Chapter 5 Acupuncture

Initial Examination

Initial Examination

Recreational Activities: Football referee

Musculoskeletal: Range of motion (ROM): unable to actively extend the elbow because of pain and swelling; passive stretching of the extensor muscle group, and elbow supination and pronation (with the forearm flexed to 90 degrees) all produce pain. Swollen around lateral complex of the elbow.

Neuromuscular: Force generation: unable to test right elbow extension, right wrist extension, or right grip strength because of aggravation of pain. Tests for left arm all scored 5/5 on manual muscle testing.1

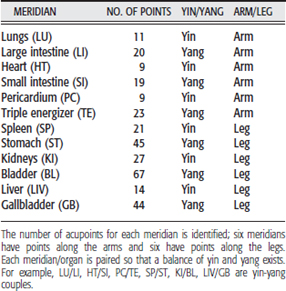

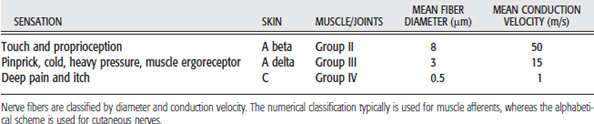

TCM Examination

TCM Examination

Listening: Normal level of speech

Presenting Tongue: Pale, damp with slight teeth marks

Fluid Intake: Drinks at least three to four cups of tea/coffee daily.

TCM Diagnosis and Plan of Care

TCM Diagnosis and Plan of Care

In this case study, internal organ problems and local channel problems appear to overlap.2 In TCM, local channel problems may be explained by invasion of a single or a combination of four external pathogenic factors (cold, heat, damp, or wind), which may lead to painful obstructive syndrome or Bi syndrome.3 In this case study, the symptoms of severe pain, which limits movement, and swelling could be explained by an invasion of cold and damp into the body.3 This invasion alters the balance of yin and yang, upsets the circulation of qi in the channel, and causes qi and blood to stagnate. Local stagnation of qi and blood along the LI meridian (Figure 5-1) of this client’s right forearm causes significant pain and swelling and lack of nourishment of the tendons and skin. This type of pain is improved by heat and aggravated by cold, which explains why the use of cryotherapy by the first physiotherapist was unhelpful.3 Another frequent cause of lateral elbow pain, according to Ji,4 is local trauma, which could be a likely explanation in this case study and would fit with a Western medical diagnosis of repetitive strain injury (RSI). Obviously in this case study this is linked to the client’s occupation as a bus driver.

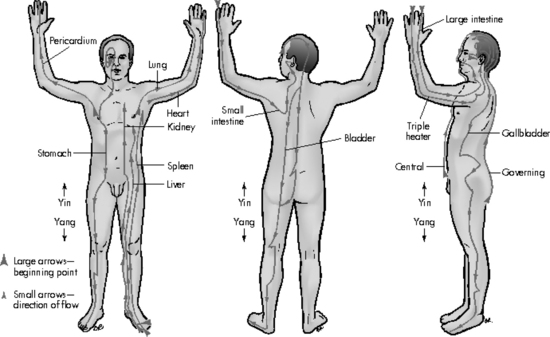

Figure 5-1 The 12 main meridians.

From Fritz S: Fundamentals of therapeutic massage, St Louis, 2004, Elsevier.

However, this client also is showing signs of disharmony in several organs, which suggests deficiency of his system and may explain why he was susceptible to an invasion of cold/damp. His reported symptoms of diarrhea/constipation reflect changes in large intestine function. directly linked to his local large intestine channel problem manifested in his elbow. This may be due to an underlying spleen qi deficiency, which causes collapse of the LI. The pattern of spleen qi deficiency is manifested by the symptoms of fatigue and chronic diarrhea and can be seen on his tongue (pale, damp, swollen, and tooth marked, which also may indicate yang deficiency of the kidney),5 his body type (overweight, especially the abdomen), and his pulse. He also is showing signs of liver disharmony in his pulses and reports of dizziness and temporal headaches along the GB line. His bowel symptoms, along with abdominal bloating and cramps and his reported intolerance to some foods, are suggestive of IBS. According to Gascoigne6 in TCM this corresponds to liver qi stagnation invading the spleen with an underlying kidney deficiency. Kidney deficiency in this case study is seen in the pulses, his sleep pattern, and tongue. A predominance of spleen qi deficiency explains the loose stools, and the abdominal distension and pain are caused by stagnation of liver qi.

Incorporating CAM into the Plan of Care

Incorporating CAM into the Plan of Care

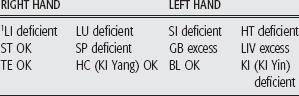

Using a TCM approach the plan of care is extended from one that treated the local problem (channel problem in TCM) to one that treats the organ disharmonies revealed by the detailed TCM diagnosis. Local channel problems will be treated in this case by use of a combination of local (LI 10, LI 11, LI 12) and distal points (LI 4, LI 5, TE 5). (See Table 5-1 for a list of the 12 main meridians and their corresponding organs.) Several organs show signs of disharmony and are treated accordingly. Use of large intestine points may help to resolve the large intestine organ problems (e.g., diarrhea and constipation).

This chapter describes the case of a 58-year-old male bus driver with lateral elbow pain, who is unable to work. The client is examined with use of a physical therapy and a traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) approach. The physical therapists, both trained as acupuncturists, consider including acupuncture, using a TCM approach in the plan of care. The decision is based on the physical therapists’ training, in the United Kingdom, where PTs can use acupuncture as an adjunctive analgesic modality after a conventional physiotherapy assessment or as part of treatment after a TCM diagnosis (see Appendix 1).

INVESTIGATING THE LITERATURE

The therapist uses two strategies to investigate the literature. The first is a detailed approach in which preliminary background reading is performed on the pathophysiology of pain and acupuncture therapy, including Eastern and Western perspectives on TCM. Next comes a search of databases and evaluation of the literature with use of reviews and primary sources. The second strategy is the use of the PICO format for a focused search to answer the clinical question generated by the case.

Preliminary Reading

A multitude of publications provide an introduction to acupuncture, many of which start with some form of historical perspective on acupuncture in East Asia,6,7 and how it was introduced to and embraced in the Western world.8 For example Pomeranz explains that although acupuncture was first brought to Europe in the seventeenth century, it only recently has been accepted widely because of the clash of Eastern and Western paradigms in health care.9 Briefly, acupuncture is a form of treatment derived from TCM, which is more than 2000 years old. Although the term TCM is used throughout this chapter, a great deal of heterogeneity exists in the practice of acupuncture in eastern Asia, and it is not a single, historically stable therapy. For example, whereas many Chinese practitioners insert needles deep into the tissues, Japanese practitioners use shallow needle and noninsertion needling techniques.10 Although the details of practice may vary, all traditional acupuncture is based on the Daoist concept of yin and yang10 (see Chapter 4).

To maintain health, yin and yang energies must be balanced; otherwise imbalance will result in disharmony/disease of the human body. This balance of yin and yang is controlled by a vital force or energy called qi (pronounced “chee”), which circulates between the organs along channels called meridians.10 The surface of the body has 12 regular meridians (Figure 5-1 and Table 5-1), and these correspond to 12 major functions or “organs” of the body. Although they have the same names (e.g., liver, kidney, heart), Chinese and Western concepts of the organs correlate only very loosely. Qi must flow in the correct strength and quality (and direction) through these meridians, which connect to interior organs, for health to be maintained.10 To stimulate healing and alter the energetic flow of qi and thus maintain the balance of yin and yang, acupuncture needles are applied at external points along the meridians. Each acupuncture point is considered to have a defined therapeutic action (some of which have been confirmed by MRI studies11), and thus particular defined points are chosen to treat a specific condition. Pain along a meridian could indicate a dysfunction of that meridian only or could reflect a dysfunction of the corresponding organ.7 In this particular case history, Richard appears to have a dysfunction of the meridian and corresponding organ.

When acupuncture is practiced from a TCM perspective, the interpretation of how the body functions is different from Western medicine, and a complex examination of many systems is carried out to diagnose the location of an imbalance in energy (see Chapter 4).

Western Medical Acupuncture

Many of the health professionals such as physical therapists, medical doctors, and dentists who practice acupuncture have dispensed with these TCM concepts6 and practice “Western medical acupuncture.” In Western medical acupuncture the clinician diagnoses the client from an orthodox point of view and applies acupuncture, based on the published scientific evidence, as an adjunctive technique.12 Acupuncture points are seen to correspond to physiological and anatomical features such as peripheral nerves and muscular trigger points,10 and the aim of treatment is to reduce pain and/or deactivate trigger points. Now a large body of scientific evidence details the mechanisms of action of acupuncture, in particular acupuncture analgesia. Several sources can be found on this topic.13–16

A starting point is an understanding of pain control mechanisms. Additional references provide information on the neuroanatomy of the nociceptive system and neurophysiology of pain and its modulation.17–20 To minimize confusion in reading these texts remember that nerve fibers are classified by diameter and conduction velocity. The numerical classification typically is used for muscle afferents, whereas the alphabetical scheme is used for cutaneous nerves (Table 5-2).

Scientific research suggests that acupuncture needles activate sensory afferents (variously A delta/Group III, A beta/Group II, and C fiber/Group IV afferents), which send impulses to the spinal cord and activate three centers (spinal cord, midbrain, and hypothalamus-pituitary) to cause analgesia through the release of endorphins and monoamines.16 Another suggestion is that activation of ergoreceptors in the muscle, which normally signal muscle load and are activated during voluntary muscle contraction, occurs by low-frequency ture. These receptors, which are served by group III muscle afferent fibers, are proposed to play a particularly important role in the production of AA.21

The main mechanisms of AA are outlined in the first three points below. The secondary mechanisms of AA are outlined in points four and five. Some of these are less well understood than others, and research to elucidate mechanisms is ongoing.

The choice of acupuncture points is important. Activation of acupuncture analgesia is believed to depend on several factors: the stimulation of the sensory afferents, the length of time the needles are retained, the location of the needles relative to the site of pain, and the intensity/method of stimulation.16 First, a dull ache, numbness, or heaviness indicates that the sensory afferents have been activated as a result of insertion and stimulation of the needle, and because maximum acupuncture analgesia occurs after 20 minutes of retention, needles should be retained for at least this time period.16,25

Second, needles can be stimulated in two ways: by hand, termed manual acupuncture, or by the use of electrical current at either low or high frequencies (EA). The majority of evidence on the mechanisms of AA is based on studies of EA in laboratory animals or transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) on the skin overlying acupuncture points, as opposed to manual acupuncture. The reason for this is that the stimulation parameters can be controlled carefully and precisely quantified with use of EA. The centers activated in AA (using EA) depend on the method and site of stimulation (i.e., within the segment of pain or extrasegmentally). Needles placed in the same segment as the pain can produce effects through all three principal mechanism described above, whereas needles placed distally produce analgesia via the hypothalamus and brainstem only. Local segmental needling therefore gives a more intensive analgesia than distal nonsegmental needling.16

Early experiments were seminal: they did establish that opioids were released in response to acupuncture needle insertion and stimulation. However, much debate still exists about the influence of parameter choice (for electrical stimulation) and the types of opioids released. Two main forms of EA have been explored: low-frequency, high-intensity needling, which activates all three principal mechanisms, and high-frequency, low-intensity needling, which activates the spinal cord and brainstem only.16 Low-frequency, high-intensity electrical stimulation produces pain relief through the release of beta-endorphin and enkephalins, whereas high-frequency currents produce analgesia via the opioid dynorphin.26,27 However, other parameter factors such as intensity and pulse duration may influence which opioid is released in the spinal cord.28 More research is required to explore these mechanisms in more detail.

Finally, the majority of scientific evidence for AA is based on EA in animals, and this has been extrapolated to provide evidence for AA in humans. However, other forms of evidence, such as laboratory studies and clinical studies in humans, which have explored the analgesic effects of EA and manual acupuncture, have shown conflicting results. Systematic review evidence for using EA in human laboratory studies (using acute pain models) suggests that a genuine analgesic effect exists; however, the evidence to date has not been able to show a similar clear effect for manual acupuncture.13 Moreover, although a systematic review of the effectiveness of acupuncture (EA and manual acupuncture) for chronic pain in clients demonstrated a clear analgesic effect compared with no treatment, inconsistent results have been reported compared with placebo, sham, or other treatments.29 Further research in humans therefore is required to establish definitively the mechanism for acupuncture-mediated analgesia.

Typical Acupuncture Treatment

The experience of the client during the first acupuncture treatment may differ depending on whether the clinician is using Western medical or TCM acupuncture. In the Western medical approach, acupuncture is used mainly as a pain-relieving modality after an orthodox diagnosis of the client. In contrast, a more complex whole system diagnosis takes place with TCM, and the explanations for effects given to the client may be different from those given by the Western acupuncture clinician. In Western acupuncture, points are chosen within the segment of pain and extrasegmentally: however, the choice of specific points for pain relief is not considered important. In TCM, acupuncture points may have multiple functions, as described for this case study in the section on plan of care and in Table 5-6 on p. 69, and may treat the local problem by moving stagnation of qi and blood (and thus reduce pain and swelling) and treat the organ disharmony.

Table 5-6 Location and Action of the Points Used for Elbow Pain

| ACUPUNCTURE POINTS | ANATOMICAL LOCATION | ACTION |

|---|---|---|

| LI 4 | On the dorsum of the hand between the first and second metacarpal bones, approximately in the middle of the second metacarpal on the radial side | Distal point for elbow pain |

| LI 5 | On the radial side of the wrist, in the anatomical snuff box between the tendons of extensor pollicis Longus and brevis | Distal point for elbow pain |

| LI 10 | 2 cun distal from LI 11 in a line between LI 11 and LI 5 | Local point for elbow pain |

| LI 11 | When the elbow is flexed in the depression at the lateral end of the transverse cubital crease, midway between LU 5 and the lateral epicondyle of the humerus | Local point for elbow pain |

| LI 12 | When the elbow is flexed, 1 cun above LI 11, in a line between LI 11 and LI 15 | Local point for elbow pain |

| LU 5 | In the depression on the radial side of the tendon of biceps in the cubital crease | To resolve swelling and pain in elbow |

| TE 5 | 2 cun proximal to the dorsal crease of the wrist, on the line connecting TE 4 and the tip of the olecranon, between the radius and the ulna | Distal point for elbow pain |

| Ashi | Any tender point | Local points for elbow pain |

| ORGAN DISHARMONY | ||

| SP 6 | Meeting point of three yin meridians of the leg, 3 cun above the tip of the medial condyle of the ankle, behind the fibula | Strengthens spleen, resolves damp, promotes liver function and smooth flow of liver qi, tonifies the kidneys, nourishes blood and yin, benefits urination, stops pain, moves blood, and eliminates stasis |

| ST 36 | 3 cun below ST 35 | Tonifies qi and blood, regulates the intestines, expels wind and damp, benefits stomach and spleen |

| LIV 3 | 1 cun in a dip between the fourth and fifth metatarsals of the foot | Promotes smooth flow of qi, calms abdominal pain, moves local stagnation of qi and blood |

| KI 3 | Level with the tip of medial condyle of the ankle in a depression between the condyle and the Achilles tendon | Tonifies the kidneys in any deficiency Pattern |

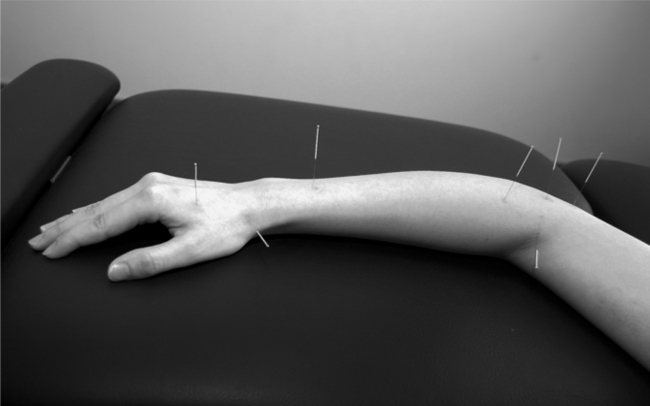

Regardless of the approach, a combination of points is used and a typical treatment entails the insertion of 3 to 15 needles, which are left in place for up to 30 minutes (Figure 5-2). Usually clinicians activate the needles to produce needle sensation or de qi because this is considered important from a Western and an Eastern perspective. De qi refers to a deep ache, a numbness, or a distending feeling around the point where the needle is inserted. Western medical acupuncturists interpret this as the activation of sensory afferents, which will produce AA, whereas TCM clinicians consider that the “arrival of de qi at each point” is important because it will help to open the channel, move qi, and rebalance the body’s energies.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Plan of Care

Plan of Care Reevaluation

Reevaluation Incorporating CAM into the Plan of Care

Incorporating CAM into the Plan of Care