Chapter 2 Anatomical Landmarks for Therapeutic Massage

Knowledge of anatomy, especially that which is on the surface or creates superficial landmarks, is essential for performing therapeutic massage. It is important to know in which direction muscles run, where they attach to bone or cartilage, their relationships with blood vessels and nerves, and whether these structures are deep or superficial. Bony structures visible or palpable from the surface are key elements to identifying these soft tissue structures. Arteries and nerves are delicate and easily damaged, so it is vital to be aware of their position when performing soft tissue massage. Also, deep friction massage can be done to specific tendons and ligaments, so knowledge of their position is important.

HEAD AND NECK

Head

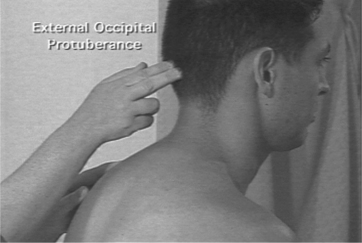

Bony prominences of the head and neck provide a frame of reference for location of important structures. The mastoid process is a prominent bony process of the temporal bone and is found posterior to the ear. It is important as the insertion for the sternocleidomastoid muscle. Another significant bony prominence is the external occipital protuberance (or inion), found on the occipital bone (Figure 2-1). Extending caudally from the external occipital protuberance and the posterior border of the foramen magnum, there is a superficial ligament of significance, the ligamentum nuche (or nuchal ligament). This structure extends from the external occipital protuberance along the spinous processes of the cervical vertebrae. This ligament helps to provide a site for muscle attachments.

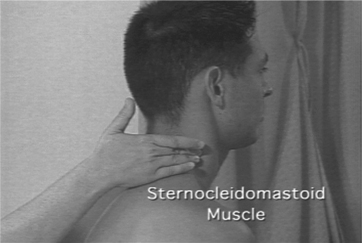

Laterally, another structure of significance in the head is the transverse process (TP) of the second cervical vertebra (C2). This landmark is identified by first locating the angle of the mandible. The TP of C2 is found between the angle of the mandible and the mastoid process. An important muscle landmark in the neck, just posterior to the TP of C2, is the sternocleidomastoid muscle (Figure 2-2), best viewed with the neck extended against resistance. This muscle originates from the manubrium of the sternum and the clavicle and inserts onto the mastoid process of the temporal bone and the superior nuchal line of the occipital bone.

Neck

Deep to the trapezius muscle are the splenius muscles (cervicis and capitis). These muscles reflect the meaning of the word splenion, meaning bandage, and extend from the spinous processes of cervical and thoracic vertebrae to the transverse processes of the cervical vertebrae and the skull. In the posterior neck, this muscle is found in a space bounded by the trapezius muscle posteriorly, the levator scapulae inferiorly, and the sternocleidomastoid muscle anteriorly.

UPPER LIMB

Shoulder

The scapula is a prominent flat bone on the dorsal aspect of the shoulder, between ribs 2 and 7. It articulates with the clavicle anteriorly and the humerus laterally. The medial border of the scapula can be pulled away from the back, along with the inferior border (at T8). The anterior border of the scapula is palpated best from the axilla. The most prominent posterior portion of the scapula is the spine (at T3), which provides a surface landmark to divide the posterior aspect of the scapula into supraspinous and infraspinous portions. The lateral end of the spine widens to form the acromion (Figure 2-3). At the angle of the acromion, where it changes direction, the deltoid muscle originates to form a cap over the shoulder. An additional important bony prominence on the scapula is the coracoid process. This process is medial to the head of the humerus as well as the acromion and is inferior to the clavicle. Several important muscles attach here (pectoralis minor, coracobrachialis, short head of the biceps).

The deltoid muscle caps the shoulder. It has anterior, intermediate, and posterior portions. With the upper extremity in the anatomical position, the anterior portion is visible when the patient flexes the shoulder against resistance. The intermediate portion is visible when the patient abducts the arm against resistance. With the shoulder in extension, the posterior portion of the deltoid is visible at the shoulder.

Arm

The arm, or brachium, is separated into anterior and posterior compartments. The most superficial, visible muscle of the anterior compartment is the biceps brachii muscle. It has, as the name implies, two heads of origin. The short head takes its origin from the coracoid process of the scapula, whereas the long head originates from the supraglenoid tubercle within the shoulder joint. Both heads are observed with the arm in the anatomical position. With the patient’s shoulder flexed and forearm supinated, the therapist can easily see the belly of the long head along its entire length until it disappears under the anterior portion of the deltoid. The insertion of the biceps, the biceps tendon, can be palpated as it attaches to the radius. The biceps muscle also ends as an aponeurosis (Figure 2-4), or broadened flat tendon, inserting into the ulna. This bicipital aponeurosis forms the roof of the cubital fossa and protects the brachial artery and the median nerve.

Forearm

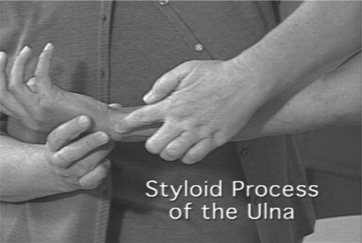

The ulna is the medial bone of the forearm and serves to stabilize this area. The posterior border of the ulna can be palpated, extending from the olecranon process to the wrist. The distal end of the ulna is the styloid process (Figure 2-5). This superficial bony eminence can be seen and palpated easily with the wrist in both extension and flexion.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree