Allergic rhinitis alone affects over 60 million Americans (2). It is the fifth most common chronic disease and the most prevalent in patients under 18 years of age, affecting up to 40% of children (2,16).

Urticaria and angioedema affect 20%-30% of the population during their lifetime (9).

Approximately 20,000-50,000 patients with anaphylaxis present for medical care in the United States each year. Annual mortality figures are difficult to quantify, but available estimates indicate anaphylaxis causes up to 1,000 deaths each year (15).

Allergic rhinitis occurs when an individual develops immunoglobulin (Ig) E sensitization to aeroallergens. Inhalation of the aeroallergens leads to mast cell activation and release of histamine and other chemical mediators of inflammation.

Common symptoms include rhinorrhea, postnasal drip, congestion, sneezing, cough, and pruritus of the nose and soft palate. Patients may complain of generalized irritability and fatigue. Eye pruritus, injection, irritation, and watery discharge may indicate coexisting allergic conjunctivitis.

Symptoms recur on exposure to any aeroallergen to which a patient is sensitized.

Spring and early summer exacerbations occur with tree and grass pollination. Late summer and fall symptoms are usually because of weeds and mold. Indoor flares suggest sensitivity to cockroach, dust mites, pet dander, or molds. Perennial symptoms may be sensitive to a combination of these allergens or indicate nonallergic rhinitis.

The etiology of nonallergic rhinitis is unknown.

The prominent complaint is nasal congestion. Nasal, eye, and soft palate pruritus are usually absent. Symptoms are often perennial and triggered by strong odors or smoke. Seasonal air temperature, humidity, and barometric pressure changes may lead to exacerbations, making it difficult to distinguish from allergic rhinitis.

The history should focus on isolating an allergen exposure. A personal or family history of asthma, allergies, and eczema leads to a higher suspicion for allergic rhinitis.

Physical examination will not distinguish allergic and nonallergic rhinitis.

The nasal mucosa in allergic rhinitis is classically pale or bluish, but can be red or edematous or appear normal. Postnasal drip of any etiology causes posterior pharyngeal cobblestoning. “Allergic shiners” from infraorbital venous congestion are also nonspecific.

Findings suggestive of allergic rhinitis include an accentuated transverse nasal crease (seen in children who repeatedly rub their nose because of pruritus), atopic stigmata, such as eczema, and wheezing on auscultation.

Allergen avoidance is essential in managing allergic rhinitis.

Avoidance of animal dander is always best. Exclusion of the pet from the bedroom and high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filter use may provide some benefit.

For dust mite allergy, use occlusive covers on the pillows, mattress, and box springs. Frequent washing of bed linens and blankets in hot water is helpful. Dehumidifiers and removing carpet may help. HEPA filters are ineffective because dust mite products are not airborne for an extended period of time.

Mold allergen can be difficult to control, but dehumidifiers and scrupulous cleaning can be beneficial.

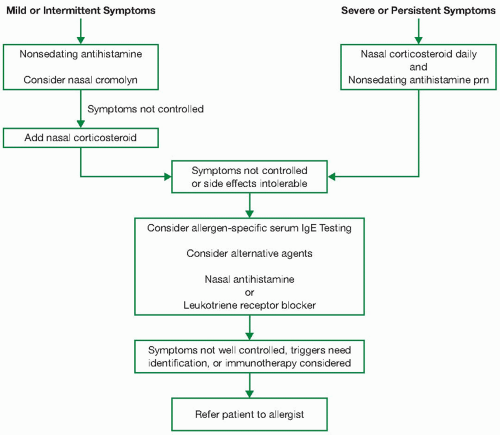

Medical therapy is initiated in a stepwise fashion (Fig. 39.1). Available medications include nasal corticosteroids, antihistamines, decongestants, cromolyn, leukotriene receptor blockers, and nasal ipratropium bromide.

Nasal corticosteroids are the most effective therapy for persistent or severe symptoms (3). Several days of treatment are

usually necessary for maximal effectiveness. They can be used periodically for an athlete’s allergy season, but once initiated, the steroid needs regular administration for optimal efficacy (Table 39.1). Side effects are low and include irritation, burning, sneezing, and bloody nasal discharge.

Figure 39.1: Suggested therapeutic strategy for allergic rhinitis in athletes. IgE, immunoglobulin E; prn, as needed.

Table 39.1 Nasal Corticosteroids

Nasal Corticosteroid

Dose: Sprays per Nostril

Flonase, Veramyst (fluticasone)

Age ≥ 12: 2 daily

Age 4-11: Same but start at 1 daily

Nasonex (mometasone furoate)

Age ≥ 12: 2 daily

Age 2-11: 1 daily

Rhinocort Aqua (budesonide)

Age ≥ 12: 1-4 daily

Age 6-11: 1-2 daily

Omnaris (ciclesonide)

Age ≥ 6: 2 daily

Nasarel (flunisolide)

Age ≥ 15: 2 bid to tid

Age 6-14: 1 tid or 2 bid

Nasacort AQ (triamcinolone)

Age ≥ 12: 2 daily

Age 6-11: 1-2 daily

Beconase and Vancenase AQ (beclomethasone)

Age ≥ 12: 1-2 bid

Age 6-11: 1 bid

bid, twice a day; tid, three times a day.

Chronic nasal steroids, when used properly, are not associated with significant adrenal suppression, nasal or pharyngeal candidiasis, cataracts, or glaucoma (4,5,12). Studies using mometasone furoate and fluticasone in children showed no difference in growth compared to placebo (1,17,19).

Oral antihistamines relieve sneezing, itching, and rhinorrhea in allergic rhinitis. Their efficacy is roughly equivalent to nasal cromolyn but less than nasal steroids. They provide little relief of nasal obstruction and are generally ineffective in the treatment of nonallergic rhinitis. First-generation antihistamines can cause significant sedation, decreased alertness, and performance impairment, making them undesirable for most competitive athletes. These effects can exist without an individual’s awareness and can be present even with nighttime-only dosing. Second-generation antihistamines are at least as effective as first-generation antihistamines and possess much lower rates of sedation (Table 39.2). Antihistamines can decrease heat dissipation by their anticholinergic effects on sweat glands and should be used with caution in athletes.

Nasal antihistamines can be beneficial in both allergic and nonallergic rhinitis. Side effects include drowsiness and an unpleasant aftertaste. While nasal steroids provide greater relief of nasal symptoms, nasal antihistamines can be

considered as an alternative when the response to an oral antihistamine and a nasal steroid is inadequate (24).

Table 39.2 Second-Generation Oral Antihistamines

Second-Generation Oral Antihistamine

Dose

Sedation

Fexofenadine (Allegra)

Age ≥ 12: 180 mg daily or 60 mg bid

Age 2-11: 30 mg bid

No different than placebo

Cetirizine (Zyrtec)

Age ≥ 6: 5-10 mg daily

Age 2-5: 2.5-5 mg daily (syrup)

Slightly higher than placebo but less than first generation

Levocetirizine (Xyzal)

Age ≥ 12: 5 mg daily

Age 6-11: 2.5 mg daily

Age 2-5: 1.25 mg daily (syrup)

Slightly higher than placebo but less than first generation

Loratadine (Claritin)

Age ≥ 6: 10 mg daily

Age 2-5: 5 mg daily

No different than placebo at 10 mg; sedating at higher doses

Desloratadine (Clarinex)

Age ≥ 12: 5 mg daily

Age 6-11: 2.5 mg daily

Age 2-5: 1.25 mg daily

No different than placebo*

bid, twice a day.

* Seven percent of population may have sedation because of decreased metabolism of the drug.

Oral decongestants relieve congestion in allergic and nonallergic rhinitis. In allergic rhinitis, they are most effective when combined with an oral antihistamine (21). Side effects include insomnia, irritability, tachycardia, and palpations. Because they decrease heat dissipation via peripheral vasoconstriction, they should be avoided during training or competition in the heat. Athletes must be aware of the rules of their particular sport. Governing bodies for competitive sports have individual guidelines that may ban certain decongestants (see later section, Athlete-Specific Medication Issues).

Topical nasal decongestants are for short-term control of severe congestion. Their use should not exceed 3 days. If used for more than 5-7 days, they can cause severe rebound congestion and rhinorrhea.

Cromolyn, a topical mast cell stabilizer, provides modest improvement in the sneezing, itching, and rhinorrhea associated with allergic rhinitis and has a low potential for toxicity. It is useful when given prior to allergen exposure but often requires dosing up to 4-6 times daily to be effective.

Leukotriene receptor antagonists (LRAs) provide mild improvement in allergic rhinitis with efficacy similar to second-generation antihistamines (14). Their side effect profile is no different than placebo. They should be considered when nasal steroids and/or antihistamines fail or have intolerable side effects. Patients with concomitant asthma may also benefit from LRA therapy.

Ipratropium bromide 0.03% nasal spray is effective for treating rhinorrhea, particularly vasomotor-induced rhinorrhea triggered by cold air or exercise. It has no effect on pruritus or congestion. Side effects include occasional epistaxis and nasal dryness but no systemic anticholinergic or rebound effects. It is effective when dosed 30 minutes prior to exercise or exposure.

When treatments fail, consider medication inadequacy and noncompliance, as well as the possibility of other diagnoses, such as anatomic or physical obstruction and/or chronic sinusitis.

Because restrictions on over-the-counter and prescription medications can change, an athlete should discuss a medication’s status with the governing body for their particular sport or level of competition prior to its use. This would include the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) and the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA).

The NCAA has no restrictions on any allergy-related products with the exception that any products containing ephedrine are banned.

The WADA standards are more stringent. Ephedrine and pseudoephedrine are both banned. However, the urinary concentration of pseudoephedrine associated with normal therapeutic use typically falls below the WADA limit of 150 µg · mL−1. Oral glucocorticoids are also banned. Injected epinephrine (EpiPen) for emergency use requires a therapeutic use exemption (TUE). Antihistamines, cromolyn, and leukotriene receptor blockers, as well as topical and nasal steroids, are not banned and do not require a TUE. The WADA releases a new list of banned substances each year and requires review by participants and medical staff to ensure compliance (23).

In patients with a history suggestive of allergic rhinitis, indications for referral for skin testing include targeting allergens for avoidance, as well as institution of immunotherapy when medical therapy is failing. Allergy consultation is recommended prior to drastic environmental interventions,

such as pet elimination, taking up carpets, or purchasing new mattresses, bedding, dust mite covers, and the like.

Antihistamines should be stopped 1 week prior to testing, so as not to blunt the cutaneous response to skin testing.

Allergy testing is contraindicated in the setting of severe lung disease or poorly controlled asthma with a forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) of less than 70%.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree