12. Adaptive host response to infectious disease

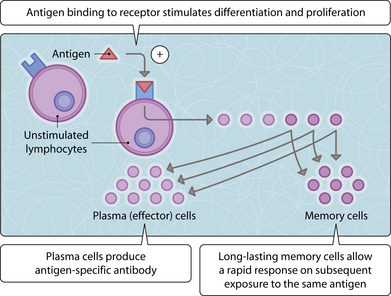

In contrast to innate immunity, acquired, adaptive or specific immunity is both highly specific in its recognition of foreign material and also becomes more efficient with repeated exposure to the same stimulus. The pivotal cell is the lymphocyte, which is able to respond to a single foreign antigen. This clearly requires a massive number of cells if an individual is to be able to react to the huge range of microorganisms that may be encountered in a lifetime. This diversity is generated by having multiple, variable germline genes coding for antigen receptors that recombine in a random manner within each precursor lymphocyte; these cells then mature in early life, by a process of positive and negative selection, to give a mixed population of competent cells that can be activated but which will not react against ‘self’. Upon exposure to the appropriate antigen, these cells proliferate and differentiate either into short-acting ‘effector’ cells or into long-lasting memory cells, which will allow a more rapid and greater response on subsequent exposure to the same antigen (Fig. 3.12.1).

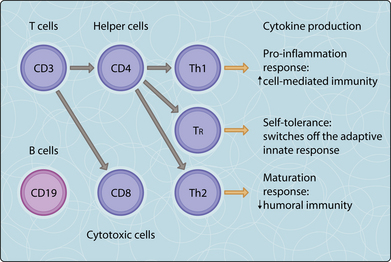

Lymphocytes may usefully be divided up into B lymphocytes (humoral immunity) and T lymphocytes (cell-mediated immunity) according to the molecules that they express on their surface, such as the cluster differentiation (CD) markers, and by their pattern of cytokine production. The T helper (Th) cells are subgroups of lymphocytes that are involved in activating and directing other immune cells (e.g. determining B cell antibody class switching, activation and growth of cytotoxic T cells). Mature Th cells express the surface protein CD4 and are known as CD4 T cells (Fig. 3.12.2).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>