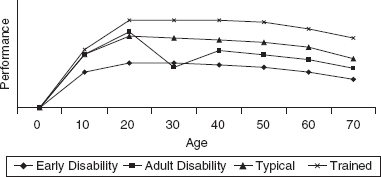

21 AGING WITH PEDIATRIC ONSET DISABILITY AND DISEASES Margaret A. Turk, Jan Willem Gorter, and Lynne Romeiser Logan Aging is a fact of life, and although many may not be well prepared for typical aging changes, current wisdom suggests this is not an unexpected event. However, aging with a disability can be an overwhelming and alarming situation, especially for those experiencing changes in function or health at an earlier-than-expected time. These changes can also mean the difference between living alone with minimal to no support and requiring a more restrictive living environment, including a move to an institutional setting, at a young age. It is essential to understand the developmental course of disability over the life span, and to provide comprehensive health care that focuses on primary and secondary prevention, as well as medical treatment and psychosocial care for aging people with pediatric-onset disability and conditions. For years, children with disability and their families have been told that health and functional status, mobility, and musculoskeletal problems essentially stabilize by early adulthood. Recent longitudinal studies have noted that trajectories of functional status differ by gross motor function and intellectual ability in children with cerebral palsy (CP) (1–4). And as more people with lifelong mobility and other impairments live through their adult years, it is apparent that mobility, functional status, and musculoskeletal changes commonly continue into adulthood (5–7). In fact, questions and concerns about mobility, function change, and pain are common among the majority of adults with mobility impairments caused by any etiology (8). Despite the personal accounts and experiences of those with disability, their families, and many clinicians, there are no longitudinal studies on disability crossing the life span and few surveys or statistics that can document these aging changes and risk factors for them. Present statistics estimate that the number of Americans of all ages with disability (broadly defined by impairment, functional limitation, or participation restriction) exceeds 40 million, and may be closer to 50 million (8). However, these are estimates using multiple national surveys, cross-analyzed in an attempt to cover all ages and living situations. Many of these surveys exclude those living in institutions or assisted living programs (where a number of adults with congenital or childhood-onset conditions may live), and many exclude young children or adults younger than retirement age. There are no U.S. national surveillance programs that monitor the trajectory of aging with a disability by specific disability condition, by severity, or by age of onset over a lifetime, although there are international registries that are beginning to provide information about adolescents and young adults. Data do identify that more infants, children, and young adults are surviving with conditions that were at one time fatal such as CP (9–11), spina bifida (SB) (12,13), muscular dystrophy (14), and childhood-onset epilepsy (15). Moreover children and young adults are completing and surviving long-term risk treatments (eg, chemotherapy, radiation, surgery). In the United States, approximately 500,000 children and youth with special health care needs turn 18 years annually (16). Thus, there is an increasing population of adults with disability, with accompanying risks for long-term complications and additional conditions. There have been changes in a few health conditions in childhood that contribute to adults with disability statistics. The incidence of SB dropped from 24.9 to 18.9 per 1,000 live births with the use of folic acid supplements in women of childbearing age (17). Lead exposure, a risk factor for neurodevelopmental problems, has dropped significantly, with reported lead levels now below 2% (18). Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) have both increased in prevalence, likely related to service availability and classification, better definition of diagnosis and early recognition, and increased prevalence of prenatal risk factors (19). Advances in medical care and public health practices will continue to change the face of the types of disability seen in adults with early-onset conditions in the future. Table 21.1 identifies the leading chronic health conditions as causes of activity limitations, using the 2008–09 National Health Interview Survey (20). As is noted, the listed chronic conditions do not necessarily list disability types typically identified in medical rehabilitation systems as identified by diagnosis, International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes, or diagnostic-related groups, but rather by more generalized conditions. The pediatric chronic conditions listed are largely cognitive and mental-health-based. The only estimate of adults with early-onset disabilities is by Verbrugge and Yang (21) using data from the 1994 National Health Interview Survey Disability Supplement, Phase 1, suggesting that 7% to 9% of adults reporting a disability had onset before the age of 20 years. The surveillance data available imply that the prevalence of disability diagnoses typical of rehabilitation program settings is small compared to other conditions, and usually not the primary focus of public health, surveillance, and policy programs. CHRONIC CONDITION* NUMBER OF CASES PER 100,000 CHILDREN (SE) Speech problems 1,815 (87.5) Learning disability 1,775 (86.8) Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder 1,715 (74.7) Other mental, emotional, or behavioral problems 1,452 (75.9) Other developmental problems 779 (57.1) Asthma/breathing problem 632 (48.4) Other impairment/problems 431 (36.5) Birth defect 423 (35.7) Bone/joint/muscle problem 260 (31.0) Hearing problem 256 (29.9) Vision problem 244 (27.1) Intellectual disability 207 (25.9) Epilepsy/seizures 173 (24.6) Injuries 76 (16.4) * Categories are not mutually exclusive—more than one condition could be reported as contributing to the child’s activity limitation. Most of the health and function information regarding aging in congenital and childhood-onset disability that is known is derived from existing databases developed for service or financial reasons, case studies and series, limited survey information, cross-sectional studies, opinion pieces, and the like. Much of the conventional wisdom in this area has been communicated through the network of persons with disabilities and, more recently, through books and texts. There is minimal systematic information regarding the impact of commonly practiced interventions over a lifetime, including environmental approaches to barriers. Health care providers receive minimal education regarding disability and/or aging with a disability during undergraduate and graduate education (22,23). Therefore, health care providers and consumers have limited knowledge from which to base decisions regarding adult health issues and anticipated changes in function. However, individuals with disability do require ongoing medical, dental, and specialized services to maintain health, decrease morbidity, and improve quality of life (QOL) (24). This chapter will provide a conceptual framework regarding aging as it relates to congenital and childhood-onset disability, review general issues of health and function across early-onset disability, discuss lifelong functional status and health issues of adults with specific early-onset disability, and consider the issues surrounding health care access and transitioning from pediatric to adult care services. Since the last edition, there has been a significant increase in research about adults with CP, SB, and intellectual disability (ID). Additionally, there has been an increasing population of adult survivors of childhood-onset cancers, especially brain tumors, who are seeking care from physiatrists. These advances have been included along with research about participation and QOL as it relates to health and adults with pediatric-onset disability. Improved medical care, increased life expectancy, and better services for lifelong care and support in society have provoked an interest and need for long-term future planning. This includes transitions in care from typical nurturing pediatric care systems to more traditional adult self-directed services. Although the notion of transition of youth with chronic conditions and disabilities is not new, the complexity of transitions, the possible negative outcomes in health, and the need for understanding aging with disability are now being recognized (25). Retrospective reviews and anecdotal experiences also question some long-held beliefs of “use it or lose it” to one of “conserve it to preserve it (26).” Choice of health care providers for adults with early-onset disability and special health care needs is, unfortunately, often limited by insurance and expertise. Clinicians with an understanding of the natural history of disabling conditions can be helpful in monitoring, keeping vigilance for, and prevention of some general health conditions and aging or secondary conditions seen in disability. This public health model of prevention also includes tertiary prevention with the use of environmental modifications and technologies and removal of barriers to participation. There are general aging, associated conditions, secondary conditions, and health concepts that are helpful in understanding a life-span perspective. Aging is a developmental process. It begins at birth and continues to death. Typically, however, children and adolescents are said to develop, whereas adults, especially adults over 50 or 60, are said to age. During the early stages of aging (infancy, childhood, adolescence), attainment of skills and capabilities is on the rise; in the middle stages (adulthood), maintaining and retaining function is the focus. Over a normal life span, natural physiologic declines are not truly preventable, although they may be accelerated or slowed by a variety of individual genetic factors, personal behaviors (eg, diet and exercise), health care practices, and environmental conditions. Aging changes in motor performance seem to be accelerated in some adults with early-onset disability, with earlier-than-typical manifestation of slowed or decreased motor performance and pain complaints. Persons with disability follow a course of aging, although likely with a slower and lower attainment of skills and a smaller capacity to adjust to acute or intercurrent health or medical and surgical intercedents (Figure 21.1). This is a conceptualization, so it is important to recognize that not all disability types respond in the same way to aging. Nevertheless, the emphasis here is on aging with disability, not aging into disability (27). There is also a need to appreciate the different time dimensions at play (8). These include the age of onset of disability in relation to developmental maturity (congenital onset versus acquired onset), the number of years spent with a disability (hemiparesis onset noted at birth versus onset at age 17 years), cumulative effects of medications or treatments (long-term steroid use), and era of disability onset (CP onset in 1950s versus 1990s versus 21st century), including different treatments, opportunities, and attitudes. Anticipated aging changes and treatment strategies will be modified by these temporal concepts. FIGURE 21.1 Conceptual model of aging and performance. Performance is a conceptual quotient of multiple skills. The trained person will achieve a higher level of performance than typical and, assuming ongoing exercise, will have a slower decline with age. With the onset of disability in adult years, there is more loss of skill than improvement, but often not achieving the previous typical level. Those with early-onset disabilities do not achieve full “performance” and are slower to achieve the maximum level. Secondary conditions are defined as “any additional physical or mental health condition that occurs as a result of having a primary disabling condition (8,28).” The initial concept and intended use (29) distinguishes secondary health conditions from the social and economic consequences that may follow a primary disabling condition (societal limitations and barriers—for example, poverty with disability, social isolation, limited transportation). There are key common features of secondary conditions (28): • Causal relationship to the primary disability—the primary disability is a risk factor for the secondary condition • Preventable or modifiable conditions • Variability in expression and timing of manifestation • Capability to increase the severity of the primary condition • Potential to become the primary health concern Many secondary conditions are linked across several primary disabling conditions through common physiologic processes or functional characteristics. As an example, disabilities with sensation changes and immobility are risk factors for pressure ulcers, such as spinal cord injury (SCI), SB, multiple sclerosis, and severe brain injury. Three common secondary conditions noted through cross-disability studies are fatigue, chronic pain, and depression (30,31). The health of aging people with childhood-onset conditions can be seen as a dynamic balance between opportunities and limitations, shifting through life (32). Health perception is an individual determination, and is affected by personal expectations, experiences, sense of vulnerability, support, and locale. How people with disability self-rate their health has been questioned (33). This self-concept may also direct consideration of engagement in typical health and wellness activities. Often, the health of persons with disability is perceived as poor by clinicians and providers when individuals report a positive perception of their own health. This health provider concept may limit the offer of screening or health promotion opportunities. Perception of health in adults with disability may be related to time of onset; it is reported that adults with early-onset disability may identify better health than those with adult-onset disability (34,35). Research further suggests that adults with disability likely have a different construct of and self-rating process for health (36). Therefore, there has been growing interest in concepts associated with QOL. QOL is a multidimensional construct reflecting subjective perceptions of the individual’s position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which he or she lives and in relation to the individual’s goals, expectations, and concerns (37). QOL refers to the notion of holistic well-being, whereas health-related quality of life (HRQOL) specifically focuses on health-related aspects of well-being (37). HRQOL includes elements about physical and mental functioning, as well as the person’s appraisal of their effect on daily life and social functioning. For individuals with disability, HRQOL may be restricted. In general, persons with nonprogressive disabilities should be considered healthy, with a shift of the health care model from an illness and disability paradigm to one of wellness and prevention or early identification of secondary conditions, aging issues, and/or comorbidities. GENERAL KNOWLEDGE REGARDING HEALTH AND PERFORMANCE A body of literature has accumulated regarding health, aging, and secondary conditions for adults with disabilities and for some specific disabilities of early onset. Most research has focused on disabilities and impairments that have relative higher prevalence rates (eg, CP, ASD, speech–language disorders); are easy to associate with a disability group (eg, SB, Down syndrome [DS]); benefit from organized, dedicated service programs (eg, muscle disorders); and therefore have attracted research funding to generate a significant body of knowledge about the condition. The literature includes a combination of scientifically observed and anecdotal information as the database, often involving a “convenience” sample and a cross-sectional approach. Conclusions are drawn from patient reports, clinical observations, and ICD codes. More recently, standardized surveys or severity measures are used, and these provide a glimpse into individual characteristics or outcomes. Most studies identify health issues or concerns, with few challenging prevention or intervention strategies. Each factor in the interaction of disability and aging or secondary conditions has the capability to become a “negative feedback loop” (38) that may lead to further disability or a new health condition. There are studies using cross-disability groups that may have a higher representation of certain disability groups or may be small sample sizes, and consequently generalization to other disability groups should be considered with caution. In a similar manner, prevalence rates for some aging, secondary, and health conditions in disability-specific studies cannot be applied to all disability groups. Pain is a common health condition for adults with disability, as noted earlier, and may be seen earlier in early-onset disability groups, especially those with mobility impairments. Pain is also a common complaint in adults without disability, and there is an expected response from health care providers, including intensity of evaluation and treatment. This should also be the expectation for those with disability, especially at younger ages. Any significant decrease or loss of motor skill, change in continence, change in typical activities, direct pain complaint, or “sluggishness” (39) requires further evaluation. Common musculoskeletal etiologies include poor ergonomics and biomechanics in tasks (secondary to deformity or limited motor control), underlying weakness and therefore overuse, hypertonia depending on the primary disability, and degenerative joint disease. Neurologic etiologies may also need to be considered, including general neuropathies, focal neuropathies (eg, carpal tunnel syndrome, ulnar entrapments), radiculopathies, and myelopathy or stenosis. Appropriate evaluation should be completed to determine the treatment strategy. Typical treatment strategies should be implemented and modified as needed, given the disability and improvement noted. Management may include traditional noninvasive interventions (eg, analgesics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], therapy modalities, massage), more aggressive pain management strategies (eg, manual medicine, trigger point injection, spinal injections), and re-evaluation of functional activities or positioning that may predispose to the pain complaints. For spasticity-related problems, use of tone management techniques can be helpful, including oral antispasticity medications, use of botulinum toxin injections for focal problems, or intrathecal baclofen. Surgical interventions should also be considered, and will require preplanning for rehabilitation, living arrangements, supports postprocedure, and above all good outcome evaluation. There are anticipated health and performance changes with aging. The risk for additional health problems should be monitored and addressed as with the general population. However, people with disability are often not afforded typical screening as in the general population. Iezzoni et al reported those with mobility impairments did receive pneumonia and flu vaccines, but were less likely to receive other preventive services. Women with severe mobility impairments in particular were less likely to receive Pap smears and mammography screenings (40). Cryptorchidism in males may be missed if examination is dependent on standing for examination. Women with disabilities had less knowledge about cardiovascular risks and no screening for risk factors, despite their higher risk with low activity levels (41). However, Cooper described a minor modification in office-screening techniques for adults with intellectual disability (ID) that improved the identification of risk factors and health needs, with improved health determinants (42). Lennox has shown that a Comprehensive Health Assessment Program (CHAP) resulted in increased health promotion, disease prevention, and case-finding in both community living and supported living adults with ID (43). Additional health risks and conditions can affect general performance. Performance changes with aging include decrease in strength, balance, flexibility, coordination, and cardiopulmonary function, to name a few. The impact of these known aging changes on a person with mobility impairment is not well understood. Use of equipment, modifications to environment or activities, and joint protection all contribute to maintaining function over time. It is, however, known that persons with mobility impairments use more energy to perform mobility activities than their nondisabled peers. Therefore, exercise and activity to improve performance and maintain those improvements would seem intuitively obvious. In fact, there is scientific evidence that exercise and activities are effective for people with mobility impairments and that these activities can be managed through home programs and health clubs or aquatic activities, not just traditional physical therapy programs (44,45). Simply continuing typical activities, even though considered “strenuous,” will not increase strength, conditioning, or performance. Exercise and activities should be a part of a health maintenance program for adults with mobility impairments. Participation (eg, social engagement, life role, employment) is one of the constituent elements of health and is increasingly considered a fundamental rehabilitation and health promotion outcome for child-onset disability. This is an important aspect of health and performance that should be queried when evaluating adults with pediatric-onset disability. We now have increasing generations of adults with childhood-onset disability who have the same aspirations and rights to participate fully in society. The literature on the unique needs and experiences of people with childhood-onset disability has taught us that we need to focus on physical, social, cognitive, and emotional aspects of health, with participation as one of the ultimate measures of outcome (ie, involvement in a life situation) (46). There is strong evidence that participation contributes to children’s physical, mental, and social well-being and to their QOL (47), and there is no reason to assume that this will be different when these children develop and live an adult life. Youth with physical disability, speech and language delay, or developmental disorders are at risk for lower community participation and social isolation, since they do not experience the widening social world of other teens (48). Tan et al (3) found that younger age, severe physical disability, and ID are important determinants of social participation in individuals with CP. Positive social experiences from early in childhood and continuing through adulthood prepare and support individuals with pediatric-onset disability to achieve positive sexual health and adult sexual roles (49). It is through these opportunities that people with pediatric-onset disability will develop friendships and romantic relationships. The results of the National Longitudinal Transition Survey Wave 2 showed that engagement in work or time with friends was most common for youth with learning disabilities or speech, visual, or other health impairments compared to other disabilities; more than three-fourths of youth in these categories were engaged in some type of employment including part-time jobs and unpaid volunteer work (50). In contrast, youth with ID (52%), multiple disabilities (54%), ASD (56%), and orthopedic impairment (59%) had the lowest rates of engagement. There is increasing information about specific early-onset disability conditions and adults’ health and expectations for functional performance with aging. This chapter will highlight those conditions commonly managed by pediatric physiatrists, or those for which we have useful information. There is actually considerable information available for clinicians; however, it is important to recognize the quality of the study or report (eg, case series, a convenience cohort with single-point assessments, or registry data with standardized intake and follow-up). Nonetheless, it does begin to provide a picture of the health of adults with childhood-onset conditions and the need for modifications to our health monitoring and interventions for some conditions. Table 21.2 identifies the more common health conditions and management strategies for the disabilities described in this chapter. CEREBRAL PALSY CP is the most common condition that pediatric physiatrists manage, although it is not the most common reason for childhood disability, as noted earlier. Recent estimates from the United Cerebral Palsy Association indicate that there are about 750,000 or more people in the United States with CP. Over the past 10 years, there has been increasing information available about the life course in CP, and adult issues and health are better defined. The health of adults with CP is generally good. Although CP may affect multiple organ systems, in general, long-term health problems are related to physical impairments such as pain, fatigue, and the musculoskeletal system as well as mental health issues such as depression and anxiety (see Table 21.2). Mortality Mortality for people with CP appears to be related to severity of impairments. This is very clear in the pediatric population, but less so for adults who have survived into their late twenties and thirties. In a recent study in Sweden, Westbom et al showed that virtually all children with good motor abilities, and 96% of the whole population of children with CP, survived into adulthood. Although the risk of death is the highest in fragile children with CP, their estimated survival is 60% at 19 years of age (11). There is also an obvious cohort bias when comparing mortality data from those born prior to the 1980s to mortality data of a younger adult population, and it is not clear that the information about the adults of today may be used specifically for predicting life expectancies. Through a large database in California defined by financial and service support needed and especially representative of the more severely impaired individuals with CP, survival of higher-functioning adults was close to that of the general population (51). Strauss et al also reported with this same database that older subjects who had lost the ability to walk by age 60 years had poorer survival and that those who had the most severe disabilities rarely survived to age 60 years (52). This group has found a trend toward improved survival continuing over the past 3 decades, highlighting improved care for the most fragile individuals with high levels of impairment, including use of gastrostomy tubes (53,54). The mortality ratio for most adolescents and adults with CP, relative to the general population, has increased at 1.7% (95% CIs [1.3, 2.0]) per year during the recent study period (1983–2010), while a decline in childhood mortality was noted. Life expectancies for adolescents and adults are lower for those with more severe limitations in motor function and feeding skills, and decreases with advancing age. Life expectancies for tube-fed adolescents and adults have increased by 1 to 3 years, depending on age and pattern of disability, over the past 20 years (55). Reports from countries other than the United States also identify life expectancies for adults with CP to be close to the general population for those with mild to moderate impairments. The Western Australia Cerebral Palsy Registry noted the strongest single predictor of mortality was ID (56). This study noted motor impairment severity increased the risk of early mortality, with mortality declining after age 5 to 15 years, and remaining steady at 0.35% for the next 20 years. Providing insights on era of disability onset, Hemming et al reported on adults with CP in the 1940 to 1950 birth cohort in the United Kingdom. Assuming survival to age 20 years, almost 85% survived to age 50 years compared to 96% of the general population (57). Again comparing to the general population, many of the deaths noted in the age range 20s to 30s were respiratory, and deaths in 40s to 50s were as a result of circulatory conditions and neoplasms. Few deaths in adulthood were directly attributed to CP, although the nervous system was implicated more than in the general population. The notion of increased neoplasm as the cause for death rates is echoed by the large California database noting a three-times-higher rate for breast cancer in CP than in the general population, and this may be related to severity as well as poor screening (58). Survival rates for children of today may not necessarily be extrapolated from any of these studies. Health and Quality of Life The general health of adults with CP is self-reported as good or satisfactory to excellent (59,60), and this can be comparable to that of the community at large (34). In a population-based study of adults with CP in a mid-sized U.S. metropolitan area, persons with CP were generally healthy (based on clinical information and self-report), but noted worries and concerns about their health status and future (61). Self-perceived health ratings and life satisfaction may be related to the presence of pain or functional changes over time, but not to the severity of impairment (62–64). A cross-sectional study of youth and young adults with CP in Canada using standardized measures noted youth were somewhat more positive about their health than young adults, although QOL scores were similar. Severity of CP was a strong predictor of health and QOL. Similarities between the groups were notable suggesting self-reported health and QOL outcomes may remain relatively stable across the transition to adulthood (65). HRQOL also remains fairly stable over time for people with CP. As individuals with CP grow and mature, many changes take place in their psychosocial development, which accordingly changes their expectations and those of their caregivers, peers, and professionals. The functional effect of CP seems particularly predictive of physical HRQOL, whereas the associated ID may affect their HRQOL in social functioning (2). TABLE 21.2 AGING HEALTH AND PERFORMANCE CHANGES COMMON RELATED HEALTH CONDITIONS PREVENTION STRATEGIES TREATMENT STRATEGIES Pain Fatigue Routine exercise Exercise prescription Musculoskeletal Monitor and query routinely Focal musculoskeletal evaluation Tone management Modify equipment, workplace, biomechanics of function Therapy prescription Adjust orthoses and wheelchair Bone health Routine exercise, especially weight-bearing DXA evaluation Consider treatment when multiple fractures Exercise when appropriate Neurologic Routine monitoring Adjust medications with reported change Query for changes—high index of suspicion for pathology Tone management—medications, botulinum toxin injections, intrathecal baclofen Seizure management Radiological evaluation Electrodiagnosis Surgical referral when appropriate Genito/urinary conditions Monitor and query routinely Routine gynecologic follow-up for women and follow-up for men Urodynamic evaluation Scans/radiographs Medications and CIC when needed Urology referral as appropriate Cardiovascular health Monitor blood pressure and typical serum panels Query for risk factors Treat cardiovascular symptoms and events Obesity/overweight Healthy nutrition and weight management Measurement of body fat—consider waist circumference, DXA, or BIA Monitor for metabolic syndrome symptoms/signs Manage weight; promote exercise Respiratory conditions Routine monitoring Immunization Query sleep hygiene Scoliosis evaluation Sleep study and management Specialty referral as needed Gastrointestinal Monitor and query routinely—recognition of severity Nutritional management Adjustment to bowel program regimen Oral motor problems Dental monitoring, preventive care Dental treatment Deconditioning Query about changes in function Routine exercise Education and prevention Therapy prescription—focus on strength and aerobics Reconsideration of equipment Mental health Routine monitoring, especially for depressive or anxiety symptoms Query support, living arrangements Specialty referral as appropriate Referral for psychological and social support Use of community resources Fertility/reproduction Interference spasticity or pain Emotional/body image Engage in discussion re: sexuality Provide education about sexuality and function—appropriate modality for cognition and function Assist with environmental modification for routine assessments as able Ensure pregnancy high-risk needs are met Following pregnancy, support may be needed in the home Health maintenance Monitoring—see Table 21.9 Abbreviations: BIA, bioelectric impedance analysis; CIC, clean intermittent catheterization; DXA, dual energy x-ray absorptiometry; ENT, Otolaryngologist; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; UTI, urinary tract infection. Health outcomes are also evaluated by the use of medical services. Despite reports of good health, a Canadian publication notes adults with CP visited outpatient physicians 1.9 times more than age-matched peers. Annual hospitalization admission rates were 10.6 times higher for adults with CP compared to their peers (66). The presence of other medical conditions is associated with increased odds of hospital or emergency department (ED) use (67). Analysis of the Canadian Institute for Health Information notes epilepsy and pneumonia are the top two reasons for hospital admissions for youth and young adults, and for young adults only, mental illness is the third most common admission diagnosis (68). Additional adult diagnoses included lower gastrointestinal (GI) problems or constipation, malnutrition or dehydration, upper GI problems, and two unique problems seen in the adult group: fractures and urinary tract infections (UTIs). These represent conditions for surveillance in an adult population of people with CP. Functional Status and Performance The functional status of adults with CP is not static over time, and with aging there can be modest decreasing function, as there is for the general population. A number of studies, both in the United States and abroad, with small to large convenient samples, have noted that about a third of subjects report modest to significant decreases in walking or self-care tasks (34,52,69–71). Changes in dressing and walking with relative sparing of other self-care or social activities were reported in two of these studies (34,52). More recent studies provide data by Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS), which allows better definition. Day et al used the large California database to determine the probabilities of loss or gain of walking skills into adulthood for those with CP (72). They noted that by age 25, there would unlikely be any improvement in walking skill and most would not change over the next 15 years, although there could be some decline. Therefore, the reason for even modest decreasing skill is not clear and may be related to progressive neurologic problems (eg, cervical spine stenosis, radiculopathy), lack of environmental modifications, pain, no access to or participation in exercise or activity programs, aging, or other medical conditions. Decreased independence (increased need for assistance) in mobility and self-care is a common complaint of adults with mobility impairments. The reasons for change are varied, and may include those related to age changes (eg, decreased endurance, flexibility, strength, or balance), progressive pathology or secondary conditions (eg, pain, contractures, spasticity, osteoporosis and fractures, stenosis), or personal choices (eg, use of powered mobility to conserve energy). The change in mobility is often a response to a secondary condition or age-related change. Falls may also be such a response. Significant change in mobility or falls should not automatically be accepted as a part of a congenital or childhood-onset disabling condition in adult years; treatable etiologies should be sought. It has been suggested through cross-sectional and convenience samples that adults with congenital or childhood-onset disability may show musculoskeletal, mental health, or performance changes typical of advanced aging earlier than their nondisabled peers (51,59,73) (7,74,75). These observations require confirmation through longitudinal controlled studies. While risk factors may predispose a person to these changes, they are, as yet, unproven. If these earlier-than-expected aging changes are confirmed, they should be considered secondary conditions. Pain and Fatigue Pain is the most consistent health condition reported by adults with CP (35,59,74,76,77). It has been reported in a number of samples of adults with CP at a variety of ages to be 30% to 80%, with activity limitation from this at greater than 50%. For this reason, it will be covered as a separate topic. Communication challenges and multiple pain etiologies complicate diagnosis and treatment. Pain in CP may be present for a variety of reasons; it may be acute, recurrent, or chronic (78). Increased spasticity, weakness, falls, or progression of contractures or deformities can result from pain, particularly when pain is not reported because of communication difficulties or severe ID. Because of the high prevalence, the health care provider should try to elicit complaints or indications of pain, and evaluation, diagnosis, and intervention should ensue (78). Pain is often the reason for a change in function, living arrangement, or social interaction. Pain is usually identified by proximity to a joint, and less often a limb. Most people report “arthritis” as the etiology of these pain complaints; however, these pains may originate from either joints or muscles. A good history and clinical exam will help sort out the issues and direct appropriate treatment. Back, leg, and hip pain complaints are common in persons with CP (79,80). There are usually more pain complaints in those with spasticity (79). It has been reported that fatigue often incites pain, and exercise most commonly relieves pain (79,81). Fatigue is a common complaint of adults with CP, and is associated with pain (74,82). It is also associated with deterioration of skills, depression, and low life satisfaction, with no association with any specific type or severity of CP. As noted, it may incite pain. The fatigue may also be associated with the reported coping strategies sometimes used for chronic pain by adults with CP (83). Sleep disruption should also be questioned since it is commonly seen with pain and fatigue. Anecdotally, the pain/fatigue complex appears to respond positively to directed pain management, good sleep hygiene, medications, and exercise. Appropriate management includes early identification of the problem and its source. Common musculoskeletal etiologies include poor ergonomics and biomechanics in tasks (secondary to deformity or limited motor control (71)), underlying weakness and therefore overuse (84), hypertonia (85), and degenerative joint disease (86). Typical management strategies should be offered, and referral for additional interventional, orthopedic, or neurosurgical consultation should be considered. However, adults with CP tend to self-manage their pain complaints (87), and for those who seek medical care, the report is minimal improvement and few options offered (88). Musculoskeletal and Neurologic Conditions CONTRACTURES. Contractures are a common secondary condition and may develop in childhood/adolescence and progress over the life span. Many individuals may have had interventions, including multiple surgeries in their life. Their impact on functional status or general health care needs is variable. Increasing contractures, particularly when associated with pain or increased spasticity, may be an indication of progressing pathology. Aging changes include decreased flexibility, and the clinician must distinguish pathologic causes of increasing contracture through appropriate diagnosis. OSTEOARTHRITIS. Because of the significant pain complaints that adults with CP report, it is often stated that there is an early onset of osteoarthritis. Conceptually, this has been explained by unusual and possibly increased forces on joints that may be malaligned and/or have deformity; these forces are associated with underlying weakness and poor selective motor control (59). In fact, health care providers often will make a presumed diagnosis of “arthritis” for pain complaints in adults with disability. Clinically, it is not surprising to find significant arthritic changes with radiographs of painful joints, and sometimes at young adult ages. However, the presence of early-onset arthritic changes has been documented by case reports, and studies that report arthritis among subjects base this information on self-report of arthritis or presence of pain. Often, the pain complaint is not evaluated fully, and may have an etiology in soft tissue injuries or problems and not degenerative changes within the joint. There may, in fact, be premature osteoarthritis, but it has not been documented definitively. Of importance is the recognition of pain, appropriate evaluation, and treatment. KNEE PATHOLOGY. Knee contractures are common in those who do not walk and in those who walk with obvious knee flexion and crouch. Not all knee contractures are painful. Tone management may improve range, function, and pain. Patella alta may develop from adolescence onwards over time, and pain or chondromalacia may result. Joint laxity may also be present. Modalities, exercise, kinesiotaping, and other interventions may be helpful. There are advocates for patellar tendon advancement surgeries, with or without distal femoral extension osteotomies, in adolescents and young adults to improve pain and restore knee function in gait, confirmed on gait analysis (97). FOOT OR ANKLE PAIN. Again from biomechanical factors, contractures and pain may develop. Typical interventions may assist including orthoses, but not all bracing or shoe inserts are helpful, and biomechanics must be taken into account. Plantar fasciitis with appropriate treatment should be considered. SPINE PATHOLOGY. In people with CP, severe motor impairment is associated with scoliosis and other deformities (98,99). Scoliosis may progress during adulthood, and those at 50 degrees or greater at skeletal maturity may deteriorate more rapidly (100). Scoliosis can cause seating and pressure problems, impaired respiratory function, and pain (85,100), and may be associated with windswept hips and pressure sores (85). It has been reported that spinal fusion improves the QOL for those with CP (101). Spinal stenosis must be ruled out whenever significant functional change is noted, particularly for change in or loss of walking skills, increased leg spasticity, change in bladder habits, neck pain, vague sensory changes, and (late) change in arm and hand function (102,103). A tethering effect on the spinal cord also may occur, resulting in cranial nerve changes. Some early reports noted a higher risk in those with an athetoid or dyskinetic component (104,105); however, more recent reports show these problems are present in spastic forms of CP as well. While it is generally held that stenosis is due to early spondylosis and compression, there may also be a predisposition to it in those with a congenitally narrow canal, especially at C4 to C5 (102,104). Diagnosis is made through imaging studies, while comparatively evoked potentials may also be helpful in determining neurologic function. Surgical decompression may prevent further, often catastrophic, loss of function, but does not ensure return of lost function, particularly in cases of long-standing compression with spinal cord atrophy. Recurrence at levels above or below surgical correction may be noted (106,107). Postoperative management planning should accommodate changes in functional capabilities and care needs. The presence of an athetoid movement component will affect postoperative spine stabilization and possibly head positioning and neck mobility. When no surgical intervention is undertaken, a frank discussion of possible respiratory compromise and the future need for ventilator assistance should be provided. PERIPHERAL NEUROLOGIC COMPRESSION. Radiculopathies may be a cause for painful complaints, and appropriate evaluation and treatment should ensue. It is most important that treatment strategies are based on the person’s history of function, that there is effective input from that person or their care provider, and that practical outcome goals are identified. Although not as common as a musculoskeletal etiology, nerve entrapment is also a cause of pain. The most common nerves and areas of entrapment as reported by adults with CP are the same as those susceptible to compression in the nondisabled population: the median nerve at the carpal tunnel and the ulnar nerve in the hand distally and at the elbow. Compression points are often related to use of crutches, transfer techniques, propelling wheelchairs, or existing deformity. Work-related or positional activities may also cause entrapments, just as in the nondisabled population. There is no reported increased incidence in CP. All hand pains or sensation changes do not represent nerve entrapment. Often, these complaints are actually problems of repetitive motion or are position-related. While they may be ascribed to carpal tunnel syndrome, they often respond poorly to surgery (108). Appropriate testing (including electrodiagnostic testing) is necessary to determine their etiology. Where treatment options are similar for disabled and nondisabled adults, some modification of management will be required if functional independence is changed by or during treatment. OSTEOPOROSIS. Osteoporosis has been documented in at least 50% of children and adults with CP (109). The aging process may exacerbate this issue, as does anticonvulsant use and mobility impairment. Fractures were noted to be common reasons for hospital admission (68). Pathologic fractures occur typically in the long bones, but frequency data vary and no large studies of people with CP have been reported. Low serum 25-OH vitamin D concentrations are not identified as a cause in most cases described in the literature (110). Typical screening devices or schema do not accurately identify osteoporosis risk in women with disability (111); therefore, bone mineral density testing and counseling on fall risk are important for both women and men with disability. Dual energy x-ray absorption (DXA) scans must be read with caution, since contractures often skew results. The recommendation is to use the scan results of the distal femur, as is used in children with CP and contractures (112). Use of bisphosphonates is described, but the functional improvement derived from these drugs over the long term is unknown. Additional Health Conditions There are no comorbidities known to be associated with CP. As noted, general health is good. Little is reported about cardiovascular health outcomes or risk factors such as reduced habitual physical activity levels and/or increased sedentary time in adults with CP. A study of adults living in group homes from upstate New York notes increasing health conditions with age for adults with CP as would be expected: cardiovascular, respiratory, and hearing/vision (113); this has been replicated in Taiwan and Israel (114,115). Of interest is that in comparison to U.S. national norms, there are fewer cardiovascular risk factors than seen in the general population. Peterson et al postulate that it is possible that adults with CP age more quickly than their healthy peers, resulting in an earlier onset of cardiovascular disease (CVD) (75). Either this is a healthier population or, more likely, there has not been effective screening and monitoring. Longitudinal research is necessary to determine risk factors and causation of cardiovascular events in aging adults with CP. In looking more critically at this population, the severity of the CP was related to increasing health problems with aging more than the diagnosis of CP alone (116). Vision and hearing problems may have been present early, and as anticipated, there is an increase in vision and hearing problems with age (113). Dental issues are reported for adults with CP (79). Medications, nutrition problems, poor dental hygiene, and difficulty with access to dental care all contribute to the ongoing problems into adulthood. Previously known associated conditions persist into adulthood. Dysphagia continues, and monitoring is required. Constipation also persists, and adjustments to bowel programs may be needed, in particular in individuals with more severe CP (117). From the latter study in children we can learn laxative use is high but dosing is frequently inadequate to prevent symptoms. Gastroesophageal reflux is often reported, but has not been present at increased rates. Intestinal obstruction is reportedly common in CP, and in an upstate New York cohort living in group homes, adults with CP had an increased rate compared to other adults with developmental disability (DD) (116). Urinary incontinence may also continue, and it must be ensured that there is no dyssynergia or overflow with retention (118). Rosasco et al reported adults with CP had a higher incidence of UTIs that was related more to severity than the presence of CP (116), compared to other adults with DD living in group homes in upstate New York. UTI has been found to be a common reason for hospital admission for adults with CP (68). Neurogenic bladders in adults with CP are only infrequently associated with upper tract pathology (119). Some women report that incontinence consistently occurs at a particular point of their menstrual cycle, often associated with increased spasticity (120). Urinary incontinence can be effectively addressed through well-established diagnostic and intervention approaches. There are no available data that assess the adverse impact of urinary incontinence on sexual functioning and social integration in CP, but anecdotal support for this association is abundant. In both men and women, urinary incontinence should be identified and addressed, regardless of age or other conditions. Respiratory problems have been implicated as the cause of death early in life and in early adulthood. Use of vaccinations may be helpful, along with vigilance and monitoring. Respiratory problems may increase with progressive scoliosis, and aspiration from gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) or dysphagia must be recognized. Sleep disorders related to pulmonary problems should be considered with progressive scoliosis, especially with complaints of poor sleep, morning headache, or daytime sleepiness. There has been suggestion that obesity is a problem in CP, and yet studies are inconclusive (75,121). In fact, a small study of adults with CP identified mean body fat percentages and body mass indexes (BMIs) were within normal range, although 40% had heights below the fifth percentile for age and gender. Fifty-five percent reported dysphagia (122). Measurement of the percentage of body fat, which is the mark of healthy weight, is not routinely done, and state-of-the-art techniques (eg, DXA, bioelectric impedance analysis) have not been standardized for this population. Sexual Functioning Empirical data on sexual development and functioning of persons with CP are scarce. The most recent information comes from research on romantic relationships and sexual development of a well-documented cohort of mainly ambulatory persons with CP with average intelligence. About 30% of participants were found to be below their age level for dating and intimate relationships (49). Women’s sexual health and functioning is better described than men’s. Women with CP typically have limited participation in health maintenance activities such as routine pelvic examinations, Pap smears, and breast examinations (60,123). Office visit planning is required for those with significant motor impairments to ensure a complete examination. Attitudinal barriers of health care providers often limit services and education. However, women with CP are typically able to conceive and carry pregnancies to term without the expectation of major complications related to their CP. Use of contraceptives has not been well studied, and consideration of thrombotic effects must be considered in the choice of options. A commonly offered contraception is injectable nonestrogenic formulations such as depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA), although long-term effects are not well defined (120,123). DMPA can reduce bone mineral density, so may not be indicated in those with existing low bone densities or other risk factors for osteoporosis. An intrauterine device (IUD) may reduce menstrual flow and provide effective contraception, but its insertion may necessitate sedation (124). Women with CP report fewer sexual encounters as compared to other women with disability (35,125). Women with early-onset disability also experience high levels of sexual desire compared to other women with disability, postulated as being related to reduced social opportunities, frustrated satisfaction of sexual urges, discouragement of childhood sexual expression, or perceived social stereotypes (125). Men with CP also should receive information on sexual functioning, including information on contraception and protection. There have been no reported problems with fertility. Most young men with CP reported a sexual interest (fantasizing or seeking erotic material), experienced feelings of sexual arousal, although some young adults with CP, however, experienced anorgasmia (49). Men with CP have a higher incidence of cryptorchidism (53%) at the age of 21 years compared with the general population (126), but this problem can easily be missed when the testis cannot be visualized or palpated with the patient in the standing position. Adults with CP have many questions, including the use of contraception, heredity, pregnancy, assistive aids, spasticity, and pain. They also reported to have worries about interaction with a partner, experiencing a deviant body image, shame about their body, reactions of their body, and how to stimulate their partner sexually (127). The topic of sexuality does not come up easily at appointments with physicians. Young adults with CP request an active role for the physician or other health care professionals to openly communicate on sexuality and provide the necessary information (127). Topics specific to CP that should be discussed are the following (127): • Information about fertility, pregnancy, parenting • Influence of spasticity (stimulation, masturbation, orgasm, etc.) • Advice on alternative ways of making love, adapted postures • Use of specific assistive devices • Possibility of medication and operations to facilitate postures • How to ask for assistance in activities of daily living in preparation for sex • Information about sexual caregiving

Abbreviation: SE, standard error.

Source: Modified from Ref. (20). Halfon N, Houtrow A, Larson K, Newacheck PW. The changing landscape of disability in childhood.

Future Child. 2012;22(1):13–42.

Monitor and query routinely

Work simplification

Ergonomic evaluations

Energy conservation

Query/evaluate sleep; manage as needed

Evaluate for pain etiology and treat

Modify equipment or workplace

Evaluate mental health and manage

Progress to pain management program

Contractures

Hip pathology

Knee pathology

Foot or ankle pain

Back pain

Joint protection strategies

Routine exercise

Biomechanic and ergonomic assessments

Osteoporosis

Fractures

Calcium/vitamin D supplement

Fracture and fall prevention; education

Spasticity

Seizures

Spinal stenosis

Nerve entrapments

Incontinence

UTIs

Infection

Sleep apnea

Constipation

GERD

Obstruction

Specialty referral when appropriate

Drooling management, including botulinum toxin injections and possible ENT referral

Falls

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree