INTRODUCTION

Fractures of the acetabulum are relatively uncommon injuries, usually resulting from high-energy trauma in young adult patients. Open anatomic reduction with internal fixation is the recommended treatment for fractures causing instability or incongruity of the hip joint. These fractures, which are often comminuted, are ideally treated by experienced fracture surgeons at institutions proficient in the care of multiply injured patients. Despite the best of care, however, these patients often have a protracted recovery and infrequently regain their preinjury level of physical capability (

1).

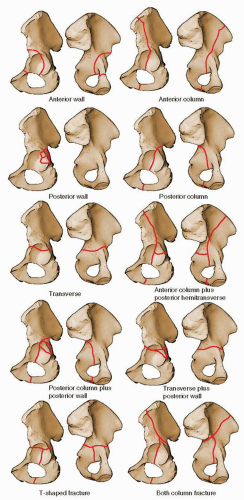

These fractures constitute an anatomically diverse group of injuries. Judet, Judet, and Letournel (

2) proposed the first systematic classification of acetabular fractures in 1961, which was based on the anatomic pattern of the fracture, and over time, this classification was modified and improved by Letournel. The comprehensive fracture classification systems of the Orthopaedic Trauma Association and the AO Foundation describe the alphanumeric coding of this “Letournel” classification and offer no clinical advantage. Therefore, the Letournel acetabular fracture classification continues to remain the international language of the majority of surgeons treating these complex injuries. This classification has 10 distinct categories, which are divided into five elementary types and five associated types (

Fig. 41.1;

Table 41.1).

The Kocher-Langenbeck, along with the extended iliofemoral and ilioinguinal, constitute the recommended “standard” approaches for the surgical treatment of acetabular fractures (

2). Despite the advent of many alternatives, the Kocher-Langenbeck approach remains a mainstay in this regard (

1).

INDICATIONS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS

As noted above, displaced fractures of the acetabulum resulting in joint incongruity or instability are best treated by open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF). Contraindications to surgery are ill-defined and not absolute. Important concerns include preexisting patient factors, such as poor general medical status and osteopenia, and factors that relate to overall patient prognosis, such as advanced age and associated injuries. All of these conditions must be considered with the knowledge that with nonoperative treatment in the face of joint incongruity or instability or both, the prognosis for hip-joint function is poor.

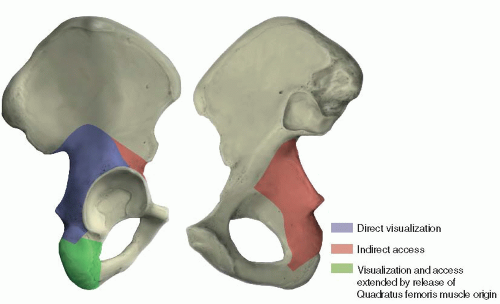

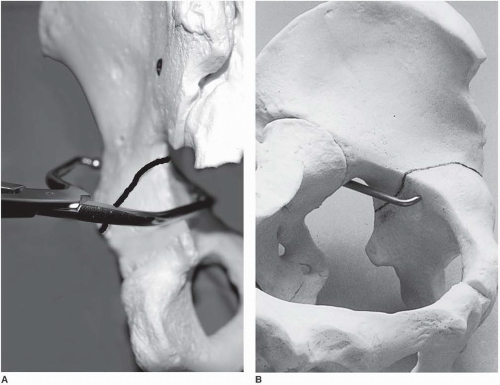

In choosing the appropriate surgical approach, the surgeon has an objective to select the least extensive exposure that allows sufficient bony access for anatomic joint reconstruction. The Kocher-Langenbeck approach provides direct visualization of the entire lateral aspect of the posterior column of the acetabulum (

Fig. 41.2) (

2). Indirect access to the true pelvis and to the anterior column can be attained by the palpating finger or through the use of special instruments (

Figs. 41.2,

41.3 and

41.4) (

2). Therefore, the Kocher-Langenbeck approach is applied in the treatment of fractures with the main displacement involving the posterior column. In the classification of Letournel (

Table 41.1), this group consists of six fracture types: posterior wall, posterior column, posterior column plus wall, transverse, transverse plus posterior wall, and T-shaped. The Kocher-Langenbeck approach is the surgical exposure of choice for the first three types, in which the fracture extent is limited to the posterior wall or column or both. For the transverse, transverse plus posterior wall, and T-shaped fractures, some decision making is required. All three of these fracture types have a transverse fracture line as a common component. As a general guideline, if the fracture is <15 days old and the transverse component is located at (juxta-) or below (infra-) the level of the roof (tectum) of the acetabulum (therefore not involving the weight-bearing area of the acetabulum), the Kocher-Langenbeck approach is indicated (

2). Otherwise, an alternative exposure, such as the extended iliofemoral approach, should be used. For acute juxtatectal- and infratectal-level transverse and T-shaped fractures, in which the major displacement occurs anteriorly at the pelvic brim and only minor posterior displacement, the ilioinguinal approach is perhaps the best choice.

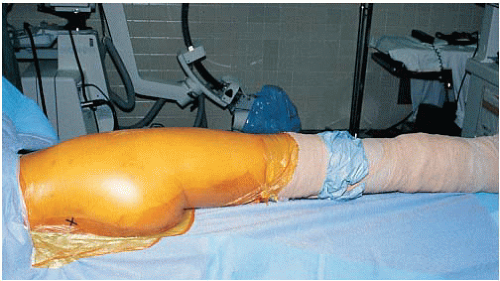

The status of the local soft tissues is an important additional consideration. Acetabular fracture surgery through a compromised soft-tissue envelope is ill-advised because of the increased risk of infection. Open wounds usually require débridement followed by delayed wound closure. Closed degloving soft-tissue injuries over the trochanteric region associated with underlying hematoma formation and fat necrosis (the Morel-Lavallee lesion) may be initially recognized by a fluid wave on palpation or may be later identified by the presence of a fluctuant, circumscribed area of cutaneous anesthesia, and ecchymosis. These injuries, even when closed, can be associated with the presence of pathogenic bacteria. Therefore, débridement followed by delayed wound closure and, subsequently, delayed fracture fixation may be required (

2). This delay, as noted previously, may

preclude use of the Kocher-Langenbeck approach. More recently, a percutaneous method has been reported in a small number of patients, using a plastic brush to débride the injured fatty tissue, which is then washed from the wound with pulsed lavage (

3). A medium closed-suction drain is placed within the lesion and removed when drainage is <30 mL over 24 hours. Fracture fixation is deferred until at least 24 hours after drain removal.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

In most cases, patients with an acetabulum fracture have sustained high-energy trauma. Therefore, examination of the injured limb, even in those with an apparent isolated injury, should be just one part of a comprehensive and systematic approach. Associated injuries can be life or limb threatening. The Advanced Trauma Life Support evaluation sequence should be followed (

4). As previously noted, soft-tissue injury has important implications regarding subsequent surgery; therefore, the soft tissues should be evaluated carefully. The incidence of preoperative, posttraumatic, sciatic nerve injury was reported as being as high as 31% (

5). Other peripheral nerves, such as the femoral and obturator nerves, also may be injured (

6). A complete and clearly documented neurologic examination is extremely important both for patient prognosis and for medical-legal concerns. Preoperatively, this evaluation should be repeated periodically.

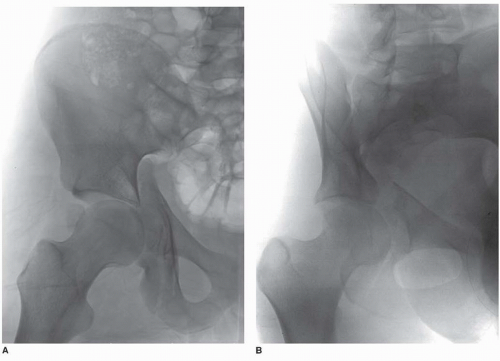

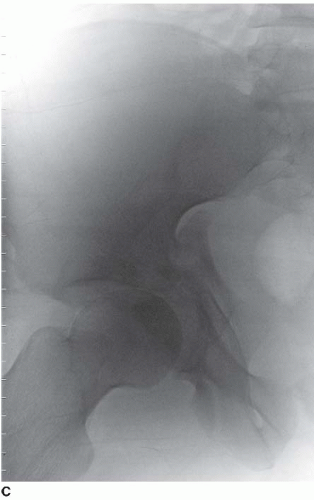

The initial anteroposterior (AP) x-ray of the pelvis can provide substantial diagnostic information regarding fracture type as well as indicate a need for emergency treatment (

Fig. 41.5). This x-ray must be supplemented by further studies to define completely the acetabular fracture pattern. The three necessary additional plain x-rays (

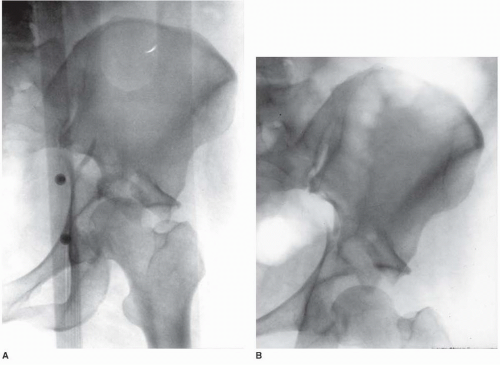

Fig. 41.6) are centered on the affected hip and include an AP and two 45-degree oblique views (the internal or obturator oblique view and the external or iliac oblique view) (

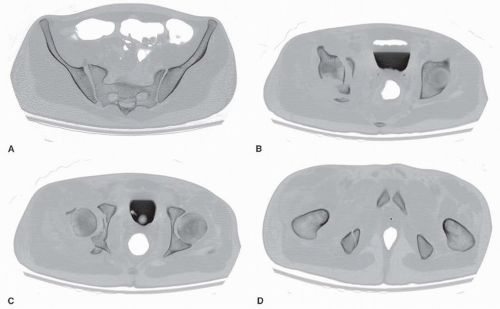

2). Although these four plain x-rays usually provide all the information needed to define the acetabular fracture type, the standard two-dimensional computed tomography (CT) scan can supply important additional information and is indispensable for preoperative

planning (

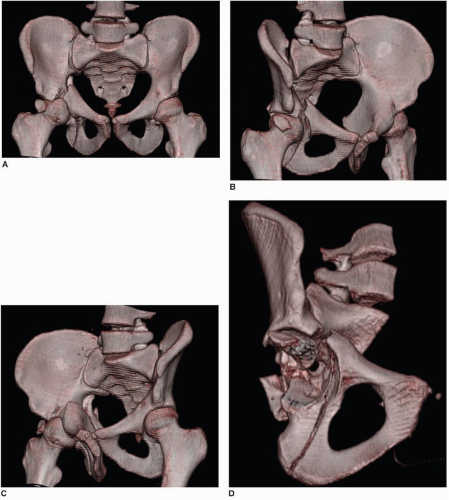

Fig. 41.7). The eventual universal availability of high-quality three-dimensional CT reconstructions may eliminate much of the mystery associated with the radiographic interpretation of acetabulum fractures (

Fig. 41.8). However, except for the AP hip x-ray, which in most cases provides the same information as the AP pelvis examination, the plain and two-dimensional CT radiographic studies continue to be indispensable and should be viewed concurrently to make the definitive fracture diagnosis (

2).

After careful physical examination and radiographic study, the appropriate surgical approach can be determined. The indications for emergency fracture fixation are uncommon (

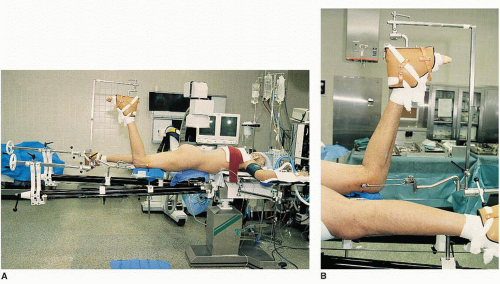

Table 41.2). Operative treatment is generally delayed 3 to 5 days to allow stabilization of the patient’s general status and for preoperative planning. My preference is to use preoperative, skeletal, femoral-pin traction both to maintain an unstable hip in a located position and to prevent further femoral head articular-surface damage from abrasion by the raw acetabular bony fracture surfaces (

Fig. 41.9). Significant intraoperative blood loss can occur. Approximately 2 units of blood should be made available, depending on the extent of the fracture pattern. The use of an autologous blood transfusion system may decrease the need for intraoperative, homologous, banked-blood transfusion.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access