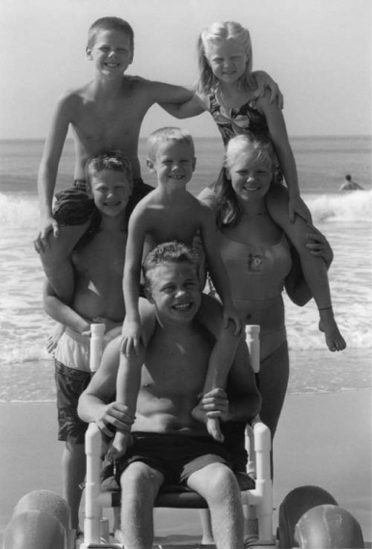

9 ADAPTIVE SPORTS AND RECREATION Michelle Miller and Ellen S. Kaitz† Adapted sports for the disabled (DA) were introduced in the mid-20th century as a tool for the rehabilitation of injured war veterans. They have developed to encompass all ages, abilities, and nearly all sport and recreational activities, from backyards to school grounds to national, international, and Paralympic competitions. The trend in recent years has led sports away from its medical and rehabilitation roots to school- and community-based programs focused on wellness and fitness, rather than on illness and impairment. However, rehabilitation professionals remain connected in a number of important ways. Sports and recreation remain vital components of a rehabilitation program for individuals with new-onset disability. Furthermore, rehabilitation professionals may be resources for information and referral to community programs. They may be involved in the provision of medical care for participants or act as advisors for classification. As always, research to provide scientific inquiry in biomechanics, physiology, psychology, sociology, technology, sports medicine, and many related issues is a necessary component. HISTORY Sports and exercise have been practiced for millennia. Organized activities for adults with disabilities have more recent roots, going back to the 1888 founding of the first Sport Club for the Deaf in Berlin, Germany. The International Silent Games, held in 1924, was the first international competition for DA athletes. Deaf sports were soon followed by the establishment of the British Society of One-Armed Golfers in 1932. Wheelchair sports are younger still, having parallel births in Britain and the United States in the mid-1940s. Sir Ludwig Guttman at the Stoke Mandeville Hospital in Aylesbury, England, invented polo as the first organized wheelchair team sport. “It was the consideration of the over-all training effect of sport on the neuro-muscular system and because it seemed the most natural form of recreation to prevent boredom in hospital …” (1). Within a year, basketball replaced polo as the principle wheelchair team sport. In 1948, the first Stoke Mandeville Games for the Paralyzed was held, with 16 athletes competing in wheelchair basketball, archery, and table tennis. This landmark event represented the birth of international sports competition for athletes with a variety of disabilities. The games have grown steadily, now comprising more than two dozen different wheelchair sports. The competitions are held annually in non-Olympic years, under the oversight of the International Stoke Mandeville Wheelchair Sport Federation (ISMWSF). While Guttman was organizing wheelchair sports in Britain, war veterans in California played basketball in the earliest recorded U.S. wheelchair athletic event. The popularity flourished, and, a decade later, the first national wheelchair games were held. These games also included individual and relay track events. With the success of these games, the National Wheelchair Athletic Association (NWAA) was formed. Its role was to foster the guidance and growth of wheelchair sports. It continues in this role today under its new name, Wheelchair Sports USA. The U.S. teams made their international debut in 1960 at the first Paralympics in Rome. The term “Paralympic” actually means “next to” or “parallel” to the Olympics. In the 54 years since, the number and scope of sport and recreational opportunities has blossomed. The National Handicapped Sports and Recreation Association (NHSRA) was formed in 1967 to address the needs of winter athletes. It has more recently been reorganized as Disabled Sports USA (DS/USA). The 1970s saw the development of the United States Cerebral Palsy Athletic Association (USCPAA) and United States Association for Blind Athletes (USABA). In 1978, Public Law 95–606, the Amateur Sports Act, was passed. It recognized athletes with disabilities as part of the Olympic movement and paved the way for elite athletic achievement and recognition. In the 1980s, a virtual population explosion of sport and recreation organizations occurred. Examples of these organizations include the United States Amputee Athletic Association (USAAA), Dwarf Athletic Association of America (DAAA), and the United States Les Autres Sports Association (USLASA; an association for those with impairments not grouped with any other sports organizations), the American Wheelchair Bowling Association (AWBA), National Amputee Golf Association (NAGA), United States Quad Rugby Association (USQRA), and the Handicapped Scuba Association (HSA). Internationally, the International Paralympic Committee (IPC) was created in 1989 as a nonprofit organization, headquartered in Bonn, Germany, to organize the summer and winter Paralympic games, promote the Paralympic values, and encourage participation in disabled sports from the beginner to the elite level. It also acts as the international federation for nine sports and oversees worldwide championships in these sports. It recognizes four additional International Organizations of Sports for the Disabled (IOSDs) including the Cerebral Palsy International Sports and Recreation Association (CPISRA), the International Blind Sports Federation (IBSA), the International Sports Federation for Persons with an Intellectual Disability (INAS), and the International Wheelchair and Amputee Sports Federation (IWAS). The awareness of and appreciation for disabled athletes was especially evident in the 2012 Paralympic Games held in London. There were 4,237 athletes present from 164 countries who participated in a total of 503 events in 20 sports. During this event, 251 world records and 314 Paralympic records were set. There was a record 2.7 million spectators and millions more who watched the televised events or accessed the events through the Internet. Surveys of the British noted a significant positive change in attitude toward athletes with disabilities and disabled sports. While the history of sports for the DA can be traced back a century, the development of junior-level activities and competition can be measured only in a few short decades. The NWAA created a junior division in the early 1980s that encompassed children and adolescents from 6 to 18 years of age. It has since established the annual Junior Wheelchair Nationals. Junior-level participation and programming have been adopted by many other organizations, including the National Wheelchair Basketball Association (NWBA), DS/USA, and American Athletic Association of the Deaf (AAAD). Sports for youth with disabilities are increasingly available in many communities through Adapted Physical Education (APE) programs in schools, inclusion programs in Scouting, Little League baseball, and others. EXERCISE IN PEDIATRICS: PHYSIOLOGIC IMPACT It is widely accepted that exercise and physical activity (PA) have many physical and psychological benefits. Much research has been done to support this in adults. More recently, data has been presented to describe the benefits of exercise in both healthy children and those with chronic disease. Exercise programs in healthy children have resulted in quantifiable improvements in aerobic endurance, static strength, flexibility, and equilibrium (2). Regular PA in adolescence is associated with lower mean adult diastolic blood pressures (3). However, a survey of middle school children showed that the majority are not involved in regular PA or physical education (PE) classes in school (4). Despite this, school days are associated with a greater level of PA in children at all grade levels than free days (5). Requiring PE classes in school improves the level of PA in children, but does not lower the risk for development of overweight or obesity (6) without dietary education and modification (7). Children attending after-school programs participate in greater amounts of moderate and vigorous PA than their peers (8). Obesity is increasing in epidemic proportions among children in developed countries. It has been linked to development of the metabolic syndrome (defined as having three or more of the following conditions: waist circumference ≥ 90th percentile for age/sex, hyperglycemia, elevated triglycerides, low- and high-density lipoprotein [HDL] cholesterol, and hypertension) (9); both obesity and metabolic syndrome are more common in adolescents with lower levels of PA (10). Insulin resistance is reduced in youth who are physically active, reducing the risk of developing type 2 diabetes (11). Exercise in obese children can improve oxygen consumption and may improve cardiopulmonary decrements, including resting heart rate (12). An 8-week cycling program has been shown to improve HDL levels and endothelial function (13), though in the absence of weight loss, had little effect on adipokine levels (14). Exercise has positive effects on bone mineralization and formation. Jumping programs in healthy prepubescent children can increase bone area in the tibia (15) and femoral neck, and bone mineralization in the lumbar spine (16). The effects of exercise and weight-bearing may be further enhanced by calcium supplementation (17). The effects on postpubertal teens are less clear. In children with chronic physical disease and disability, the beneficial effects of exercise are beginning to be studied more systematically. Historically, it was believed that children with cerebral palsy (CP) could be negatively impacted by strengthening exercises, which would exacerbate weakness and spasticity. Recent studies show this to be untrue. Ambulatory children with CP who participate in circuit training show improved aerobic and anaerobic capacity, muscle strength, and health-related quality-of-life scores (18). In ambulatory adolescents with CP, circuit training can reduce the degree of crouched gait and improve perception of body image (19). Performing loaded sit-to-stand exercises results in improved leg strength and walking efficiency (20,21). Percentage body fat is greater, and aerobic capacity (VO2/kg) is lower in adolescents with spinal cord dysfunction than healthy peers. Their levels mirror those in overweight peers. They also reach physical exhaustion at lower workloads than unaffected controls (22). Participation in programs such as BENEfit, a 16-week program consisting of behavioral intervention, exercise, and nutrition education, can produce improvements in lean body mass, strength, maximum power output, and resting oxygen uptake (23). Supervised physical training can safely improve aerobic capacity and muscle force in children with osteogenesis imperfecta (24). Patients with cystic fibrosis who participate in stationary cycling for aerobic conditioning dislike the tedium of the exercise, but improve their muscle strength, oxygen consumption, and perceived appearance and self-worth (25). Pediatric severe-burn survivors have lower lean body mass and muscle strength compared with nonburned peers; however, both are significantly improved following exercise training (26). Children with polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis have safely participated in aerobic conditioning programs, with improvements noted in strength and conditioning. Those with hip pain may be negatively impacted, having increased pain and disability (27). The exercise prescription in children experiencing hip pain should be modified to reduce joint forces and torques. Joint hypermobility and hypomobility syndromes commonly result in pain. These patients demonstrate lower levels of physical fitness and higher body mass indexes, likely secondary to deconditioning (28). These and other children with pain syndromes benefit from increased exercise and PA. EXERCISE IN PEDIATRICS: PSYCHOSOCIAL IMPACT The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services published in 2010 that 31% of children (ages 4–11) were reported to be sad, unhappy, or depressed compared with 17% of children without disabilities (29). Regular PA in early childhood through adolescence fosters not only improvements in physical health, but also psychosocial health and development (30,31). The amount and quality of PA have significantly declined over the past several decades and even able-bodied (AB) children are no longer meeting the recommended guideline of 1 hour or more of moderate-intensity PA on 5 or more days a week (32). In disabled children, the amount of PA is even more restricted due to a variety of factors, including the underlying disability, physical barriers, and availability of resources (33). Sit et al. noted that the amount of time spent by children in moderate PA at school during PE and recess was lowest for children with a physical disability, at 8.9%, and highest for children with a hearing loss, at 16.6% of recommended weekly minutes (34). Studies involving AB children have demonstrated that providing game equipment and encouragement from teachers can significantly increase moderate activity levels during recess (35). Deviterne et al. reported that providing participant-specific written and illustrated instruction concerning sporting activities such as archery to adolescents with motor handicaps improves their skill performance to a level similar to an AB adolescent at the end of the learning session that can foster increased self-esteem (36). Many studies have demonstrated increased social isolation with fewer friendships among disabled children and adolescents. The Ontario Child Health Study revealed that children with a chronic disability had 5.4 times greater risk of being socially isolated and 3.4 times greater risk of psychiatric problems (37). Mainstreaming seems to have a positive impact, although concerns regarding AB peer rejection are still pervasive (38). Children in integrated PE programs were more likely to view their disabled peers as “fun” and “interesting” compared to children who were not integrated (39). One study of teacher expectations in mainstreamed PE classes revealed significantly lower expectations for the disabled student’s social relations with peers (40). The attitude toward mainstreamed PE among high school students was significantly more positive in the AB group as opposed to the disabled population (41). Disabled children often view their lack of physical competence and, second, the status among their peers as the major barriers in social competence (42). In addition to regular PA, play is a major component of childhood and important in psychosocial development of children. In preschool children with developmental delay or mental retardation, they were more likely to play on their own or not participate in play compared to the typically developing peers. Placing them in an integrated playgroup increased peer interactions compared to a nonintegrated playgroup, but did not correct the discrepancy in sociometric measures (43). There have also been discrepancies noted in the type of play for children with developmental delays. These children are less likely to participate in imaginative or constructive play (ie, creating something using play materials) and more likely to participate in functional (ie, simple repetitive tasks) and exploratory play (44). It has been suggested that play should be taught, and one study by DiCarlo demonstrated that a program that taught pretend play increased independent pretend toy play in 2-year-old children with disabilities (45). Play for children with physical disabilities is also impaired. Children rely on technical aids such as bracing, walkers, wheelchairs, or adult assistants to access play areas and play equipment. Studies have shown that they are seldom invited to spontaneous playgroups and rarely take part in sporting activities unless the activity is geared toward children with disabilities (46). In a study by Tamm and Prellwitz, preschool and school children in Sweden were surveyed about how they viewed children in a wheelchair. They were willing to include disabled children in their games, but saw barriers to participation in outdoor activities due to the inaccessibility of playgrounds and the effect of weather. They did not feel children with disabilities would be able to participate in activities like ice hockey, but could play dice games. They felt sedentary and indoor activities were more accessible. The children also felt that disabled peers would have high self-esteem, although most literature has documented that disabled children have low self-esteem (47). In another study, children with motor disabilities were surveyed regarding how they perceived their technical aids in play situations. Younger children viewed their braces, crutches, walkers, or wheelchairs as an extension of themselves and helpful in play situations. Older children also saw the equipment as helpful, but a hindrance in their social life, as it made them different from their peers. Both older and younger children saw the environment as a significant barrier to play. Playgrounds often had fencing surrounding the area, sand, and equipment such as swings or slides that were not accessible without the assistance of an adult. The weather impacted accessibility due to difficulty maneuvering on ice or through snow. Children often took on an observational role on the playground or stayed inside. It was noted that the lack of accessibility sent the message that children with DA were not welcome and further isolated the DA group. As far as adult assistance, the younger children often incorporated the adult as a playmate. As children became older, they viewed their adult assistants as intrusive and a hindrance in social situations. Older children often chose to stay at home and be alone rather than going somewhere with an adult (46). The research has highlighted many areas for improvement in accessibility for play and social interaction. Several articles detail ways to create accessible playgrounds, and these playgrounds are now becoming more prevalent in the community (Figure 9.1). Playground surfaces can be covered with rubber, and ramps can be incorporated throughout the play structure to allow access by wheelchairs, walkers, and other assistive devices. Playground equipment can include wheelchair swings and seesaws that allow a wheelchair placement (48). FIGURE 9.1 Playground equipment can be adapted to include children of all abilities, including pathways for wheelchair and walker access. ADAPTED SPORTS AND RECREATION PROFESSIONALS A variety of fields provide training and expertise in adapted sports, recreation, and leisure. They include APE teachers, child life specialists, and therapeutic recreation (TR) specialists. Physical and occupational therapists often incorporate sports and recreation into their treatment plans as well. However, their involvement remains primarily within a medical framework and will not be discussed here. APE developed in response to the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), which states that children with disabling conditions have the right to free, appropriate public education in the least restrictive environment. Included in the law is “instruction in physical education,” which must be adapted and provided in accordance with the Individualized Education Program (IEP). APE teachers receive training in identification of children with special needs, assessment of needs, curriculum theory and development, instructional design, and planning, as well as direct teaching (49,50). The APE National Standards (51) were developed to outline and certify minimum competency for the field in response to only 14 states developing standards for APE following the passage of the IDEA. APE teachers provide some of the earliest exposure to sports and recreation for children with special needs, and introduce the skills and equipment needed for future participation. TR has its roots in recreation and leisure. It provides recreation services to people with illness or disabling conditions. Stated in the American Therapeutic Recreation Association Code of Ethics, the primary purposes of treatment services are “to improve functioning and independence as well as reduce or eliminate the effects of illness or disability” (52). Clinical interventions used by TR specialists run the gamut, from art, music, dance, and aquatic therapies to animal, poetry, humor, and play therapy. They may include yoga, tai chi chuan, aerobic activity, and adventure training in their interventions. While some training in pediatrics is standard in a TR training program, those who have minored in child life or who have done internships in pediatric settings are best suited for community program development. TR specialists are often involved in community-based sports for those with DA, serving as referral sources, consultants, and support staff. Child life is quite different from TR. Its roots are in child development and in the study of the impact of hospitalization on children. Its focus remains primarily within the medical/hospital model, utilizing health care play and teaching in the management of pain and anxiety and in support. Leisure and recreation activities are some of the tools utilized by child life specialists. Unlike TR specialists, child life workers focus exclusively on the needs and interventions of children and adolescents. There is often overlap in the training programs of child life and TR specialists. The role of the child life specialist does not typically extend to community sports and recreation programs. PARTICIPATION IN PHYSICAL ACTIVITY A number of scales have been developed to measure participation in activities. One example is the World Health Organization Health Behavior in School-Aged Children (WHO HBSC) survey. It is a self-reported measure of participation in vigorous activity that correlates well with aerobic fitness and has been shown to be reliable and valid (53). The Previous Day PA Recall (PDPAR) survey has been shown to correlate well with footsteps and heart rate monitoring, and may be useful in assessing moderate-to-vigorous activity of a short time span (54). The PA Scale for Individuals with Physical Disabilities (PASIPD) records the number of days a week and hours daily of participation in recreational, household, and occupational activities over the past 7 days. Total scores can be calculated as the average hours daily times a metabolic equivalent value and summed over items (55). The Craig Hospital Inventory of Environmental Factors (CHIEF) is a 25-item survey that identifies presence, severity, and frequency of barriers to participation, and is applicable to respondents of all ages and abilities. A 12-item short form, CHIEF-SF is also available. When applied to a population with diverse disabilities, the CHIEF measure revealed the most commonly identified barriers to participation are weather and family support (56). Pediatric measures include CAPE, which stands for Children’s Assessment of Participation and Enjoyment. This tool has been validated in AB and DA children aged 6 to 21 years. It is used in combination with the PAC, the Preferences for Activities of Children. Together, they measure six dimensions of participation (ie, diversity, intensity, where, with whom, enjoyment, and preference) in formal and informal activities and five types of activities (recreational, active physical, social, skill-based, and self-improvement) without regard to the level of assistance needed. The scales can be used to identify areas of interest and help develop collaborative goal setting between children and caregivers. Identification of interests and barriers can facilitate problem solving and substitution of activities fulfilling a similar need (57). The European Child Environment Questionnaire (ECEQ) has been used to show that intrinsic and extrinsic barriers are equally important in limiting PA among DA youth (58). Using these and other measures, one finds that participation in PA varies widely, even among nondisabled populations. The Third National Health and Nutrition Examination survey found that the prevalence of little to no leisure-time PA in adults was between 24% and 30% (59). The groups with higher levels of inactivity included women, older persons, Mexican Americans, and non-Hispanic Blacks. A number of factors have been positively associated with participation in healthy adults, including availability and accessibility of facilities, availability of culture-specific programs, cost factors, and education regarding the importance of PA. Likewise, in healthy adolescents, PA is less prevalent among certain minorities, especially Mexican Americans and non-Hispanic Blacks. Participation in school-based PE or community recreation centers is positively correlated with PA, as are parental education level and family income (60). Paternal PA, time spent outdoors, and attendance at nonvocational schools are more common among children with higher levels of PA (61). Access to parks increases participation, especially in boys. Lower levels of moderate or vigorous PA are seen in those who reside in high-crime areas (62). When followed over time, adolescents tend to decrease their participation in PA from elementary to high school. Boys who are active have a tendency to pursue more team sports, whereas girls are more likely to participate in individual pursuits (63). Coaching problems, lack of time, lack of interest, and limited awareness have been cited as other barriers to PA (64). Overall, however, informal activities account for more participation in children and teens than formalized activities (65). Ready access to technology is associated with a decline in healthy children’s participation in PA. Television viewing is inversely related to activity levels and positively correlates with obesity, particularly in girls (66). Increased computer time is also related to obesity in teenage girls (67). Interestingly, playing digital games has not been linked with obesity, and active video games have, in fact, increased levels of PA among children and adolescents (68–70). It is not surprising to learn that many of the barriers to PA identified by AB are the same as those experienced by children with DA. The most commonly cited are lack of local facilities, limited physical access, transportation problems, attitudinal barriers by public and staff, and financial concerns. Lack of sufficiently trained personnel and of appropriate equipment have also been identified (33,71,72). Among those children with severe motor impairments, the presence of single-parent household, lower family income, and lower parent education are significant barriers (65). Pain is more frequently reported in children with CP and interferes with participation in both activities of daily living (ADLs) and PA (73). The presence of seizures, intellectual impairment, impaired walking ability, and communication difficulties predicts lower levels of PA among children with CP (74). Many children are involved in formal physical and occupational therapy. Therapists as a whole have been limited in their promotion of recreation and leisure pursuits for their pediatric clientele (75). Therapy sessions and school-based programs provide excellent opportunities for increasing awareness of the need and resources available for PA. Policy and law changes related to the Americans with Disabilities Act are resulting in improved access to public facilities and transportation. Many localities are providing adapted programs and facilities that are funded through local taxation (Figure 9.2). Impairment-specific sports have grown from grassroots efforts, often with the assistance or guidance of rehabilitation professionals. Organizations such as BlazeSports (www.blazesports.org) have developed programs throughout the United States. The bedrock of BlazeSports America is made up of the community-based, year-round programs delivered through local recreation providers. It is open to youth with all types of physical disabilities. Winners on Wheels “empowers kids in wheelchairs by encouraging personal achievement through creative learning and expanded life experiences that lead to independent living skills.” Chapters exist in many cities across the United States and incorporate PA into many of the activities they sponsor. The American Association of Adapted Sports Programs (AAASP) employs athletics through a system called the adaptedSPORTS model. “This award-winning model is an interscholastic structure of multiple sports seasons that parallels the traditional interscholastic athletic system and supports the concept that school-based sports are a vital part of the education process and the educational goals of students” (www.adaptedsports.org). The sports featured in the adaptedSPORTS model have their origin in Paralympic and adult disability sports. The program provides standardized rules for competition, facilitating widespread implementation. Application in the primary and high school levels can help students develop skills that can lead to collegiate-, community-, and elite-level competition. FIGURE 9.2 Many public facilities have wheelchairs available for rent or use that are designed for use on the beach. In some communities, AB teams or athletes have partnered with groups to develop activity-specific opportunities. Fore Hope is a nationally recognized, nonprofit organization that uses golf as an instrument to help in the rehabilitation of persons with disabilities or an inactive lifestyle. The program is facilitated by certified recreational therapists and golf professionals (www.forehope.org). A similar program known as KidSwing is available to DA children in Europe and South Africa (www.kidswing-international.com). Several National Football League (NFL) players have sponsored programs targeting disabled and disadvantaged youth. European soccer team players have paired with local organizations to promote the sport to DA children. Financial resources are also becoming more available. The Challenged Athletes Foundation (CAF) supports athletic endeavors by providing grants for training, competition, and equipment needs for people with physical challenges. Athletes Helping Athletes (www.athleteshelpingathletesinc.com) is a nonprofit group that provides handcycles to children with disabilities at no cost. The Golden Opportunities fund (www.dsusa.org) provides support and encouragement to DA youth in skiing. More resources can be found at the Disaboom website (vcelkaj.wix.com/disaboom). INJURIES IN DISABLED ATHLETES With more DA athletes come more sports injuries. The field of sports medicine for the disabled athlete is growing to keep pace with the increase in participation. Among elite athletes in the 2002 Winter Paralympics, 9% sustained sports-related injuries. Sprains and fractures accounted for more than half of the injuries, with strains and lacerations making up another 28% (75). Summer Paralympians sustained sprains, strains, contusions, and abrasions rather than fractures or dislocations (76). Retrospective studies have shown a 32% incidence of sports injuries limiting participation for at least a day. Special Olympics participants encounter far fewer medical problems than their elite counterparts. Of those seeking medical attention during competition, overall incidence is under 5%, with nearly half related to illness rather than injury. Knee injuries are the most frequently reported musculoskeletal injury. Concerns regarding atlantooccipital instability and cardiac defects must be addressed in the participant with Down syndrome. Among elite wheelchair athletes, upper limb injuries and overuse syndromes are common; ambulatory athletes report substantially more lower limb injuries. Spine and thorax injuries are seen in both groups (77). Wheelchair racers, in particular, report a high incidence of arm and shoulder injuries. The injuries do not appear to be related to distance, amount of speed training, number of weight-training sessions, or duration of participation in racing (78). A survey of pediatric wheelchair athletes reveals that nearly all children participating in track events report injuries of varying degrees. Blisters and wheel burns are most frequent, followed by overheating, abrasions, and bruising. Shoulder injuries account for the majority of joint and soft tissue complaints. Injuries among field competitors are less frequent, with blisters and shoulder and wrist problems reported most often. Swimmers report foot scrapes and abrasions from transfers, suggesting opportunity for improved education regarding skin protection (79). An important factor in injury prevention for the wheelchair athlete is analysis of and instruction in ergonomic wheelchair propulsion (80). Proper stroke mechanics positively affect pushing efficiency. Push frequency also affects energy consumption and can be adjusted to improve athletic performance (81). Motion analysis laboratories and Smartwheel technology can be utilized to objectively analyze and help improve pushing technique, thus reducing injury (82). While some injuries are sport-specific, others may be more common among participants with similar diagnoses. Spinal-cord-injured individuals are at risk for dermal pressure ulcer development, thermal instability, and autonomic dysreflexia. In fact, some paralyzed athletes will induce episodes of dysreflexia, known as “boosting,” in order to increase catecholamine release and enhance performance (83). Education regarding the risks of boosting is essential, as are proper equipment and positioning to protect insensate skin. Athletes with limb deficiencies may develop painful residual limbs or proximal joints from repetitive movements or ill-fitting prostheses. The sound limb may also be prone to injury through overuse and asymmetric forces (84). Participants with vision impairments sustain more lower limb injuries than upper limb injuries, while those with CP may sustain either. Spasticity and foot and ankle deformities in children with CP may further predispose them to lower limb injury. As with all athletes, loss of range of motion, inflexibility, and asymmetric strength further predispose the DA participant to injury. Instruction in stretching, strengthening, and cross-training may reduce the incidence and severity of injury. “EVENING THE ODDS”: CLASSIFICATION SYSTEMS Sport classification systems have been developed in an attempt to remove bias based on innate level of function. In theory, this would allow fair competition among individuals with a variety of disabilities. Early classifications were based on medical diagnostic groupings: one for athletes with spinal cord lesion, spina bifida, and polio (ISMWSF); one for ambulatory amputee athletes and a separate one for amputee athletes using wheelchairs; one for athletes with CP; one for les autres (International Organizations of Sports for the Disabled [IOSD]), and so forth. These early attempts reflected the birth of sports as a rehabilitative tool. This form of classification continues to be used in some disability-specific sports, such as goalball for blind athletes and sit volleyball for amputee athletes. Other older systems took into account degree of function. This system unfairly penalized athletes who were more physically fit, younger, more motivated, and so forth. The most recent IPC regulations recognize ten specific impairment types as eligible for participation. They are as follows: • Impaired muscle power: Impairments in this category have in common that there is reduced force generated by the contraction of a muscle or muscle groups (eg, muscles of one limb, one side of the body, the lower half of the body). Examples of conditions included in this category are para- and quadriplegia, muscular dystrophy, postpoliomyelitis, and spina bifida. • Limb deficiency: There is a total or partial absence of the bones or joints as a consequence of trauma (eg, traumatic amputation), illness (eg, bone cancer), or congenital limb deficiency (eg, dysmelia). • Leg length difference: Due to congenital deficiency or trauma, bone shortening occurs in one leg. • Short stature: Standing height is reduced due to aberrant dimensions of bones of upper and lower limbs or trunk (eg, achondroplasia). • Hypertonia: A condition marked by an abnormal increase in muscle tension and a reduced ability of a muscle to stretch. Hypertonia may result from injury, disease, or conditions that involve damage to the central nervous system. When the injury occurs in children under the age of 2, the term cerebral palsy is often used, but it also can be due to brain injury (eg, stroke, trauma) or multiple sclerosis. • Ataxia: Ataxia is a neurologic sign and symptom that consists of a lack of coordination of muscle movements. When the injury occurs in children under the age of 2, the term cerebral palsy is often used, but it also can be due to brain injury (eg, stroke, trauma) or multiple sclerosis. • Athetosis: Athetosis can vary from mild to severe motor dysfunction. It is generally characterized by unbalanced, involuntary movements of muscle tone and a difficulty maintaining a symmetrical posture. When the injury occurs in children under the age of 2, the term cerebral palsy is often used, but it also can be due to brain injury (eg, stroke, trauma). • Vision impairment: Vision is impacted by either an impairment of the eye structure, optical nerves or optical pathways, or visual cortex of the central brain. • Intellectual impairment: The IPC further recognizes the necessity of sport-specific classification systems. To ensure competition is fair and equal, all Paralympic sports have a system in place, which ensures that winning is determined by skill, fitness, power, endurance, tactical ability, and mental focus, the same factors that account for success in sport for AB athletes. The purpose of classification is to minimize the impact of impairments on the activity (sport discipline). Thus having the impairment is not sufficient. The impact on the sport must be proved, and in each Paralympic sport, the criteria of grouping athletes by the degree of activity limitation resulting from the impairment are named “Sport Classes.” Through classification, it is determined which athletes are eligible to compete in a sport and how athletes are grouped together for competition. This, to a certain extent, is similar to grouping athletes by age, gender, or weight. Classification is sport-specific because an impairment affects the ability to perform in different sports to a different extent. As a consequence, an athlete may meet the criteria in one sport, but may not meet the criteria in another sport (IPC, 2007). ADAPTING RECREATION OPPORTUNITIES Camping Camping, mountaineering, and hiking are among the many outdoor adventure activities available to children with disabilities. The National Park Service maintains information on park accessibility and amenities across the United States. The America the Beautiful—National Parks and Federal Recreation Lands Pass is available to any blind or permanently disabled U.S. citizen/permanent resident, and allows free lifetime admission to all national parks for the individual and up to three accompanying adults. Accompanying children under the age of 16 are admitted free of charge. It is obtained at any federal fee area or online at http://store.usgs.gov/pass and allows a 50% reduction in fees for recreation sites, facilities, equipment, or services at any federal outdoor recreation area. Boy and Girl Scouts of America each run inclusion programs for children with disabilities. Opportunities also exist in dozens of adventure and specialty camps across the United States. Some are geared to the disabled and their families, allowing parallel or integrated camping experiences for disabled children. Participation requires few adaptations, and the Americans with Disability Act has been instrumental in improving awareness in barrier-free design for trails, campsites, and restrooms. Parents should evaluate the camps in regard to the ages of the participants, medical support, and cost. Often, camps are free or offer scholarships and may provide transportation. Some camps will have diagnosis-specific weeks, such as CP, spina bifida, muscular dystrophy, and so on. A nice summer camp resource is www.mysummercamps.com. There are accessible recreational vehicles (RVs) available for rent as well as purchase. Many manufacturers will customize their RVs during the production process. A number of travel clubs exist across the United States and have websites giving information on accessible campsites with an RV in mind. In addition, many have annual gatherings of their members at a chosen campsite. One good website is www.handicappedtravelclub.com. Fishing Fishing can be enjoyed by virtually anyone, regardless of ability. One-handed reels, electric reels, and even sip-and-puff controls allow independent participation. A variety of options exist for grasping and holding rods as well. These range from simple gloves that wrap the fingers and secure with Velcro or buckles to clamps that attach directly to the rod, allowing a hand or wrist to be slipped in. Harnesses can attach the rod to the body or to a wheelchair, assisting those with upper limb impairments. There are devices that assist with casting as well for individuals with limited upper body strength or control. Depending on the level of expertise and participation of the fisher, simple or highly sophisticated tackle can also be had (85,86). Both land and sea fishing opportunities are accessible to the disabled. Piers are usually ramped and may have lowered or removable rails for shorter or seated individuals. Boats with barrier-free designs offer fishing and sightseeing tours at many larger docks. These offer variable access to one or all decks, toilet facilities, and shade (85). Hunting Adaptations to crossbows and rifles have made hunting accessible for many. The crossbow handle and trigger can be modified for those with poor hand function. Stands for rifles and crossbows are also available for support. Many hunting ranges have incorporated wheelchair-accessible blinds. Dance Dancing has become more popular in the AB and disabled populations over the past 15 years. The wheelchair is considered an artistic extension of the body, and many dances have been adapted for the movement of the wheels to follow the foot patterns of classical ballroom dancing. Wheelchair dancing was first begun in 1972 and pairs DA and AB individuals in a variety of dances. Recreational opportunities and competition are available in many states, with classes including duo dance featuring two wheelchair dancers together, group dancing of AB and wheelchair competitors in a synchronized routine, and solo performances. Wheelchair dance sport has been a recognized sport within the Paralympics since 1998, although it is not currently included in the program. International competition in wheelchair dance has been around since 1977. In addition, ballet, jazz, and modern dance companies offer inclusion for children with disabilities. Martial Arts Martial arts classes include children with a variety of disabilities. The classes can be modified to allow skills at the wheelchair level in forms, fighting, weapons, and breaking. Children are taught self-respect, control, and can advance through the belt system. They are also taught basic self-defense in some settings. There are many different styles of martial arts, and parents should check within their communities for available resources. Equipment adaptations are not needed for this activity. Scuba and Snorkeling Freedom from gravity makes underwater adventure appealing to individuals with mobility impairments. Little adaptation to equipment is needed to allow older children and adolescents with disabilities to experience the underwater world. Lower-limb-deficient children may dive with specially designed prostheses or with adapted fins, or may choose to wear nothing on the residual limb. Similar to those with lower limb weakness or paralysis, they may use paddles or mitts on the hands to enhance efficiency of the arm stroke. Of particular importance is the maintenance of body temperature, especially in individuals with neurologic disability, such as spinal cord injury or CP. Wet or dry suits provide insulation for cool or cold water immersion. They also provide protection for insensate skin, which can be easily injured on nonslip pool surfaces, coral, and water entry surfaces. It is crucial that individuals receive proper instruction by certified dive instructors. Most reputable dive shops can provide information and referral. The HSA (www.hsascuba.com) is an excellent reference as well. Disabled divers are categorized based on the level of ability. They may be allowed to dive with a single buddy (as with AB divers), two buddies, or two buddies of whom one is trained in emergency rescue techniques. Although there is no particular exclusion from diving based solely on disability, a number of medical considerations may preclude scuba diving, including certain cardiac and pulmonary conditions, poorly controlled seizures, and use of some medications. Discussion with the primary care physician and with dive instructors should precede enrollment or financial investment. Scuba diving has also been used as adjunctive therapy in acute rehabilitation programs (87). Music Music has been used both as a therapeutic tool and as a means of artistic expression. Attentive behavior was increased in children with visual impairments who participated in a music program (88). There are many options for children who want to play music. Adaptations may be as simple as a universal cuff with a holder for drumsticks or as sophisticated as a computer program to put sounds together to form a musical piece. Two such computer programs are Fractunes and Switch Ensemble. Adaptive use musical instruments (AUMI) software allows the user to compose music with gestures and movements. Drumsticks can have built-up rubberized grips. Straps or a clamp may be used to hold a smaller drum onto a wheelchair for a marching band. Woodwind and brass instruments can be fitted with stands and finger pieces adapted for one-handed playing. Mouthpieces may have different angulations to allow easier access for those who have trouble holding the instrument. Some musical instrument makers, including Flutelab (www.flutelab.com), have become quite creative in how they can adapt their instruments. Other individuals have learned to play instruments such as the guitar with their feet (Figure 9.3).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree