Anterior Shoulder Stabilization

Brian T. Feeley

Benjamin C. Ma

INTRODUCTION

Anterior shoulder instability is one of the most common injuries about the shoulder and accounts for one third of all emergency cases related to the shoulder. Recurrence is common and is directly related to the age of the patient. Some studies have found anterior instability to recur in >80% of patients younger than 20 years of age (19). Recurrence rates decrease to <50% by the time the patient reaches 30 years of age (18).

The treatment of patients with a traumatic first-time anterior shoulder dislocation is somewhat controversial. Some authors advocate surgical stabilization immediately, especially in young athletes (13). Others recommend nonoperative management with an emphasis on physical therapy and rehabilitation. However, the preferred treatment of a patient who has undergone multiple anterior shoulder dislocations is usually surgical, as the risk for articular and bony damage increases with subsequent dislocations.

The gold standard for anterior stabilization procedures remains the open Bankart procedure for anatomic reconstruction of the anteroinferior labrum. Arthroscopic techniques, originally described by Caspari and Morgan, have gained acceptance as the primary surgical treatment option in patients with recurrent anterior shoulder dislocations and no loss of the anteroinferior glenoid—the so-called Bony Bankart lesion. Early results with tacks and transglenoid sutures were less than promising, with recurrence rates ranging from 20% to 43% (10,11).

Newer arthroscopic techniques including suture anchor fixation and capsulolabral repair have increased the success rates of arthroscopic anterior shoulder stabilization to the level of an open Bankart repair in many series (5). Current techniques are highly reproducible and allow for consistent outcomes in the hands of an experienced shoulder surgeon.

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

The indications for surgical treatment of anterior shoulder instability include patients who have had more than one traumatic dislocation and patients with a single traumatic dislocation but continue to have symptoms of instability or subtle subluxation despite a trial of physical therapy. The indications for arthroscopic anterior stabilization are as follows (7):

Noncontact athlete under the age of 30

Acute, traumatic injury

Presence of a Bankart lesion on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Normal laxity on physical exam

Well-developed inferior glenohumeral ligament complex

Open surgical stabilization is considered the optimal treatment in select cases (7):

Significant glenoid bone loss

Significant humeral bone loss

Capsular deficiency

Humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligament (HAGL lesion)

Failed prior arthroscopic management

However, as arthroscopic techniques continue to improve, the indications for arthroscopic rather than open stabilization have been expanding. Some surgeons will consider revision arthroscopic stabilization, and treatment of a HAGL lesion can be performed arthroscopically as well (17,20). It remains controversial as to how to treat

contact athletes. Although many surgeons will perform an arthroscopic stabilization, the rate of recurrence has been shown to be higher in this patient population (6,15).

contact athletes. Although many surgeons will perform an arthroscopic stabilization, the rate of recurrence has been shown to be higher in this patient population (6,15).

Contraindications for undergoing surgical stabilization include recurrent voluntary dislocators, multidirectional instability, and patients who are poorly motivated or unable to comply with the postoperative treatment program.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

History

As with any orthopaedic problem, the first step toward a diagnosis is a thorough history. For anterior shoulder instability, the mechanism of injury should be obtained in order to determine if the injury was of high energy or low energy. Patients with lower-energy dislocations may have a component of excess laxity and should be evaluated accordingly. The patient is asked if the shoulder subluxed or truly dislocated, and whether they were able to reduce the shoulder on their own or if it required anesthesia to achieve reduction. Clearly, the most important question to ask is if this dislocation was the first dislocation, and if not, how many previous dislocations have occurred on the affected shoulder.

Examination

Physical exam of the shoulder begins with visual inspection of the shoulder girdle. The contour of the deltoid should be evaluated to assess for an axillary nerve injury, which is an uncommon but reported complication following a shoulder dislocation. Range of motion is assessed and is typically normal. Isometric testing of the rotator cuff is performed. A rotator cuff tear is unlikely in a young patient with anterior instability; however, there is increasing frequency of rotator cuff tears as the patient ages. The apprehension sign, which is performed by bringing the arm into the abduction and external rotation position, is typically quite positive following a recent dislocation. The relocation test is likewise positive in most patients with anterior instability. A load and shift test can be performed in the office setting as well, but it may be difficult for the patient to relax enough to determine the correct amount of instability. The sulcus sign is performed by pulling down on the arm with the patient in a seated position. When positive, there is increased translation between the acromion and the humeral head, suggesting laxity in the rotator interval. In patients with suspected multidirectional instability, the sulcus sign is usually positive; other joints should be evaluated for signs of generalized ligamentous laxity.

Imaging

We typically obtain a true AP view of the shoulder, an axillary view, a scapular Y view, and a stryker-notch view. Bony Bankart lesions are best assessed on the true AP of the shoulder and the axillary view of the shoulder.

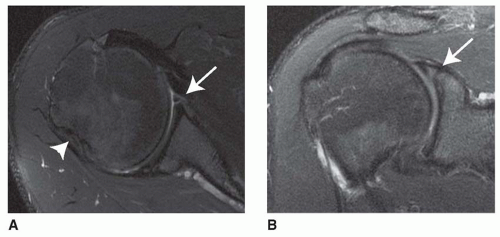

A Hill-Sachs lesion is best seen on the Stryker-notch view. MRI has become the gold standard for the diagnosis of anterior labral tears. It is particularly useful in determining concomitant pathology such as superior labral tears, biceps lesions, and posterior labral tears. It is also helpful in determining if the instability is due to a Bankart lesion or a HAGL lesion, which would alter the operative plan considerably. In our institution, we use contrast enhanced MR arthrograms for shoulder dislocations more than 3 weeks old to evaluate labral pathology, but other radiologists find it as accurate to perform noncontrast MRI to evaluate shoulder labral pathology (8,9) (Fig. 9.1). Contrast is not needed in the acute evaluation of shoulder instability due to the presence of a hematoma.

SURGICAL PROCEDURE

Anesthesia and Positioning

A majority of the patients receive an interscalene nerve block and general anesthesia. The interscalene block is helpful in limiting intraoperative narcotics and decreases postoperative pain and nausea.

The patient is anesthetized supine on a full-length bean bag and the operating table is configured into the beach chair position. The procedure can be performed in either the lateral decubitus position or the beach chair position and is largely surgeon dependent. The advantage of the lateral decubitus position is that traction on the arm can allow for better visualization and easier placement of anchor in the inferior aspect of the anterior glenoid.

Once the patient is properly positioned, the bean bag is inflated to secure the patient in the upright position. The bean bag must be properly folded to leave the entire medial border of the scapula free. This set up allows excellent control of the head and body during the procedure, and is easy to adapt for people of any body habitus. Once the beanbag is inflated, the patient and the beanbag are brought laterally to the edge of the bed, allowing complete exposure of the shoulder to the medial border of the scapula (Fig. 9.2). The arm is prepped and draped in standard fashion. In cases where an open procedure is performed, we routinely use an Ioban dressing in the axilla in order to decrease the risk of infection. A McConnell arm holder is used for both arthroscopic and open stabilizations. It is extremely useful to provide distal traction during the stabilization procedure.

Exam under Anesthesia

Prior to any incision, it is critical to perform an examination of the shoulder under anesthesia. The examination should be performed on both shoulders to assess asymmetry in the exam compared to the contralateral side. Range of motion is recorded as well. Exam under anesthesia should confirm grade 2 to 3+ anterior instability without any posterior or inferior translation. In some cases of inferior laxity, however, there will be some degree of inferior subluxation, and this should be accounted for in the capsular placation or rotator interval closure.

Portal Placement

There are typically three portals used for anterior stabilization of the shoulder. The primary viewing portal is made posteriorly in line with the glenohumeral joint. This portal is located 2 cm distal and medial to the posterolateral tip of the acromion. There are two anterior portals, and these must be carefully placed in order to facilitate the remainder of the procedure. The first portal is placed with an outside in technique with a spinal needle. It is placed in the rotator interval, just above the subscapularis tendon, laterally enough to facilitate placement of anchors at a 45-degree angle to the glenoid. The final portal is placed in the superior aspect of the rotator interval, just anterior to the biceps tendon. This facilitates suture management and can be utilized for anchor placement if a SLAP repair is necessary. We typically use a 7 to 8 mm clear cannula so that all instrumentation can be managed via either anterior portal.

Diagnostic Arthroscopy

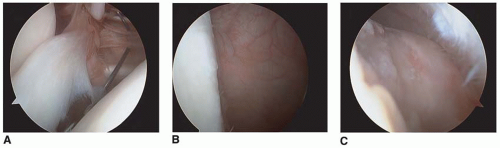

In cases where we suspect that an open procedure is necessary, we routinely perform a diagnostic arthroscopy to evaluate the status of the entire glenohumeral joint. The injury is classified based on the type of lesion that is found on the anteroinferior glenoid. A Bankart lesion is a disruption of the labrum off the glenoid rim, with or without disruption of the glenohumeral ligaments (Fig. 9.3). A Perthes lesion occurs when there is a periosteal avulsion of the labrum together with the glenohumeral ligaments off the glenoid neck. If the labrum scars medially following this injury, it is termed an ALSPA lesion (anterior labrum periosteal sleeve avulsion).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree