Abstract

Objective

To investigate semantic memory in brain-injured patients.

Methods

We used the new word questionnaire (QMN) to assess the ability of 12 brain-injured patients and 12 healthy controls to define French words, which had been admitted to the dictionary in 1996 to 1997 or in 2006 to 2007.

Results

Despite amnesia or severe executive disorders, the brain-injured patients were able to learn new words and remember those that they already learnt. They successfully selected the relevant phrase in which the new word was placed and were reasonably good at recognizing the right definition from among decoys. In contrast, they had trouble defining the words and compensated for this by giving examples. These problems were correlated with their vocabulary and executive function scores in a battery of neuropsychological tests.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that frontal injury leads to an impairment in accurate word selection and the scheduling abilities required to generate word definitions.

Résumé

Objectif

Nous évaluons la capacité à définir des mots entrés dans le dictionnaire en 1996 à 1997 et en 2006 à 2007.

Matériel et méthodes

Nous utilisons les épreuves du questionnaire des mots nouveaux (QMN) chez 12 patients cérébrolésés et 12 témoins.

Résultats

Les patients apprennent de nouveaux mots (et conservent des anciens) malgré une amnésie ou un trouble dysexécutif sévère. Ils réussissent à choisir la phrase dans laquelle le mot s’intègre et assez bien leur définition parmi des leurres. Ils ont, en revanche, des difficultés à définir les mots et compensent par des exemples. Ces difficultés sont corrélées aux scores de vocabulaire et de tests sensibles aux fonctions exécutives.

Conclusion

Ces résultats suggèrent leur lien avec une atteinte frontale entravant la recherche de mots précis, ainsi que la planification d’une définition.

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

The creation of new words occurs through derivation, composition, abbreviation, borrowing or mutation of the meaning of an existing word; for example, a “mouse” is both a small rodent and a computer input device . A distinction is drawn between new forms or new meanings, which can be deduced (“DVD-ROM”, for example) on one hand and new words whose meaning can be deduced by use of the elementary mechanisms of language (notably on the morphological level, such as “ inexcitable” or “unexcitable”) on the other. The fields from which new words come also differ as the years go by. For example, the lexicon of horses and carriages was extremely present in the 19th century but gave way in the early 20th century to the lexicon of the automobile, which has itself since been modernized. At present, many fields are very fertile in this respect:

- •

computing and information technology;

- •

the media;

- •

the family;

- •

education;

- •

the environment.

In France, a word’s admission to the dictionary is subject to criteria set by the Académie française : the word must be well anchored in usage, used in spoken language, have a utility and comply with the spirit of the French language . The same applies to admission of foreign (and notably English) words to the dictionary: this process is subject to approval by ministerial terminology commissions. If a French equivalent does not exist, the word may undergo a morphological transformation and gallicization by keeping its root and gaining a French affix (e.g., “ kitchenette ”). However, the original form is sometimes maintained (e.g., “tuning”, “tofu”).

Memory, processing speed and attentional disorders are amongst the most commonly reported cognitive sequelae of head injury or stroke . It is routine practice to screen for cognitive and behavioural dysexecutive syndromes in brain-injured (BI) subjects, although it must be borne in mind that certain subjects may have problems in just one of these two domains . Concerning memory, patients may score very badly in tests of explicit memory (which require the conscious recall or recognition of information) whilst maintaining normal performance levels in various tests of implicit memory . Likewise, these patients can acquire new semantic knowledge relatively normally, including computer-related vocabulary , vocabulary from a foreign language , new concepts and novel information related to words having appeared after the onset of amnesia ; this occurs despite major recall problems (notably concerning the context of the learnt words). The nature of this knowledge acquisition is subject to debate in the literature. Authors such as Tulving et al. suggest that learning is more laborious for amnesic patients because they only use their semantic memory – in contrast to normal subjects, who also use episodic memory. In addition to the fundamental debate on whether amnesiacs can learn, it is essential to evaluate a subject’s abilities and have appropriate tools for doing so – especially when initiating specific rehabilitation with the goal of developing new tools and strategies.

The few literature studies to have addressed this crucial problem have not used standardized questionnaires or appropriate designs for probing correlations between learning quality and neuropsychological performance levels (notably episodic memory and executive function). We had an opportunity to select BI subjects with severe sequelae being monitored in a neuropsychological rehabilitation and social support centre and to measure their ability to learn words having recently entered the French language.

1.2

Population and methods

1.2.1

Population

Twelve patients participated in this study in 2008 (seven women and five men; mean age: 34 years; lowest age: 23 years). Seven had suffered from head trauma and five had suffered from a stroke at some time between 1997 and 2006. To simplify matters, we shall refer to the these study subjects collectively as “BI patients”. The mean time since injury was four years and seven months. Subjects presenting major language disorders or an excessively low socioeducational level were not included in the study.

The control group was composed of 12 subjects matched for age, educational level and gender.

1.2.2

The new word questionnaire (QMN)

This questionnaire deals with newly coined French words admitted to the dictionary between 1996 and 1997 and between 2006 and 2007. It features 22 items divided into two groups (11 for each period). We chose these two periods in order to compare words learnt 10 years apart, since the least recent would have been consolidated for longer. The words were selected from the Larousse dictionary, since the publishers had kindly informed us that the word selection criteria had not changed over this period. Given that the words had appeared recently, it was not possible to select them according to their measured frequency; the last test of this kind dates back to 1971 (the BRULEX database created by a Belgian group on the basis of the French language treasury). We systematically paired a word from 1996 to 1997 with one from 2006 to 2007, in terms of its shape or meaning. Hence, there were semantic pairings and superficial pairings ( Table 1 ). Other criteria were also applied. We included foreign words (particularly English ones: “bimbo”, “blog” and “tofu”) in each list, in order to reflect changes in the French language as closely as possible. It is noteworthy that 7 and 19.5% of the new words admitted to the Larousse dictionary for the periods 1996 to 1997 and 2006 to 2007, respectively, were derived from English – justifying the higher proportion in our second list. The words concerned a variety of fields, including:

- •

computing and information technology;

- •

the media;

- •

health;

- •

the domestic sphere;

- •

food;

- •

leisure activity.

| Words from 1996–1997 | Words from 2006–2007 |

|---|---|

| Semantic pairing | |

| Internaute | Blog |

| Tofu | Oméga 3 |

| Aquagym | Accrobranche |

| Meuf | Bimbo |

| Karaoké | Car-jacking |

| Surpoids | Anti-âge |

| Shape pairing | |

| Microtrottoir | Coming-out |

| Canyoning | Tuning |

| DRH | TOC |

| 3 D | USB |

| Lingette | Dosette |

The QMN comprises three tasks: a free recall task, a multiple-choice questionnaire (MCQ) for word definitions and a choice of two contextual situations for each word ( Fig. 1 ). The participant is first asked to define the word as precisely as possible. He/she must then say which of three given definitions is most appropriate. In the most cases, the two incorrect definitions were morphologically similar: “bimbo” can be confused with the elephant “Dumbo”, “coming-out” can be confused with “come-back” and (car) “tuning” can be confused with a (radio) “tuner”. We simplified the definitions as much as possible, in order to adapt the task to suit the patients. For example, the definition of “tofu” was changed from “a Japanese dish based on soybean curds” to “a Japanese food”. Lastly, the context task required the participants to choose between two phrases, of which only one used the word correctly. The incorrect phrase was unrelated to the previously given definitions. In these tasks, the words from 1996 to 1997 were always presented before those from 2006 to 2007. For all the three tasks, the verbal presentation was reinforced by a written presentation, in order to increase the likelihood of word recognition. For the recall task, a lack of response was allowed but the subject was then asked whether he/she had already heard the work and, if so, in which field. Recall was scored as 0 (incorrect answer or no answer), 0.5 (a vague definition – in the right semantic field but lacking the main characteristics) or 1 (complete definition of the word and its main properties). In order to allow additional qualitative analyses, answers were then classified into three categories: definition through an example (“it’s like…”), by a use (“it’s for…”) or as a true conceptual definition. For the MCQ involving definitions and contexts, an answer was obligatory and was scored as 1 when correct and 0 when incorrect. During the QMN’s development phase, the questionnaire had been tested on 72 normal subjects (equal numbers of men and women, aged between 20 and 79 years) divided into two groups according to their educational level. We also have data for other patient groups.

1.2.3

Neuropsychological assessment

All BI subjects underwent a comprehensive assessment of global neuropsychological status, memory, executive function and language. The test battery included the Mini Mental Test Examination (MMSE), the 16-item Free and cued selective reminding test (FCSRT) , the Wechsler adult intelligence scale (WAIS) digit symbol subtest , the Trail making test (TMT) form A and form B, the Stroop test , the WAIS vocabulary subtest , the two-minute verbal fluency (category animal and letter “p”) and the DO80 picture naming task .

1.3

Statistical analysis

The correct answer rates were arc sine transformed to enable us to perform an analysis of variance (ANOVA) on the gathered data. Additional analyses (Student’s t test and a contrast analysis) were used to evaluate inter- and intragroup effects. In this study, we examined three independent variables: “group”, “period” and “subtest”.

1.4

Results

1.4.1

Comparative analyses of the subjects’ performance levels

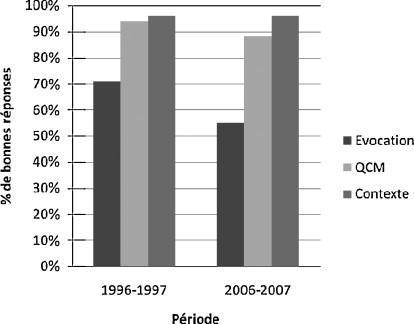

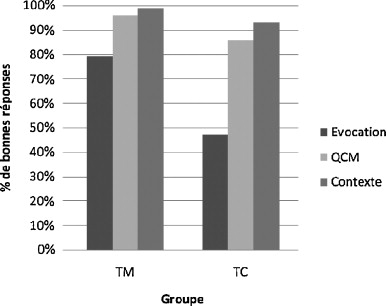

A (“group”) 2 × (“subtest”) 3 × (“period”) 2 repeated-measures ANOVA for the latter two factors was performed on the percentage of correct answers. It revealed an effect of “group” ( F [1,22] = 15.88; P = 0.0006), which can be explained by a lower percentage of correct answers for the patients (75%) than for the control subjects (91%). The period in which the word was admitted to the dictionary also influenced the success rate ( F [1,22] = 22.96; P = 0.0001), since words admitted in 1996 to 1997 prompted a higher success rate (86%) than those admitted in 2006 to 2007 (80%). However, the observed “period” × “subtest” interaction ( F [2,44] = 21.00; P = 0.0001) shows that the effect of “period” is mainly explained by performance in the recall subtask ( F [1,44] = 74.62; P = 0.0001) and the MCQ ( F [1,44] = 8.20; P = 0.0064), whereas “period” did not have any influence on the context task ( F [1,44] < 1). ( Fig. 2 ). In contrast, “period” did not interact with “group”, since both patients and controls were found to be sensitive to the words’ degree of novelty in both the recall task and the MCQ. This analysis also showed an effect of the “subtest” factor ( F [2,44] = 155, 75; P = 0.0001), since the success rate was higher in the context task (96%) than in the MCQ (91%) ( F [2,44] = 5.88; P = 0.0195) which, in turn, yielded better results than the recall task (63%) ( F [2,44] = 5.88; P = 0.0195). In contrast to “period”, the nature of the subtest interacted with “group” ( F [2,44] = 23.89; P = 0.0001). As shown in Fig. 3 , the patients performed less well than control subjects, especially in the recall task – the most difficult subtest ( t [22] = 5; P = 0.0001). This impairment was also significant (although to a lesser extent) for the MCQ ( t [22] = 2.49; P = 0.02) and the context task ( t [22] = 2.29; P = 0.03). We calculated the intergroup differences in success rate for each task, in order to compare the sizes of the respective impairments. This analysis confirmed that the patients’ poor performance was more marked in the recall task than in the MCQ ( t [22] = 8.12; P = 0.0009) and in the context task ( t [22] = 7.13; P = 0.0002), whereas the latter two subtests did not significantly distinguish between the patients’ deficits.

1.4.2

Qualitative analysis

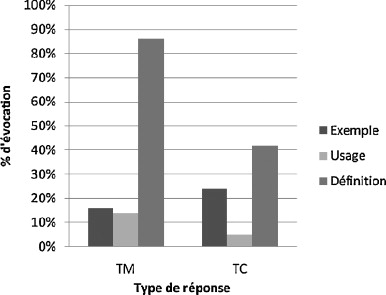

The subjects’ answers in the recall task were analysed qualitatively. In this subtest, most of the participants did not restrict themselves to providing a strictly conceptual definition of the word but also cited examples or defined the word in terms of use. Based on this observation, we distinguished between three categories of information. We adopted a binary scoring system; for each defined word, a score of 0 or 1 was attributed to each category of information (use, example and definition). A percentage recall rate could thus be calculated for each type of answer. These parameters were independent and thus we performed an ANOVA with the answer category (use, example, definition) and period (1996–1997, 2006–2007) as intraindividual factors and the group (patients, controls) as the interindividual factor.

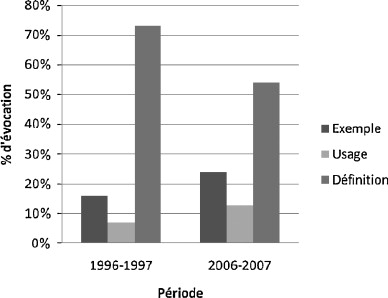

This analysis revealed that the patients gave significantly less information in general than the control subjects ( F [1,22] = 37.18; P = 0.0001). It also showed a main effect of answer type ( F [2,44] = 160.82; P = 0.0001), which interacted with the period, ( F [2,44] = 36.46; P = 0.0001). As shown in Fig. 4 , the words admitted in 2006 to 2007 were more likely to be associated with definitions citing examples ( F [1,44] = 37.18; P = 0.0001) or uses ( F [1, 44] = 5.84; P = 0.0199) than words having entered the dictionary 10 years previously but were less often associated with conceptual definitions ( F [1,44] = 11.95; P = 0.0012). Lastly, the effect of the answer type also varied according to the group ( F [2,44] = 35.15; P = 0.0001; see Fig. 5 ). The percentage recall rate associated with correct conceptual definition was lower for patients than for controls ( t [22] = 8.32; P < 0.0001). The same was true of use recall ( t [22] = 3.94; P < 0.0005). In contrast, the percentage of words associated with an example was higher in the patient group than in the control group ( t [22] = −2.12; P < 0.0265). We did not observe an answer type × period × group interaction ( F [2,44] < 1).

1.4.3

Correlation analysis

We looked for correlations between the various neuropsychological task scores and the QMN (its overall score, the scores for each period of word introduction and the subtest scores). Only three neuropsychological tasks correlated with the QMN: the 16-item free recall/cued recall task, the WAIS vocabulary test and the letter fluency test.

Firstly, we found a positive correlation between performance in the 16-item free recall/cued recall task score and the overall QMN score ( R = 0.68; P = 0.015). This relationship also held true for each QMN subtest: the recall ( R = 0.63; P = 0.028), MCQ ( R = 0.69; P = 0.013) and context tasks ( R = 0.68; P = 0.015). If only words admitted to the dictionary in 1996 to 1997 were taken into consideration, recall of the 16 items in the free recall/cued recall test correlated with the overall QMN score ( R = 0.78; P = 0.003) and all subtests ( R = 0.74; P = 0.005 for recall; R = 0.80; P = 0.002 for the MCQ; R = 0.63; P = 0.027 for the context test). In contrast, for words admitted to the dictionary in 2006 to 2007, only the context subtest correlated with the recall score for the 16 items in the free recall/cued recall test ( R = 0.66; P = 0.019).

Furthermore, the total score obtained for words from 2006 to 2007 (but not that for words from 1996 to 1997) was positively correlated with the letter fluency score ( R = 0.60; P = 0.039 and R = 0.78; P = 0.003, respectively) and the vocabulary score ( R = 0.59; P = 0.045; R = 0.68; P = 0.015), and this was true for all three subtests.

1.5

Discussion

This study focused on how words newly introduced into the French language are learned. It was performed on a small number of subjects, which means that caution must be used when interpreting the results. Furthermore, it concerned subjects who were BI as a result of a head injury or stroke. The question of whether it is appropriate to pool subjects with different clinical profiles and potentially seen at different stages in disease progression or recovery must be raised. Patient selection was guided by the fact that common cognitive impairments in daily life had prompted (at a particular point in time in their care schedule) admission to a specialist neuropsychological rehabilitation centre. The latter focused its efforts on improvements in daily life . In previous work in our department, a comprehensive neuropsychological assessment of the patients and their behaviour during rehabilitation had not distinguished between the aetiological natures of the patients’ impairments . The small sample size prevented us from performing rigorous intersubject comparisons. None of the subjects with vascular lesions presented aphasia. The stroke injuries consisted of rupture of an aneurysm or right-side hemispherical angioma in three cases, an intracerebral haemorrhage following surgery to remove a ventricular tumour and the sequelae of a left-side parietal stroke.

The QMN test is designed to evaluate knowledge of (and ability to define) words that have recently been admitted to the dictionary and the everyday use of which is recent. By virtue of a presentation described as “fun” and “pleasant” by the 12 adult BI or stroke patients and 12 control subjects, this test provided insight in the way that these words are understood and that their meaning is retrieved.

The QMN consisted of a list of words which the subjects knew well enough to score almost perfectly in the context task (with success rates of 99.30% for the controls and 93.20% for the patients). Even though the words arose recently, they were familiar enough for the subject to designate the correct context-phrase from a decoy. Previous work performed in healthy adults divided into six age classes (ranging from 20 to 79 years of age) had shown that the context task was both the highest-scoring test and the only one found not to depend on the subject’s age . Here, we show that only context task performance is correlated with the recall score of the 16-item test free recall/cued recall test (for both the words from 1996 to 1997 and those from 2006 to 2007); this suggests that performance is more strongly founded on overall recognition ability than an aptitude to retrieve information in the memory without a precise cue.

Choice of the correct definition of the word in the MCQ test and (to an even greater extent) elaboration of a conceptual definition posed more problems for all participants in the study – especially for the most recent words. This finding confirms the results observed in healthy subjects aged between 20 and 79 years in previous research work . In contrast to the context task, both the MCQ task and the recall task were sensitive to the period of dictionary entry; more recent words yielded lower performance levels than those admitted longer ago. For the study population as a whole (i.e., patients and controls), the difficulty of the task (particularly for recall, which required the construction of a true definition and involved abstraction) is not the only explanation for the drop in performance levels. The significant novelty of the words also contributes – even when the subjects are already familiar enough with the word to successfully judge the relevance of the latter’s use in a phrase.

The effect of brain lesions in the BI or stroke patient is evidenced by poor performance, compared with controls. However, these difficulties are not expressed homogeneously. The “group” factor interacts with the “subtest” factor but not with the period in which the word entered the dictionary. In terms of overall performance in the QMN test, the patients were not disproportionately handicapped by having learnt the words shortly before their injury or, indeed, afterwards (i.e., for words admitted in 2006 to 2007). The injury had a negative influence on performance, which depended more on what had to be done to show that a word had been understood than the word’s novelty per se . In fact, the drop in performance levels was less marked when the subject had merely to indicate knowledge of the appropriate usage of the word (in the context task) or choose the best definition from amongst those suggested (the MCQ) than when the same subject was asked to construct and formulate a definition or explain verbally a coherent situation for the word (the recall task). The patients’ success in the context task shows that even in amnesia, access to knowledge remains possible and is favoured by provision of contextual situations (even virtual ones) as examples. Acquisition of new knowledge (i.e., the words from 2006 to 2007) appears to be possible; despite being significantly lower than for controls, the patients’ overall performance was very good (a correct response rate of 80% versus 86% for controls). The ability to acquire new knowledge in severe amnesia has already been reported (19, 23, 24) and is also illustrated by the ability to acquire semantic knowledge (notably educational knowledge) in children who do not even have any episodic memory of this learning (due to hippocampal damage at birth) . Indeed, we have described a female patient presenting a severe memory impairment but who was capable of voluntary activity by using information technology tools (management of a photo library) after intensive training but more than 10 years after her head injury, in the absence of episodic memories of learning and with long-term acquisition of the new procedural skills .

The extent of the BI patients’ failure in the recall task typifies the latter’s difficulties relative to the subjects with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or Alzheimer’s disease (AM) tested in a previous study: the latter stood out from controls in terms of the size of the drop in performance level in an MCQ – a task in which BI patients do rather well . By revealing the particularly poor performance of BI patients in the recall task, the QMN test replicates a disorder that has already been observed in this patient group . The test emphasized the patients’ difficulty in producing a definition unprompted, despite the fact that they are subsequently capable of recognizing the most relevant of three definitions. On one hand, this impairment may well be explained by damage to the frontal and prefrontal regions and corresponding problems in organizing the retrieval of precise concepts and words in order to build an explanation. On the other hand, there are perturbations of the scheduling required to build a definition that has to comply with the implicit constraints associated with this task (i.e., not using words that belong to the same family as the word to be defined and ensuring that the suggestion contains elements required to resolve any ambiguities and thus enable true understanding by a third party) .

Our qualitative analysis of the answers in the recall task provides insight into the strategies used by the participants to compensate for their difficulty in defining the words conceptually. The type of answer provided by the subjects as a whole varied according to the word’s degree of novelty, since conceptual definitions were given less frequently for the most recent words than for those having been admitted to the dictionary 10 years earlier. Consequently, the production of definitions involving uses or examples was higher. The absence of an answer type × period × group interaction does not enable us to say that the patients stood out from the controls in terms of a change in the impact of significant word novelty on the response strategy. However, the interaction between answer type and group shows that for the set of words used in the test, the patients strongly restricted their conceptual definitions (relative to the controls). Hence, it is clearly the elaboration of definitions of this type that causes them problems (and not only for very recent words).

Whereas our analysis of the study population as a whole revealed a compensation for the negative effect of the significant word novelty on conceptual definitions by recalling a use or examples, the patients more specifically compensated for their difficulties in forming conceptual definitions by describing personal memories associated with these words, rather than by resorting to “functional” definitions. The percentage of words defined by a use was lower for patients than for controls. The difficulty in adopting this conceptual strategy has also been observed in MCI patients and (to an even greater extent) in patients suffering from early-stage AM . This finding can doubtless be explained by the particular vulnerability of semantic knowledge of the functional properties of objects. For example, the long-term follow-up of AM patients has shown earlier, more marked deterioration of their knowledge of the functional characteristics of animals than of the latter’s visual aspects .

Furthermore, the patients’ neuropsychological test results reveal a correlation between the processing of words from 2006 to 2007 and performance in the letter fluency and vocabulary tests. The WAIS vocabulary subtest reflects the overall quality of a subject’s vocabulary and represents one way of comparing the ability to retrieve new words relative to general vocabulary. It is difficult to more specifically evaluate previously known words via a methodology similar to that used here, in view of the subjects’ age range. The patients’ difficulties in defining the very new words are probably not unrelated to their difficulty in retrieving lexical knowledge and the drop in executive function (as reflected by the score in the letter fluency test) . Words admitted to the dictionary in 1996 to 1997 were more likely to have formed part of a patient’s lexicon before the accident or incident and so the representations of these words are doubtless more broadly and more stably integrated into their semantic networks; this facilitates automatic retrieval of the mentally associated vocabulary and makes it easier to find words to adequately build definitions or to remember a relevant personnel episode to illustrate an example.

On the whole, the QMN provides us with information on the quality and the accuracy of an individual’s knowledge of newly coined words. This tells us whether:

- •

the individual has a deep enough understanding;

- •

his/her abstraction capacity is good enough to provide a conceptual definition;

- •

he/she can easily evoke a context for usage of this term or link it to a relevant example (the recall task);

- •

a few cues have to be provided before the meaning of the word is recognized (the MCQ);

- •

a greater number of concrete, contextualized cues are required for this recognition (the context task).

The results for the control subjects confirmed previous reports on this test and notably reproduced the negative effect of significant word novelty on successful definition but not on the subject’s ability to rate the pertinence of word use in phrases. The data recorded with BI or stroke patients shows that these pathologies do not suppress the ability to recognize recently acquired words when material cues are provided. The test revealed that these patients have significant difficulties in elaborating conceptual definitions ; this is doubtless related to impaired executive function and can mask the preservation of a certain degree of word comprehension. This finding suggests that investigation of vocabulary or naming ability in this type of patient is not sufficient; it is advisable to explore other modes of knowledge retrieval in order to refine the diagnosis and envisage new rehabilitation approaches – notably when teaching new vocabulary to subjects.

2

Version française

2.1

Introduction

La création de mots nouveaux se fait par dérivation, composition, abréviation, emprunt ou par mutation des sens du mot existant ; par exemple, la souris, l’animal, est aussi la souris informatique . On distingue, d’une part, les formes nouvelles et les sens nouveaux, dont la signification ne peut être déduite (ex., DVD-ROM ) et, d’autre part, les mots nouveaux dont le sens peut être déduit par l’usage des mécanismes élémentaires de la langue, notamment au niveau morphologique (ex., inexcitable ). Les mots nouveaux relèvent de domaines qui évoluent. Le lexique du cheval et de l’attelage, très présent au 19 e siècle, a ainsi fait place au début du 20 e siècle au lexique des véhicules automobiles qui s’est lui-même modernisé. À notre époque, beaucoup de domaines sont à cet égard très féconds :

- •

l’informatique ;

- •

l’audiovisuel ;

- •

la famille ;

- •

l’éducation ;

- •

l’environnement.

Cependant, pour entrer dans le dictionnaire, un mot doit remplir des critères fixés par l’Académie française : il doit être bien ancré dans l’usage, utilisé dans le langage oral, présenter une utilité et être conforme à l’esprit de notre langue . Il en est de même pour l’entrée de mots étrangers, notamment anglais, dans le dictionnaire : celle-ci est soumise à des commissions ministérielles de terminologie (CMT). Quand l’équivalent français n’existe pas, le mot peut faire l’objet d’une transformation morphologique (il est « francisé ») en conservant sa racine et en ajoutant un affixe de la langue française (ex., kitchenette ), mais sa forme d’origine est parfois maintenue (ex., tuning, tofu ).

Parmi les symptômes les plus fréquemment rapportés au décours d’un traumatisme crânien (TC) ou d’un AVC entraînant des séquelles cognitives, figurent les troubles de la mémoire, l’attention ou la vitesse de traitement . On recherche volontiers cliniquement chez les sujets cérébrolésés dans les suites d’un TC ou d’un accident vasculaire cérébral (AVC) un syndrome dysexécutif cognitif et comportemental, sachant que certains sujets peuvent n’avoir des difficultés que sur un seul de ces axes . Concernant la mémoire, les patients peuvent obtenir des performances très faibles aux tests de mémoire explicite qui requièrent la récupération consciente d’une information en rappel ou en reconnaissance alors qu’ils conservent des performances normales à différents tests de mémoire implicite . De même, ils peuvent acquérir plus ou moins normalement de nouvelles connaissances sémantiques tels que des mots de vocabulaire liés à l’informatique , le vocabulaire d’une langue étrangère , de nouveaux concepts et de nouvelles informations relatives à des mots de vocabulaires apparus après l’installation de l’amnésie et ce en dépit de difficultés majeures de récupération notamment du contexte de ces apprentissages. La qualité de ces nouvelles connaissances acquises est discutée dans la littérature. Des auteurs comme Tulving et al. suggèrent que l’apprentissage est plus laborieux pour les patients amnésiques puisqu’ils n’utilisent plus que leur mémoire sémantique pour apprendre, à la différence des sujets normaux qui utilisent également leur mémoire épisodique. Hormis la question théorique de la capacité d’apprendre alors qu’on est amnésique, il reste fondamental d’évaluer les capacités des sujets et de disposer d’outils pour le faire, ce notamment lorsqu’on met en place des rééducations spécifiques ayant pour objectif de développer de nouveaux outils ou de nouvelles stratégies.

Les quelques travaux de la littérature qui ont souligné ce problème crucial ne proposent pas de questionnaire standardisé ni d’études de groupe recherchant des corrélations entre la qualité de l’apprentissage et le niveau de difficultés dans les tests neuropsychologiques évaluant notamment la mémoire épisodique et les fonctions exécutives. Nous avons eu l’opportunité de sélectionner des sujets cérébrolésés, ayant des séquelles sévères, suivis dans un centre d’accompagnement social et de rééducation neuropsychologique et de mesurer leur apprentissage de mots récents dans la langue et rapportons les données de cette étude.

2.2

Population et méthode

2.2.1

Population

Douze patients ont participé à cette étude en 2008 : sept femmes et cinq hommes, âgés en moyenne de 34 ans, le plus jeune ayant 23 ans. Sept d’entre eux ont eu un TC et cinq ont présenté un AVC, entre 1997 et 2006. Pour simplifier les choses, nous parlerons de patients TC. Le délai évolutif était en moyenne de quatre ans et sept mois. Les sujets présentant des troubles prédominants du langage ou un trop faible niveau socioéducatif, n’ont pas été recrutés pour cette étude.

Le groupe témoin (TM) est composé de 12 sujets appariés en fonction de l’âge, du niveau d’éducation et du sexe.

2.2.2

Le questionnaire des mots nouveaux (QMN)

Le questionnaire porte sur les nouveaux mots de la langue française apparus dans le dictionnaire entre 1996 et 1997, et entre 2006 et 2007. Il est composé de 22 items divisés en deux listes (11 mots pour chaque période). Nous avons retenu ces deux périodes, afin de comparer des mots qui ont été appris à dix ans environ d’intervalle, les moins récents pouvant avoir bénéficié d’une plus longue consolidation. Les mots ont été sélectionnés dans Le Larousse , sachant que le mode de sélection est resté le même pour ces deux décennies (renseignements fournis avec courtoisie par l’éditeur). Ces mots n’ont pas pu être sélectionnés en fonction de leur fréquence dans la mesure où ils sont trop récents pour avoir été soumis à ce genre de test, le dernier datant de 1971 (base de données BRULEX élaborée par une équipe de Belgique sur la base du Trésor de la langue française). Nous avons apparié systématiquement un mot de la période 1996 à 1997 à un mot de la période 2006 à 2007, avec comme critères la forme du mot (critère morphologique) ou son contenu (critère de sens). Il y a ainsi deux types d’appariements : sémantique et de surface ( Tableau 1 ). D’autres critères ont, par ailleurs, été retenus. Nous avons, ainsi, inséré dans chaque liste des mots d’origine étrangère, plus particulièrement anglo-saxonne, afin de refléter le plus possible l’évolution de la langue française ( bimbo , blog , tofu ). Il faut d’ailleurs souligner que si l’on observe les listes de nouveaux mots du dictionnaire Le Larousse pour les périodes de 1996 à 1997 et 2006 à 2007, le pourcentage de mots anglais est passé respectivement de 7 à 19,5 %, ce qui justifie leur plus grand nombre dans notre deuxième liste. Les mots concernent des domaines variés, notamment, ceux :

- •

de l’informatique ;

- •

des médias ;

- •

de la santé ;

- •

de la sphère domestique ;

- •

de l’alimentation ;

- •

des loisirs.