Anterior Cervical Corpectomy and Fusion with Instrumentation

John M. Rhee

Claude Jarrett

DEFINITION

Cervical myelopathy describes a constellation of signs and symptoms resulting from cervical spinal cord compression. Common symptoms include gait instability, clumsiness and loss of manual dexterity, and glove-like (rather than dermatomal) numbness of the hands.

Because the presentation of myelopathy can be subtle, especially in its early manifestation, the diagnosis can be missed or wrongly attributed to “aging.”

Surgical decompression is the mainstay of treatment and can be accomplished anteriorly (ie, corpectomy, discectomy and fusion, or both), posteriorly (ie, laminectomy and fusion or laminoplasty), or through a combined anterior-posterior approach depending on the pattern of spinal cord compression.

Anterior corpectomy and fusion will be discussed in this chapter. Corpectomy is performed when retrovertebral compression of the spinal cord exists. If the compression is purely disc-based, corpectomy is not necessary, and an anterior cervical discectomy and fusion approach can be used instead.

PATHOGENESIS

Spondylotic changes (eg, bone spurs, disc degeneration with annular bulging, disc herniations) are the most common causes of cervical cord compression.

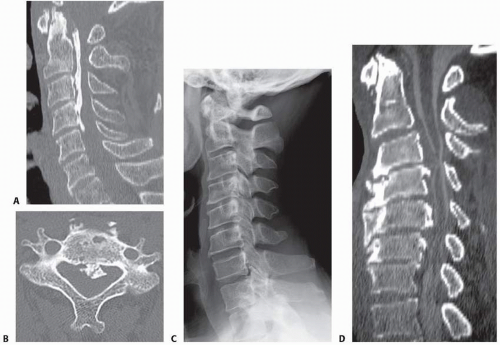

Ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL) is another not uncommon cause of cord compression. It may arise in discrete locations or be continuous (FIG 1A,B).6

Kyphosis, whether primary or occurring after laminectomy, can also cause cord compression and myelopathy.

Cervical myelopathy often arises in the setting of a congenitally narrowed cervical canal (FIG 1C,D). In these patients, the cord may have escaped compression during relative youth but not after the accumulation of a threshold amount of space-occupying spondylotic changes.

Although cervical spondylotic myelopathy tends to be a disorder seen in patients 50 years of age or older, depending on the degree of congenital stenosis and the magnitude of the accumulated spondylotic changes, it can be seen in patients who are much younger.

NATURAL HISTORY

Patients with cervical myelopathy are generally thought to have a poor prognosis without surgical treatment, with a gradual stepwise progression of symptoms.1

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Patients with cervical myelopathy present with a spectrum of upper and lower extremity complaints.

Upper extremity complaints include a generalized feeling of clumsiness of the arms and hands, “dropping things,” inability to manipulate fine objects such as coins or buttons, trouble with handwriting, and diffuse (nondermatomal) numbness.

Lower extremity complaints include gait instability, a sense of imbalance when walking, and “bumping into walls” when walking. Family members may comment that the patient walks as if he or she is intoxicated.

Patients with severe spinal cord compression may also complain of Lhermitte symptoms: electric shock-like sensations that radiate down the spine or into the extremities with certain offending positions of the neck (can occur with either flexion or extension).

Many myelopathic patients deny any loss of motor strength. Similarly, bowel and bladder symptoms, if present, may arise in the later stages of disease. Despite advanced degrees of spondylosis, many myelopathic patients may have no neck pain.

Symptomatic nerve root compression can coexist in patients with myelopathy and presents as a myeloradiculopathy.

Physical examination should include the following:

Scapulohumeral reflex testing, which is positive with hyperactive elevation of the scapula or abduction of humerus upon tapping the spine of the scapula. This finding may be associated with high cervical cord compression from C1 to C3.

Jaw jerk reflex, which is positive with hyperactive jerking of the jaw upon tapping.

Test for the Babinski sign, which is positive if the great toe extends while the remaining toes fan apart upon stroking the lateral sole of the foot and then curving across the metatarsal heads medially

Test for the Hoffman sign, which is positive with spastic flexion of the index finger and thumb upon flicking the distal phalanx of the middle finger

Inverted radial reflex test, which is positive if one observes flexion of fingers rather than a reflex contraction of the brachioradialis upon tapping the brachioradialis tendon. Positive result suggests cord and root compression at the C5-C6 level.

Test for finger escape sign, which is positive if the little finger (also possibly the ring finger) cannot be held in this position without falling into abduction and flexion for more than 30 seconds. This is suggestive of cervical myelopathy.

Tandem gait test, which is positive if the patient demonstrates significant instability. A positive result confirms gait imbalance but in no way specifies the source of the imbalance as being the cervical spinal cord.

It is important to note, however, that patients with cervical myelopathy may not necessarily have “classic” physical findings. One study3 demonstrated that about 20% of patients with myelopathy do not display any obvious physical

findings (eg, hyperreflexia, Hoffman sign). Thus, the absence of physical findings does not necessarily exclude the diagnosis of cervical myelopathy.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

A lateral radiographic view can be helpful in showing the amount of congenital cervical stenosis as well as sagittal alignment.

Lateral views are consistent with congenital stenosis when the ratio of the diameter of the canal to the diameter of the vertebral body is less than 0.8.

Particularly if OPLL is suspected, computed tomography (CT) scans (with or without myelograms, depending on whether a high-quality magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] is available) are helpful in delineating bony versus soft tissue pathology.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Of cervical myelopathy

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

Myopathies

Peripheral neuropathy

Syringomyelia

Multiple sclerosis

Diabetic neuropathy

Brachial plexopathy

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Surgery is generally the treatment of choice for symptomatic cervical myelopathy.

Nonoperative treatment of cervical myelopathy is typically reserved for patients who cannot tolerate surgery.4

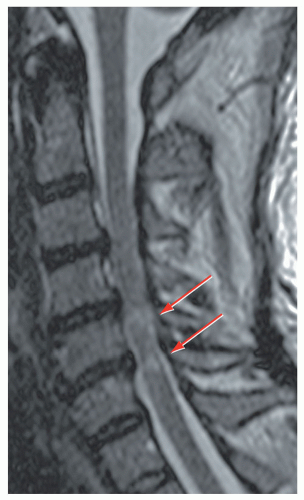

Controversy exists regarding the management of patients with asymptomatic spinal cord compression. In those with severe asymptomatic compression, consideration should be given to prophylactic surgery, particularly if cord signal changes are present, to prevent spinal cord injury with trauma (eg, central cord syndrome) (FIG 2).

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

The most common surgical options include anterior decompression and fusion (discectomy vs. corpectomy, depending on the absence or presence of retrovertebral cord compression, respectively), laminoplasty, and laminectomy with fusion.

In general, anterior surgery is preferred when cord compression arises from three or fewer disc segments, as the incidence of fusion and graft complications increases substantially with greater number of segments fused. The presence of kyphosis or significant spondylotic neck pain also favors an anterior approach.

Conversely, posterior approaches such as laminoplasty are favored when myelopathy arises from three or more motion segments and the cervical alignment is neutral or lordotic, particularly if the patient has minimal to no neck pain.

For posterior surgery to adequately decompress the cord, however, enough lordosis must be present to allow cord to drift back after removal of the posterior tethers (lamina, flavum).

Combined anterior and posterior surgery should be considered in cases of significant kyphosis, whether primary or postlaminectomy.

Multilevel corpectomy as a stand-alone operation is generally not recommended due to a relatively high propensity for frank construct failure or sagging into kyphosis. Plating does not reliably prevent such failures. Failures of stand-alone multilevel corpectomies are even more likely in patients with significant postlaminectomy kyphosis. In cases where multilevel corpectomy is needed, supplemental posterior fixation should be considered.

Preoperative Planning

Preoperative CT and MRI scans should be scrutinized to analyze the course of the vertebral arteries and the width of the spinal canal requiring decompression.

CT scans may provide additional information to MRI scans when it is unclear whether the compressive lesions are bony (OPLL, osteophytes) or soft disc material.

Positioning

For anterior cervical corpectomy and fusion, patients are positioned as described in Chapter 1.

However, greater caution is necessary in positioning the myelopathic versus radiculopathic patient. In particular, one must ensure that the patient is not excessively extended beyond the tolerance of the compressed cord. The amount of extension tolerated preoperatively should be assessed and not exceeded intraoperatively.

Gardner-Wells tongs traction is optional when performing corpectomy, especially if a multilevel corpectomy is needed. In general, traction can be generated intraoperatively for one or even two-level corpectomies through Caspar pins without need for external tong traction.

Significant distraction on the cervical spine should be avoided until after the cord has been decompressed to avoid stretching the cord over compressive pathology.

Approach

The approach is similar to that for anterior cervical discectomy and fusion but generally needs to be more extensile to access multiple levels. (Please see Chap. 1 for further details.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree