotation.

Figure 6-3 Increased external rotation of the shoulder with the arm at the side in a patient with a complete subscapularis disruption. |

Dynamic anterior superior subluxation of the humeral head associated with active elevation of the arm indicates a large tear of the subscapularis and supraspinatus tendons (Fig. 6-6). The patient performs resisted abduction with the examiner observing from behind. Dynamic subluxation occurs during the initial degrees of abduction and may occasionally be palpated under the deltoid rather than be observed.

Pathology involving the long head of the biceps remains an enigma to clinical diagnosis. Although most completely ruptured biceps are easily detectable on clinical examination by the ball-like deformity of the biceps muscle belly present when the arm is elevated to 90 degrees and the elbow is forcibly flexed, more subtle bicipital problems are difficult to diagnose. The palm-up test can be performed with the elbow extended and the forearm supinated. The

patient is asked to elevate the arm against resistance (Speed’s test). If pain is elicited along the anterior part of the biceps, the test is positive,. Although other tests have been described (Yergason’s test, O’Brien’s test), in our experience, none of these tests have been found to be very specific for bicipital lesions. Similarly, dislocation or subluxation of the biceps cannot be reliably detected clinically. A slight clicking sound perceived by the patient and the examiner during rotation is uncommon and may or may not be caused by biceps dislocation.

patient is asked to elevate the arm against resistance (Speed’s test). If pain is elicited along the anterior part of the biceps, the test is positive,. Although other tests have been described (Yergason’s test, O’Brien’s test), in our experience, none of these tests have been found to be very specific for bicipital lesions. Similarly, dislocation or subluxation of the biceps cannot be reliably detected clinically. A slight clicking sound perceived by the patient and the examiner during rotation is uncommon and may or may not be caused by biceps dislocation.

Similar to the long head of the biceps, pathology of the rotator interval can be difficult to diagnose on clinical examination. A compromised coracohumeral ligament and/or SGHL can only be suspected clinically in patients

with abnormal joint laxity. If a positive inferior drawer test in neutral rotation (sulcus sign) does not diminish in external rotation, a lesion of the rotation interval is suspected.

with abnormal joint laxity. If a positive inferior drawer test in neutral rotation (sulcus sign) does not diminish in external rotation, a lesion of the rotation interval is suspected.

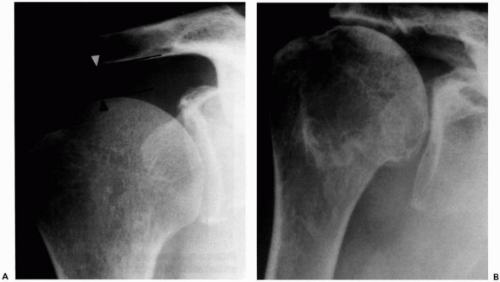

Imaging

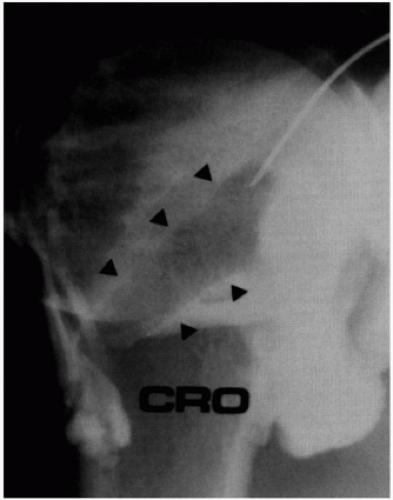

Conventional radiography includes anterior posterior views in neutral, internal rotation, and external rotation; a lateral view in the scapular plane; and an axillary view (Fig. 6-7). Ideally, radiography is performed under fluoroscopic and magnification control. The subacromial space between the inferior cortex of the acromion and the humeral head is measured on the anterior posterior neutral rotation view. A subacromial space less than 7 mm indicates an extensive rotator cuff tear involving the posterior rotator cuff (infraspinatus). Cystic lesions or sclerosis of the lesser tuberosity suggest an anterior rotator cuff lesion. Anterior subluxation is often not readily identifiable using conventional radiography, although it may be suspected on axillary views.

Arthrography coupled with subsequent CT is an excellent advanced imaging modality for exploring the anterior superior rotator cuff. Use of a radiopaque contrast medium provides more reliable imaging than air or double-contrast arthrography. Arthrography, performed immediately prior to CT, should include imaging during the injection of the contrast using multiple views. Contrast extravasation into the subacromial bursa is diagnostic of a full thickness rotator cuff tear, which can then be more precisely localized from the various rotational and lateral views.

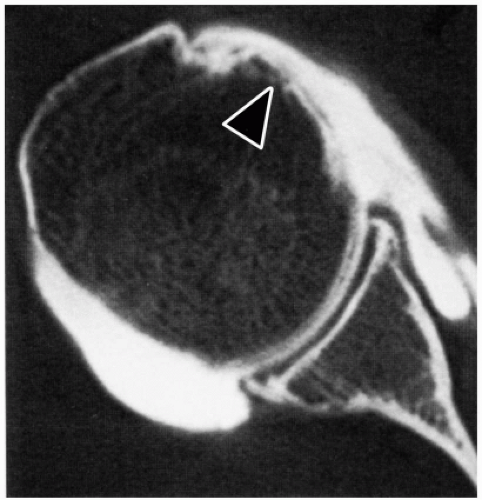

A subscapularis lesion is suspected if contrast reaches the lesser tuberosity on the anterior posterior view in neutral and, more specifically, in external rotation. This sign, which may be subtle, is positive in 80% of patients with a subscapularis tear. This finding, however, is not apparent in partial ruptures of the superior subscapularis tendon. Failure to visualize the bicipital groove is pathognomonic for a biceps lesion and suspicious for an anterior rotator cuff lesion. This finding, however, is not indicative of the type of biceps lesion, unless the long head of the biceps tendon is visualized medial to the bicipital groove, confirming dislocation (Fig. 6-8). Rupture of the long head of the biceps is confirmed when the bicipital groove is filled with contrast rather than with the tendon.

Although arthrography is useful in the diagnosis of anterior superior rotator cuff lesions, we rarely employ it without a postarthrography computed tomogram. Computed tomographic arthrography offers great diagnostic and prognostic value, allowing diagnosis of subscapularis and long head of the biceps tendon abnormalities, providing an anatomic outline of the subcoracoid space and of

articular congruence, and allowing evaluation of fatty degeneration of the rotator cuff musculature.

articular congruence, and allowing evaluation of fatty degeneration of the rotator cuff musculature.

Figure 6-8 Arthrography of the shoulder demonstrating dislocation of the long head of the biceps tendon (arrows) and full thickness rotator cuff rupture. |

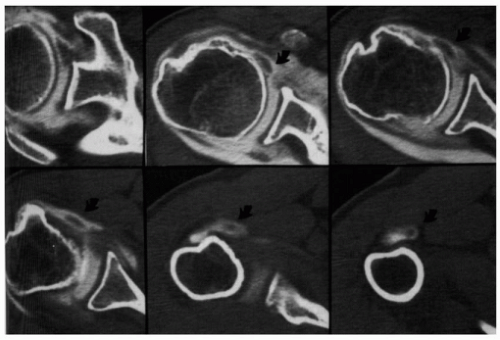

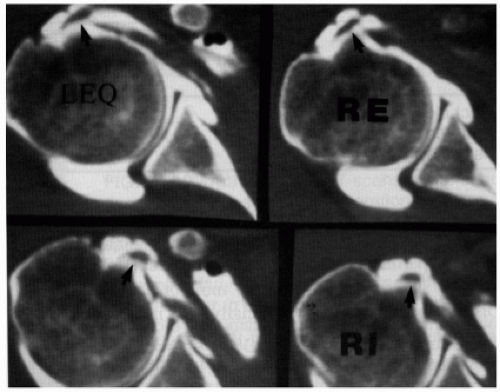

Lesions of the subscapularis tendon are demonstrated by the presence of contrast in contact with the bony surface of the lesser tuberosity, where the subscapularis tendon normally inserts (Fig. 6-9). The size of the lesion is determined by the number of computed tomographic sections on which it is visible. This sign may be difficult to see in very small partial thickness superior lesions or in the rare case of midsubstance tendon rupture.

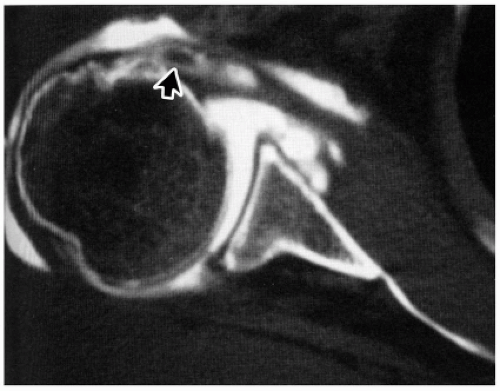

Dislocation and subluxation of the long head of the biceps tendon are readily identifiable using computed tomographic arthrography (Fig. 6-10). The examiner must be wary of erroneous interpretation of dislocation of the long head of the biceps tendon at the inferior aspect of the groove. This finding is usually the result of recentering of the dislocated tendon, which occurs when the superior part of the subscapularis tendon has ruptured and dye reaches inferiorly into the bicipital groove over the inferior part of the subscapularis muscle fibers that normally insert at the inferior aspect of the lesser tuberosity (Fig. 6-11). Subluxation of the biceps is diagnosed when the biceps is perched on the medial aspect of the lesser tuberosity. The long head of the biceps has the shape of a comma and runs along the medial wall of the bicipital groove (Fig. 6-12). Subluxation and dislocation of the long head of the biceps virtually always occur with a subscapularis tendon tear. The exception is the rare case in which the biceps is dislocated anterior to an intact subscapularis through a disruption in the rotator interval. Rupture of the long head of the biceps tendon is diagnosed, if the bicipital groove is void and the tendon cannot be visualized intra-articularly (Fig. 6-9).

Figure 6-10 Computed tomographic arthrogram of the shoulder. The arrow indicates a dislocated long head of the biceps tendon. |

Gerber et al.6 examined the morphology of the subcoracoid space and its potential role for the development of anterior rotator cuff lesions. In a control series of 47 shoulders, the distance between humeral head and tip of the coracoid averaged 8.7 mm with the internally rotated arm at the side and 6.8 mm with internally rotated arm at 90 degrees of elevation. In 40 shoulders with anterior superior rotator cuff lesions, the average coracohumeral distance averaged 8.1 mm, and, in one-third of the cases, it was less than 6 mm. Lesions of the subscapularis tendon and dislocation of the long head of the biceps tendon were related to a diminished coracohumeral distance. The coracohumeral space became narrower with increasing severity of the subscapularis lesion. The coracohumeral distance averaged 10.6 mm for superior one-third lesions, 7.6 mm for superior two-thirds lesions, and 6.8 mm for complete lesions of the subscapularis. Dislocation of the biceps, especially if intra-articular, is coupled with a reduction of the coracohumeral distance. In some cases, anterior subluxation of the humeral head will lead to glenohumeral static subluxation and coracohumeral contact (coracohumeral impingement; Fig. 6-13).

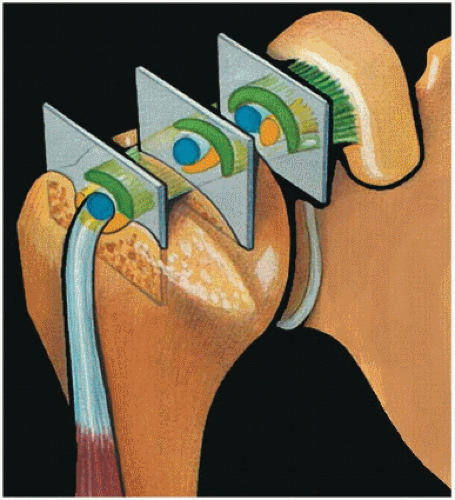

The degree of fatty infiltration and degeneration of the rotator cuff musculature are major prognosticators of treatment results for rotator cuff tears. Goutallier et al.8 first recognized this phenomenon using CT of the rotator cuff muscle bellies. Fatty degeneration is classified for each of the rotator cuff muscles: stage 0, characterized by normal muscle and absence of fat; stage 1, characterized by minimal fatty infiltration; stage 2, characterized by less fat than muscle; stage 3, characterized by as much fat as muscle; and stage 4, characterized by more fat than muscle. This classification scheme is depicted in Figure 6-14. It should be emphasized that muscle degeneration assessment is a qualitative analysis of the muscle and does not reflect muscle atrophy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree