Anterior Cervical Discectomy and Fusion with and without Instrumentation

John M. Rhee

Claude Jarrett

Sam W. Wiesel

DEFINITION

Cervical spondylosis refers to degenerative conditions affecting the cervical spine, including disc degeneration, herniation, facet arthrosis, and osteophytic spur formation. Depending on the nature and location of the spondylotic changes, pathologic compression of neural structures in the cervical spine may occur.

This chapter focuses on anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) as a surgical treatment option for patients with cervical radiculopathy. Cervical myelopathy can also be treated with ACDF as long as the spinal cord compression occurs at the disc rather than the retrovertebral level.

All techniques described in this chapter can apply to the decompression of the spinal cord in myelopathic patients as well as the nerve root in radiculopathic patients. However, for the purposes of organization, cervical myelopathy is discussed in the chapter on anterior cervical corpectomy.

ANATOMY

The anterior longitudinal ligament is a wide band of ligaments stretching along the anterior surface of the vertebral bodies. Its dense longitudinal fibers widen as they travel caudally and are intimately associated with the intervertebral discs as well as the vertebral endplates.

The posterior longitudinal ligament (PLL) is a smooth and shiny group of dense ligaments that course along the posterior surface of the vertebral bodies within the spinal canal. The PLL tends to be thicker centrally and thins out laterally as it attaches to the uncinate regions. Bulging or ossification of the PLL (OPLL) can cause spinal cord compression.

The intervertebral disc comprises the outer annulus fibrosus and the central gelatinous nucleus pulposus. Each disc is attached to the subchondral bone of the adjacent vertebral bodies. The outermost rim of the vertebral endplate is not attached to the disc, leaving a ring of exposed bone that may be more prone to forming arthritic spurs.

The uncovertebral joints are critical bony landmarks for anterior cervical decompression (FIG 1). Spurs commonly arise from these articulations and cause impingement of the exiting roots as they enter the foramen.

Depending on the cervical level, the vertebral artery may be as close as 5 mm away from the medial aspect of the uncinate process.

Each cervical spinal nerve is composed of dorsal and ventral roots. The ventral root lies dorsal to the uncovertebral joint, whereas the dorsal root is ventral to the superior articular facet.

It is important to keep in mind when performing uncovertebral osteophyte resection that the nerve root leaves the spinal cord at roughly a 45-degree angle ventrolaterally in the axial plane. Thus, care must be taken to hug the posterior surface of the uncinate to avoid injury to the exiting root.4

Table 1 Neurologic Examination of the Cervical Spine | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

PATHOGENESIS

Neural impingement occurs in two main locations: within the spinal canal, affecting the spinal cord, the nerve root, or both; or within the foramen, where the exiting root can be affected.

Depending on whether the involved structure is the spinal cord or the nerve root, patients can present with symptoms of myelopathy, radiculopathy, or both.

NATURAL HISTORY

The natural history of cervical radiculopathy is generally favorable with most patients having spontaneous resolution or considerable improvement of their symptoms over time.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

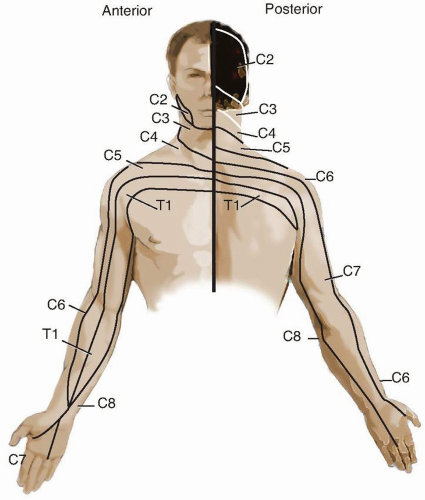

Patients with radiculopathy typically present with radiating pain, paresthesia, or motor weakness (Table 1). However, the pattern of symptoms is not always dermatomal (FIG 2).

On examination, patients with radiculopathy may have motor, sensory, or reflex changes along the affected nerve root distribution. However, the neurologic examination findings may be normal.

Patients may express exacerbation of radicular pain with particular head positions (ie, head positions that narrow the size of the neural foramen such as neck extension with rotation to the affected extremity).

This can be elicited by performing the Spurling test. The Spurling sign is very helpful in differentiating cervical radiculopathy from extraspinal causes, such as cubital or carpal tunnel syndromes, as reproduction of symptoms should occur only with a cervical source of compression.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Plain radiographs, although of limited value in evaluating neural compression, remain a commonly acquired initial study and can be used to evaluate overall alignment, spinal instability, or bony pathology, including spur formation.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the modality of choice for evaluating neural compression.

Computed tomography (CT) myelography provides outstanding resolution of bony and neural anatomy, but it is less appealing as it requires an invasive procedure. It is typically recommended for patients with contraindications to MRI (eg, prosthetic heart valve, pacemaker) or when MRI fails to provide sufficient detail.

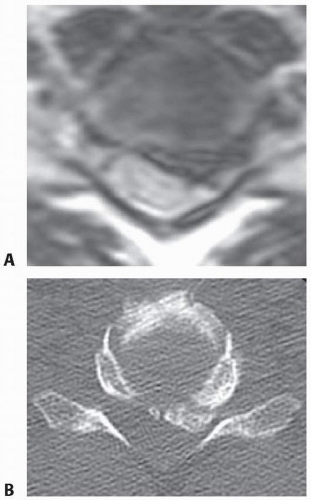

If a high-quality MRI is available but questions remain regarding bony anatomy for the purposes of surgical planning, a noncontrast CT scan provides complementary information (eg, differentiating soft disc versus ossified disc or OPLL) (FIG 3).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Cervical radiculopathy

Cervical myelopathy

Brachial plexus injury

Complex regional pain syndrome or reflex sympathetic dystrophy

Thoracic outlet syndrome

Inflammatory arthropathy

Spinal cord tumor

Angina

Shoulder pathology

Peripheral nerve compression (eg, carpal or cubital tunnel syndrome)

Diabetic neuropathy

Multiple sclerosis

Syringomyelia

Stroke

Guillain-Barré syndrome

Normal pressure hydrocephalus

Spinal cord tumor

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Nonoperative management should be considered as the initial mode of treatment for most patients with radiculopathy.

Nonsurgical treatment typically includes physical therapy, traction, pain medication, cervical collars, and epidural injections. It is not clear if nonoperative modalities alter the natural history, but they can provide pain relief while the natural history runs its course.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Surgical intervention is indicated for radiculopathy in patients with persistent symptoms resistant to nonoperative care, progressive weakness, or instability.

Common surgical approaches to radiculopathy include ACDF versus posterior laminoforaminotomy.11

Preoperative Planning

The surgeon should evaluate imaging studies for anatomic variations, such as medial aberrancy of the vertebral artery.

To perform a safe but complete and adequate neural decompression, high-quality illumination and magnification are essential.

An operating microscope provides illumination and visualization superior to that of loupes and headlights, but either method can be used.

Another advantage of the microscope is that the view obtained by the assistant is the same as that of the operating surgeon.

If the surgeon chooses to use the microscope, given the smaller field of view, it is imperative to continuously adjust the viewing angle such that a line of sight parallel to the disc space is achieved (FIG 4). If this is not done, the surgeon may inadvertently stray away from the disc space, veer into one vertebral body or the other, and not proceed

to the back of the disc space where the decompression needs to occur.

Positioning

The patient is positioned with a bump under the scapula and the occiput on a foam doughnut to prevent pressure necrosis.

The amount of extension tolerated preoperatively without excessive pain or neurologic symptoms is recreated.

Approach

A standard Smith-Robinson approach to the anterior cervical spine is used for most cases from C2 to T2.

TECHNIQUES

▪ Anterior Cervical Discectomy and Fusion with Instrumentation

Initial Discectomy

Once the disc is exposed, it is sharply incised with a no. 15 blade and removed with a combination of curettes and pituitary rongeurs.

The disc and cartilaginous material should be removed until the PLL and both uncinate processes are visualized (TECH FIG 1A).

An important maneuver to facilitate disc space visualization and neural decompression is to remove the anterior portion of the inferior endplate of the superior vertebral body (the anterior lip). Doing so provides a direct line of sight into the posterior disc space, which facilitates later foraminotomy and resection of the PLL, if necessary.

This surface is almost always concave, with the anterior portion overhanging the disc space, thus preventing direct visualization of the posterior disc space.

Removal can be done with either a Kerrison rongeur or a highspeed burr.

Flattening this surface also facilitates optimal graft-endplate contact (TECH FIG 1B).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree