Rehabilitation management of children with cerebral palsy (CP) brings together parents and doctors. The primary goal of the contact is to improve the individual child’s potential and to improve the child’s functional outcomes. Frequently, parents are interested in not just their own child, but the population of children with cerebral palsy. Physicians can provide information for both purposes. Successful parent–professional relationships are rewarding and powerful. Combining the passion of the parent and the expertise of the physician can enhance collaboration for advocacy efforts that improve outcomes for children with cerebral palsy. An increasingly important component in the parent–medical collaboration is the identification of networks of local and national support for families of children with cerebral palsy. Fortunately, parents and organizations focused on children with cerebral palsy are seeing the necessity for collaboration to build community awareness, implement education programs, and spearhead pediatric cerebral palsy advocacy on a nationwide basis.

Rehabilitation management of children with cerebral palsy (CP) brings together parents and doctors. The primary goal of the contact is to improve the individual child’s potential and to improve the child’s functional outcomes. Frequently, parents are interested in not just their own child, but the population of children with CP. Physicians can provide information for both purposes. Successful parent–professional relationships are rewarding and powerful. Combining the passion of the parent and the expertise of the physician can enhance collaboration for advocacy efforts that improve outcomes for children with CP.

This article (1) reviews essential aspects of communication, (2) discusses the importance of parent networks, (3) encourages collaboration of physicians and parents as a force for advocacy, and (4) provides information on organizations that can help physicians develop the skills to be effective advocates.

Communication

The medical encounter consists of 2 experts: the parent and the physician. The parent knows more than anyone about the child and the family; the physician brings medical expertise and experience. The medical visit is based on communication between these 2 experts. Of all the skills of a physician, listening is the key to understanding the experience of the child and the parent.

Talk forms the basis of the encounter; however, the importance of talking is often underestimated. Most medical historians agree that talking has shifted away from the center of the encounter. Shorter identified the post–World War II era (coinciding with the development of antibiotics) as the time that the disease rather than the patient’s experience became the focus of the encounter. The practice of linear interviewing, with yes/no questions as the format of conversation, curtails the opportunity for support and discussion of social aspects of the condition. This is reflected in a study focusing on the first 90 seconds of the patient encounter, in which the patient’s response to the first question was completed only 23% of the time, and physicians interrupted the response after an average of 15 seconds.

A small observational study compared internal medicine physicians using electronic medical records with those using paper records. Although the study did not identify statistically significant differences, it suggested that physicians using electronic medical records were less likely than other physicians to attend to psychosocial issues and the patient’s experience of an illness.

In the conversation between the physician and the parent of a child with CP, providing appropriate care often depends on a shared perception of the problem that needs attention. A particular constraint of the electronic medical record may be a decreased opportunity to assess a parent’s perception of the evolving needs of a child with a chronic neurologic disorder such as CP.

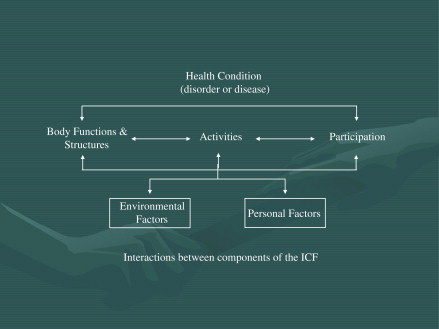

Rehabilitation management takes into account the model of outcome of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) ( Fig. 1 ). The continuum of body structures and function, activities, and participation creates opportunities to look beyond health status and assist with integration into the community. The patient encounter in rehabilitation includes all dimensions of the ICF model. The model encompasses the personal and external factors that affect the more traditional biomedical model of body structure/body functions, activities, and participation categories. Personal factors that affect outcome include access to information and networking support for parents and children. External factors include the societal barriers that may impede participation, such as health care disparity, educational barriers, and lack of adequate funding for research in CP at the national level. Communication that is free flowing is necessary to gather information that touches on all aspects of the ICF model. Nonlinear communication favors obtaining the psychosocial component that brings the personal and environmental barriers to the fore. When the patient and the professional have equal control of the communication, a mutual relationship exists. This mutual relationship is considered ideal. This system of care and communication approach to CP is changing the relationship of parents to members of their child’s medical team at every level. The collaboration of families and medical professionals is now recognized as a best practice for many other disorders, including autism, muscular dystrophy, and cystic fibrosis. These collaborative partnerships have resulted in measurable and direct positive benefits for families, children, and medical providers.

These issues may be considered in light of a set of positive principles that inform the style of communication in the medical encounter. Communication should serve the patient’s need to tell the story and the doctor’s need to hear it; highlight the knowledge and insight of the patient about illness and well-being; reflect the doctor’s understanding of the connection between mental and physical health; proceed in a way that gives the doctor a chance to use experience and expertise to assist the child and the family; take into account the emotional impact of the encounter; be an opportunity to negotiate what is desired by both patient and physician; overcome stereotyped roles; and strengthen the relationship of patient and physician. When positive communication is encouraged, physicians elicit personal factors that affect rehabilitation. By understanding the parent’s knowledge-base, the physician can suggest appropriate educational and parental support.

Importance of parent’s networks

Parents raising a child with CP often experience anxiety, frustration, and isolation. It can be overwhelming to navigate the medical and educational systems, and sometimes the legal system, along with completing the tasks of daily life. Sharing experiences with others in similar circumstances is a source of relief and lessens the sense of isolation. There is an automatic understanding of the visceral and practical issues that accompanies being a caregiver of a child with CP. It is because of this “automatic understanding” that parents of children with CP prefer to receive emotional support from other parents who have had or who are having the same or similar experiences.

Medical and rehabilitation services for children with CP are generally time limited, whereas the family and the community are constants in a child’s life. Drawing effectively on parent and community resources enhances the likelihood that medical and therapeutic treatments combined with family support will promote better outcomes. Professionals and families working together can create home- and community-based alternatives that supplement formal services and provide structure, nurturing, and support. As budgets shrink and needs grow, parent advocacy and involvement can help decrease the workload of the professional by expanding the treatment options.

Importance of parent’s networks

Parents raising a child with CP often experience anxiety, frustration, and isolation. It can be overwhelming to navigate the medical and educational systems, and sometimes the legal system, along with completing the tasks of daily life. Sharing experiences with others in similar circumstances is a source of relief and lessens the sense of isolation. There is an automatic understanding of the visceral and practical issues that accompanies being a caregiver of a child with CP. It is because of this “automatic understanding” that parents of children with CP prefer to receive emotional support from other parents who have had or who are having the same or similar experiences.

Medical and rehabilitation services for children with CP are generally time limited, whereas the family and the community are constants in a child’s life. Drawing effectively on parent and community resources enhances the likelihood that medical and therapeutic treatments combined with family support will promote better outcomes. Professionals and families working together can create home- and community-based alternatives that supplement formal services and provide structure, nurturing, and support. As budgets shrink and needs grow, parent advocacy and involvement can help decrease the workload of the professional by expanding the treatment options.

Who benefits?

A quantitative study of parent-to-parent support groups showed that parents who participated in these groups had a greater increase in measures of cognitive adaptation and coping than parents in a control group. In addition, 89% of parents reported that the program was helpful. Families report that after becoming involved with organizations such as Reaching For The Stars. A Foundation of Hope for Children with Cerebral Palsy ( www.reachingforthestars.org ), Pathways, Easter Seals, and United Cerebral Palsy, they receive services earlier, identify more community resources, and understand parenting issues more clearly. The Beach Center on Disability at the University of Kansas ( www.beachcenter.org ), a respected research institution, Family Support America ( FamilySupportAmerica.org ), and the National Federation of Families for Children’s Mental Health ( ffcmh.org ) all acknowledge the benefits of family involvement and advocacy ( Box 1 ).