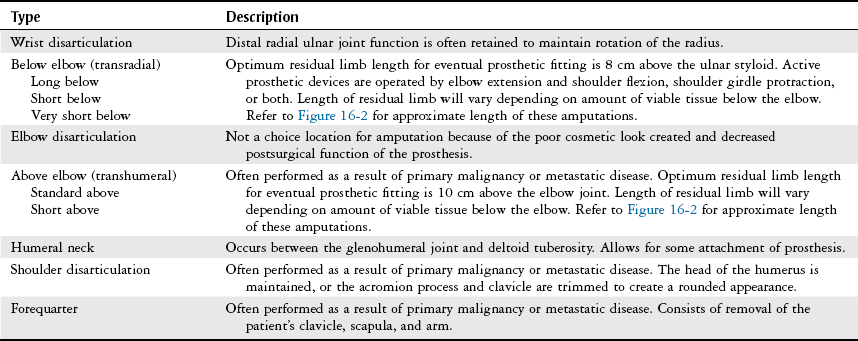

Chapter 16 The objectives of this chapter are the following: 1 Provide an overview of the causes and types of lower-extremity amputation 2 Provide an overview of the causes and types of upper-extremity amputation 3 Describe physical therapy management, pertinent to the acute care setting, for patients with either upper or lower-extremity amputation 4 Provide an overview of applicable standardized outcome measures for this patient population • Impaired Motor Function, Muscle Performance, Range of Motion, Gait, Locomotion, and Balance Associated with Amputation: 4J • Impaired Integumentary Integrity Associated with Skin Involvement Extending into Fascia, Muscle, or Bone and Scar Formation: 7E Please refer to Appendix A for a complete list of the preferred practice patterns, as individual patient conditions are highly variable and other practice patterns may be applicable. Vascular disease and trauma are the primary causes of LEA. In the United States there are approximately 1.6 million persons living with the loss of a limb. Within this population, 38% had an amputation as a result of dysvascular disease along with a concurrent diagnosis of diabetes mellitus (refer to Chapter 10 for more information about diabetes). The number of people living with the loss of a limb is projected to increase to 3.6 million by the year 2050 if the current health status of individuals goes unchanged.1 Traumatic injury from motorcycle accidents and vehicular collisions with pedestrians accounted for approximately 59% of LEA in the years between 2000 and 2004.2 The various locations of LE amputation are shown in Figure 16-1 and are described in Table 16-1. TABLE 16-1 Types of Lower-Extremity Amputations* *Unless otherwise stated, the etiology of these amputations is from peripheral vascular disease. Data from Thompson A, Skinner A, Piercy J, editors: Tidy’s physiotherapy, ed 12, Oxford, UK, 1992, Butterworth-Heinemann, p 260; Engstrom B, Van de Ven C, editors: Therapy for amputees, ed 3, Edinburgh, Scotland, 1999, Churchill Livingstone, pp 149-150, 187-188, 208; May B, editor: Amputations and prosthetics: a case study approach, Philadelphia, 1996, FA Davis, pp 62-63; Sanders G, editor: Lower limb amputations: a guide to rehabilitation, Philadelphia, 1986, FA Davis, pp 101-102; Lusardi M, Nielsen C, editors: Orthotics and prosthetics in rehabilitation, Boston, 2000, Butterworth-Heinemann, pp 370-373; Edelstein JE: Prosthetic assessment and management. In O’Sullivan SB, Schmitz TJ, editors: Physical rehabilitation: assessment and treatment, ed 4, Philadelphia, 2001, FA Davis, pp 645-673. UEA is most often the result of trauma, such as automobile collisions, industrial accidents, or penetrating trauma.2–4 Disease and congenital limb deficiency are also major causes of UEA.5 Despite peripheral vascular disease being a major cause of LE amputation, it often does not create the need for UEA.3 The various locations of UEA are shown in Figure 16-2 and are described in Table 16-2. TABLE 16-2 Types of Upper-Extremity Amputations* *Unless otherwise stated, the etiology of these amputations is from trauma. Data from Engstrom B, Van de Ven C, editors: Therapy for amputees, ed 3, Edinburgh, Scotland, 1999, Churchill Livingstone, pp 243-257; Lusardi M, Nielsen C, editors: Orthotics and prosthetics in rehabilitation, Boston, 2000, Butterworth-Heinemann, p 573; Banerjee SN, editor: Rehabilitation management of amputees, Baltimore, 1982, Williams & Wilkins, pp 30-33; Ham R, Cotton L, editors: Limb amputation: from aetiology to rehabilitation, London, 1991, Chapman & Hall, pp 136-143; Theisen L: Management of upper extremity amputations. In Burke SL, Higgins JP, McClinton MA, et al, editors: Hand and upper extremity rehabilitation: a practical guide, ed 3, St Louis, 2006, Churchill Livingstone, p 716.

Amputation

Preferred Practice Patterns

Lower-Extremity Amputation

Type

Description

Ray

Single or multiple rays can be amputated depending on the patient’s diagnosis. If the first ray is amputated, balance is often affected, as weight is transferred to the lateral border of the foot, which may also cause ulceration and skin breakdown. Postoperative weight-bearing status will range from non–weight-bearing to partial weight-bearing status according to the physician’s orders.

Transmetatarsal

The metatarsal bones are transected with this procedure as compared to other types of partial foot amputations, which may disarticulate the metatarsals from the cuboid and cuneiform bones. Balance is maintained with a transmetatarsal amputation, because the residual limb is symmetric in shape and major muscles remain intact. An adaptive shoe with a rocker bottom is used to help facilitate push-off in gait.

Syme’s amputation (ankle disarticulation)

Often performed with traumatic and infectious cases, this type of amputation is preferred to more distal, partial foot amputations (ray and transmetatarsal) because of the ease of prosthetic management at this level.

Patients may ambulate with or without a prosthesis.

Below the knee (transtibial)

Ideal site for amputation for patients with a variety of diagnoses. Increased success rate with prosthetic use. In cases with vascular compromise, the residual limb may be slow to heal. Residual limb length ranges from 12.5 cm to 17.5 cm from the knee joint.

Through-the-knee (disarticulation)

Often performed on elderly and young patients. Maximum prosthetic control can be achieved with this procedure because of the ability to fully bear weight on the residual limb. Also, a long muscular lever arm and intact hip musculature contribute to great prosthetic mobility. The intact femoral condyles, however, leave a cosmetically poor residual limb.

Above the knee (transfemoral)

Traditional transfemoral amputation preserves 50% to 66% of femoral length. Prosthetic ambulation with an artificial knee joint requires increased metabolic demand.

Hip disarticulation (femoral head from acetabulum)

Often performed in cases of trauma or malignancy. The pelvis remains intact; however, patients may experience slow wound healing and may require secondary grafting to fully close the amputation site.

Hemipelvectomy (half of the pelvis is removed along with the entire lower limb)

Also indicated in cases of malignancy. A muscle flap covers the internal organs.

Upper-Extremity Amputation

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree