A History of Hip Surgery

David W. Anderson

Harry E. Rubash

With Commentary by William H. Harris

Introduction

During the early period of modern medicine, the ability to perform even the simplest surgeries on the hip was complicated by lack of proper anesthesia and improper aseptic technique. Prior to the introduction of anesthesia and antiseptic precautions, the success rate of any operation on the hip was so low that such procedures were limited to the treatment of severe trauma or massive infection. Anesthesia was introduced in 1847, and, although somewhat elementary by today’s standards, permitted more care and consideration when performing an operation. The introduction of the antiseptic method in 1865 by Lister provided surgeons with a reprise from the frustration of watching their patients suffer with the agony of infection common in the early days of surgery. The continuous decrease in the incidence of perioperative infection is still a hallmark of today’s surgical teaching and evolution of our practice.

Evidence of the many problems associated with early hip surgery was well described in the 1870s, when the Army Medical Museum began cataloging their vast collection of anatomic and surgical specimens. Many of these specimens illustrate the injuries and diseases which produced disability and death during war. Otis (1), in 1878, described a common scenario of his time with the following patient who developed osteomyelitis of his hip. “In January, 1872, a rising made its appearance on the thigh, about three inches below the hip-joint, which has been discharging yellowish, watery matter, and sometimes hard lumps of matter streaked with blood and sometimes clotted like cold bruised blood. Several pieces of bone have been discharged through the opening below the hip-joint. The largest piece is about the size of the little finger, and nearly a quarter of an inch thick. The doctors tell me I ought to go to some hospital and have my leg split open and the bone scraped, and they think by these means I would get well. They say it ought to be done by a surgeon experienced in such cases, but I do not know what would be best, and hope that you will give me your best and kindest advice on the subject. I am certainly in great need of relief” (1). Eventually, this patient underwent resection of his proximal femur and the procedure is briefly described as follows. “On November 18th the patient was anaesthetized by chloroform, and the head and seven inches of the upper [portion of the] extremity [femur] were excised by Professor Hunter McGuire. The operation lasted one and a half hours. The wound was dressed with dilute carbolic acid in olive oil, one part to forty, and oakum” (1). The postoperative period was nearly as tenuous as the surgery in these days, with pain controlled by “whisky and half-grain doses of morphia every six hours” (1). Otis’ description of this scenario in 1872 goes on to describe the onset of great mental depression, followed by progression of infection, sepsis, and finally death of the patient, only 12 days after his operation. The results of improvements in modern hip surgery, including anesthesia, preoperative and postoperative care, antibiotics, deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis, and especially the aseptic operating room ritual, have greatly reduced the risk of surgery on the hip. Although this has encouraged the widespread acceptance of elective surgery about the hip, today’s hip surgeons should remember that prior to modern advancements, the prospect of operating on the hip deterred even the most aggressive surgeons.

The development of hip surgery was closely associated with the treatment of tuberculosis. Tuberculous joint disease was the most common indication for operative intervention of the hip, with the exception of trauma and an occasional case of acute hematogenous arthritis, until the introduction of effective antibiotics at the end of World War II. Reports from the early 19th century discuss the difficulties with diagnosis and surgical treatment involved in tuberculosis in the large joints (2,3). Various attempts were made at preserving joint motion as well as ankylosis of the joint. Certainly, the presence of systemic tuberculosis greatly influenced the operative mortality, postoperative mortality, and long-term survival associated with any surgery on the tuberculous hip.

Pediatric indications for surgery on the hip included open reduction of congenital dislocations of the hip, infection, treatment for acute fractures, and fracture nonunions of the femoral head and neck. The development of surgery on the hip in children also coincided with the treatment of tuberculosis of the hip and pelvis, as in adults. The development of radiographs greatly improved operative indications and techniques in both adults and children. Prior to antibiotics and improvements in anesthetics and operating room technique, the treatment of tuberculosis of the hip remained essentially conservative. As described in 1948, the mainstays of treatment included “prolonged rest, fixation of the joint, good food, fresh air, sunlight, and other aids to the improvement in general condition and the building up of resistance to infection” (4). Currently, tuberculosis of

the hip accounts for approximately 15% of osteoarticular tuberculosis worldwide (5). Treatment comprises multidrug antituberculous chemotherapy for 12 to 18 months and supervised mobilization with active-assisted non–weight-bearing exercises of the involved joint through the period of healing. Operative intervention is required when the patient does not respond to 4 to 5 months of medical treatment. Surgical options include synovectomy and debridement early, followed by excisional arthroplasty if this is nonsatisfactory. Joint replacement should not be considered unless the disease is quiescent for at least 10 years (6). There has recently been a resurgence of patients who are immunocompromised, leading to increased diagnosis of tuberculosis worldwide. Lessons from a century of treating tuberculosis of the hip are abundant in the literature of earlier publications and textbooks on orthopedic surgery.

the hip accounts for approximately 15% of osteoarticular tuberculosis worldwide (5). Treatment comprises multidrug antituberculous chemotherapy for 12 to 18 months and supervised mobilization with active-assisted non–weight-bearing exercises of the involved joint through the period of healing. Operative intervention is required when the patient does not respond to 4 to 5 months of medical treatment. Surgical options include synovectomy and debridement early, followed by excisional arthroplasty if this is nonsatisfactory. Joint replacement should not be considered unless the disease is quiescent for at least 10 years (6). There has recently been a resurgence of patients who are immunocompromised, leading to increased diagnosis of tuberculosis worldwide. Lessons from a century of treating tuberculosis of the hip are abundant in the literature of earlier publications and textbooks on orthopedic surgery.

The increasing life expectancy and maturation of the so-called “baby-boomer” generation have impacted the demand for total joint arthroplasty because of the volume of patients with chronic joint disease. After World War II, the demand for relief of pain and disability from various arthritic conditions of the large joints has led to the development and refinement of operations including osteotomies, fracture fixation, and arthroplasty to help remedy these problems. Modern hip surgery had its roots in the 19th century, followed by some of the greatest achievements only in the last half-century.

Amputation at the Hip Joint

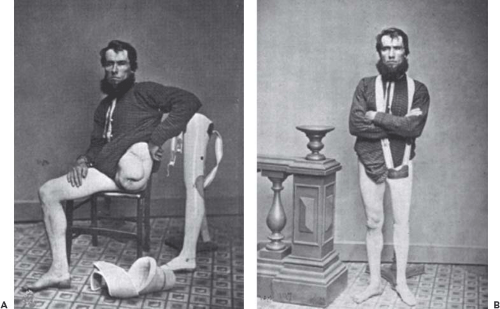

For the surgeons of the 18th and 19th centuries, amputation of the lower extremity through the hip joint presented challenges in both concept and implementation. Sauveur Francois Morand, a student of Cheselden and a surgeon at La Charite in Paris, was the first surgeon documented to seriously consider the possibility of carrying out such an amputation in 1729 (7). In the subsequent decades, there are a number of published case reports and case series regarding the possibility of performing such a procedure and attempts to improve patient morbidity and mortality rates. There are additional numerous discussions regarding the ethics of such a mutilating and dangerous procedure. Subsequently, anecdotal reports of hip disarticulation for wounds and for infection, particularly tuberculosis, accumulated. In 1812, for example, Larrey (8) described a successful amputation through the hip joint in an officer of the dragoons wounded by a missile in a battle before Moscow. Astley Cooper successfully carried out an elective disarticulation of the hip in 1824 in a 40-year-old patient with a chronic infection involving the whole upper end of the femur (9,10). The American Civil War (1861–1865) played a special role in the discovery and development of many of the early principles of orthopedic surgery. At the time of the War, orthopedic surgery was not yet a recognized specialty in the United States. The War began in a time when antibiotics, principles of fluid resuscitation, surgical implants, and diagnostic tools such as radiographs were not available. The study and treatment of extremity trauma during this era provided many of the basic orthopedic techniques that are still in use today, including Buck traction and plaster splints. Injuries to the hip caused the highest mortality of all the skeletal injuries, with mortality rates approaching 90% (11). By 1867, with 111 elective disarticulations of the hip with 46 survivors, a mortality rate of 57% was reported (12). During the Civil War (1861–1865) there were 19 primary disarticulations of the hip for missile wounds with a mortality rate of 95%; 9 secondary disarticulations with a mortality rate of 78%; and 7 cases of reamputation with a mortality rate of 43% (13). An example of a typical patient and good outcome are presented in Figure 1.1 (14). During the next century the operative mortality for all types of hip disarticulation continued to drop, reaching an acceptable level after World War II. Hip disarticulation has remained in the surgical armamentarium primarily as a tool for the control of malignant tumors of the bone and soft tissue, and rarely for trauma. The basic technique of the operation was well described by Boyd in 1947 (15).

Hip Joint Resection

Although disarticulations through the hip joint were uncommon, other amputations for trauma and infection were carried out frequently during the 18th century. Tuberculous infections were the predominant cause of chronic infection and infection-related morbidity reported during the 18th century. Mindful surgeons, however, began to consider the possibility of limb-sparing operations. On February 9, 1769, at a meeting of the Royal Society, Charles White (16) described the case of a 14-year-old boy with a large abscess, probably tuberculous, in his left shoulder. He treated the patient by drainage of the abscess and resection of the necrotic portion of the upper end of the humerus. The result was as favorable as it was surprising, with preservation of the arm and a high level of function. White never carried out a hip joint resection on a living patient; however, he did carry out such an operation on a cadaver and proved to his satisfaction that it was feasible. The substitution of joint resection for amputation was popularized by Park and Moreau (12). James Syme (17) was an ardent advocate of joint resection but believed that it was not a feasible operation at the hip. It was not until 1822 that a hip joint resection was carried out in a 9-year-old male patient with a chronic abscess of the joint with dislocation of the head of the femur by Anthony White (18) at Westminster Hospital, London. Postoperatively the deformity was corrected and the patient was treated as for an open fracture using a long splint. Although this left the patient with one leg considerably shorter than the other, some mobility was restored to the joint. Twelve months later the wound had healed and the patient had regained a remarkable level of function. Interestingly, Anthony White is also credited as the first to give an account of phlegmasia alba dolens, or deep vein thrombosis, of an extremity (19). His obituary in the Lancet in 1849 gave his contemporaries the ability to honor him with being perhaps “the most eminent surgeon by much in the North of England” (20).

Joint resection was the first orthopedic operation for which special instrumentation was developed. Moreau (12) had a flexible saw, “with joints like the chain of a watch,” constructed by an instrument maker in London in 1790. This was passed around the bone by means of a large needle. Bernhard Heine of Wurzburg took this idea a step farther

when in 1832 he developed his “chain osteotome” (21). This progenitor of the present ubiquitous chain saw was considered a real advance because it allowed division of the bone quickly through a small incision. Heine received the important Monthyon Prize in Paris for this invention in 1835. Heine also carried out extensive animal experiments studying the process of regeneration of bony tissue following resection (22). Louis Ollier of Lyon also used the operation of resection as a means of studying bone regeneration and the function of the periosteum, both in his patients and in experimental animals. His two-volume work on these subjects gives a good description of the operation of hip resection in a patient (23). By the middle of the 19th century resection of the hip joint was well accepted, being described by Erichsen (24) as “not difficult in performance”. Postoperatively the patients were managed by being placed in a long splint.

when in 1832 he developed his “chain osteotome” (21). This progenitor of the present ubiquitous chain saw was considered a real advance because it allowed division of the bone quickly through a small incision. Heine received the important Monthyon Prize in Paris for this invention in 1835. Heine also carried out extensive animal experiments studying the process of regeneration of bony tissue following resection (22). Louis Ollier of Lyon also used the operation of resection as a means of studying bone regeneration and the function of the periosteum, both in his patients and in experimental animals. His two-volume work on these subjects gives a good description of the operation of hip resection in a patient (23). By the middle of the 19th century resection of the hip joint was well accepted, being described by Erichsen (24) as “not difficult in performance”. Postoperatively the patients were managed by being placed in a long splint.

In the United States, Lewis Sayre became the great exponent of hip joint resection for chronic infections. His first such procedure, carried out in 1854, was on a 9-year-old girl with “morbus coxarius,” probably tuberculosis. The case was thoroughly discussed in his lectures (25). Accompanying this report is an analysis of 59 of his hip resections with 39 survivors. Eight patients died during the immediate postoperative period. The remainder died of late complications, usually of tuberculosis. Sayre toured Europe discussing hip resection and was decorated by the Norwegian Crown for his work. In 1876, at the International Medical Congress in Philadelphia, Sayre demonstrated the operation before a group of surgeons including Lister (26). Gibney (27), in New York, supported Sayre and recognized the value of the operation in preventing and even reversing the progress of “lardaceous degeneration” or secondary amyloidosis, a common cause of death in bone and joint tuberculosis. Volkmann (28), in Leipzig, was more conservative and believed that hip resection should be done only as a life-saving procedure. The French surgeons also maintained a very conservative attitude toward hip joint resection for tuberculosis, Calot (29) believing it to be a bad operation.

More recently, the surgeon most closely identified with the procedure known as hip joint resection was Gathorne Robert Girdlestone in Oxford (Fig. 1.2). In his book on bone and joint tuberculosis published in 1940, Girdlestone (30) outlined the essential steps of the operation described as follows: (a) A complete exposure of the anterior and upper aspect of the joint, (b) excision of the capsule and synovia, (c) division of all structures inserted into the greater trochanter, (d) dislocation of the remains of the head of the femur and cleaning out the acetabulum, and (e) a transverse osteotomy usually just above the lesser trochanter depending on the site of the disease. Postoperatively the patients were treated in

traction on a frame. The control of tuberculosis by the use of antibiotic drugs has almost left this operation without an indication except as a salvage operation in cases of infected prostheses. In addition to applying this operation to tuberculous and other infected cases, Girdlestone (31) also used it in some cases of severe bilateral osteoarthritis of the hips, simply resecting the head and neck of the femur to gain mobility.

traction on a frame. The control of tuberculosis by the use of antibiotic drugs has almost left this operation without an indication except as a salvage operation in cases of infected prostheses. In addition to applying this operation to tuberculous and other infected cases, Girdlestone (31) also used it in some cases of severe bilateral osteoarthritis of the hips, simply resecting the head and neck of the femur to gain mobility.

Arthrodesis

Although hip fusion may be an unfamiliar operation to many recently trained orthopedic surgeons, the concept of stiffening a joint to provide stability to a joint and preserve function was introduced in 1882 by Eduard Albert (Fig. 1.3) (32) who carried out an ankle fusion in a patient with postpoliomyelitis paralysis. The concept was quickly taken up by other surgeons. Cases of fusion of the hip for old congenital dislocations of the hip were described in 1885 by Heusner and Lampugnani (33,34). Hip arthrodesis initially found its greatest use, however, in the treatment of tuberculous joint disease. Clinicians had observed, over long periods of time, that an occasional case of tuberculous joint disease ceased to progress when the affected joint became stiff. A good deal of conservative treatment was directed at production of a spontaneous ankylosis with the use of splints and frames. Hugh Owen Thomas (Fig. 1.4), whose treatment of hip disease was based on the dictum, “rest, absolute, uninterrupted, and prolonged,” considered that a good end result of his treatment was an ankylosed hip situated in the best possible functional position (35).

Surgical arthrodesis of a tuberculous joint was not carried out until 1911 when Russell Hibbs of New York (Fig. 1.5) reported such an operation in a patient with tuberculosis of the knee. In the knee, it is possible to surgically resect the articular cartilage of the joint and oppose to largely flat, congruent cancellous bone surfaces. However, in the hip, the surgeon is left with limited areas of apposing cancellous bone surfaces after denuding the cartilage of the femoral head and acetabulum. In case of tuberculosis, it was deemed advisable to avoid entering the joint because of the infectious nature of the disease. This was the impetus for the development of the many extra-articular methods of hip fusion that have been described. Hibbs (2) reported preliminary results after an extracapsular hip fusion for tuberculosis in which he advanced the greater trochanter upward to impinge on the pelvis in 1926.

Variations of this technique of bridging the space between the greater trochanter and wing of the ilium with a graft either from the trochanter or ilium have been reported by many surgeons (27,36,37). Biomechanically, all of these grafts were put under tension. Because of failure of the tension methods, other operations were quickly devised for extra-articular hip fusions where the grafts were under compression.

Variations of this technique of bridging the space between the greater trochanter and wing of the ilium with a graft either from the trochanter or ilium have been reported by many surgeons (27,36,37). Biomechanically, all of these grafts were put under tension. Because of failure of the tension methods, other operations were quickly devised for extra-articular hip fusions where the grafts were under compression.

In the absence of sepsis, intra-articular fusions may be performed, including indications such as advanced osteoarthritis and old congenital deformities. Historically, there are various methods which merit mention in the discussion about hip arthrodesis. One of the simplest techniques was that of Watson-Jones (38), who simply drove a long triflanged nail up the femoral neck and across the joint into the acetabulum. This was useful only in patients with a minimal amount of motion and deformity. Figure 1.6 shows the technique of hip joint arthrodesis as described by Watson-Jones in 1956. John Charnley (Fig. 1.7) improved on this technique by shaping the head of the femur and dislocating it centrally into a hole in the acetabulum, which was termed central stabilization of the hip (39). Although the clinical results of this were satisfactory to most patients, there were complications including discomfort, femoral neck fractures, and failure to achieve bony union. Advances in internal fixation of fractures and the introduction of very large plates benefited hip fusion techniques, including the introduction of the Cobra plate, thereby providing excellent fixation of the ilium to the upper femoral shaft (40). Currently, there are several techniques for hip fusion with various benefits and limitations. Overall long-term results depend on proper surgical technique, adequate hip positioning, minimal limb-length discrepancy, and proper patient selection.

Osteotomy

In the evolution of surgery about the hip, indications were expanded beyond infection and trauma. As surgeons became more experienced, the presence of deformity and/or functional impairment because of conditions involving the hip joint stimulated them to devise new operations. In contrast to amputations and resections, osteotomies of the hip were useful in many conditions and were helpful in treatment to correct deformity, as well as operations to produce deformity, to increase function.

John Rhea Barton of Philadelphia (Fig. 1.8) performed the first osteotomy of the hip on November 22, 1826 (41,42). His patient, a 21-year-old sailor, had been injured in a fall at sea 20 months previously, suffering an injury variously diagnosed as a contusion of the hip, a dislocation, or

a fracture. At the time he was seen by Barton, the hip was ankylosed in severe flexion and adduction and there was considerable swelling about the hip joint. After observing him in the hospital for almost a year, Barton carried out his carefully planned operation. Having had a strong narrow saw manufactured for the purpose, Barton made a short muscle-splitting incision over the upper end of the femur and divided the bone at the level of the base of the neck of the femur. Postoperatively the wound healed by secondary intention with only one bout of erysipelas. The deformity was corrected and a deliberate effort was made to keep the osteotomy from healing so as to produce a pseudoarthrosis. Four months after the operation the patient was able to walk and had a useful range of motion in his hip.

a fracture. At the time he was seen by Barton, the hip was ankylosed in severe flexion and adduction and there was considerable swelling about the hip joint. After observing him in the hospital for almost a year, Barton carried out his carefully planned operation. Having had a strong narrow saw manufactured for the purpose, Barton made a short muscle-splitting incision over the upper end of the femur and divided the bone at the level of the base of the neck of the femur. Postoperatively the wound healed by secondary intention with only one bout of erysipelas. The deformity was corrected and a deliberate effort was made to keep the osteotomy from healing so as to produce a pseudoarthrosis. Four months after the operation the patient was able to walk and had a useful range of motion in his hip.

Bernard Langenbeck (43), the leading German surgeon of his generation, was aware of Barton’s work and, based on this knowledge and the experience with bone surgery gained during a war in 1848, developed his method of subcutaneous osteotomy. Through a small incision, a drill was used to perforate the bone. A sharp-pointed narrow saw was inserted into the drill hole and used to partially divide the bone. When the bone was weakened sufficiently, the remainder was broken through by manipulation. Langenbeck applied his method to old ricketic deformities of the tibia.

Mayer (44) published a major paper on osteotomy in 1856. He reported his experience in his clinic in Wurzburg with 17 patients including an 8-year-old girl in whom he carried out a high femoral osteotomy for an ankylosed hip. He derived the operation from other subcutaneous operations introduced by Delpech and Stromeyer and reviewed the experience of European and American surgeons. Lewis Sayre (45,46) reported two cases of osteotomy through the trochanteric region with the aim of producing an “artful pseudarthrosis” in 1863.

Richard Volkmann, a friend and admirer of Lister, was the first surgeon to carry out osteotomies using antiseptic precautions. This was reported in 1875 (47). In 1879, William Adams (48) reviewed the subject of osteotomy as it was carried out in England. He adopted Lister’s antiseptic technique only after Ogston in Aberdeen had done the first such case in Britain in 1876. The London surgeon Gant (49) was an early proponent of osteotomy of the femur just below the lesser trochanter for fixed deformities of the hip. As a result of his experience with the treatment of congenital dislocations of the hip and the treatment of old wounds of the hip during World War I, Lorenz (Fig. 1.9) (50) devised his bifurcation osteotomy to correct deformity and to restore stability during weight bearing. Henry Milch of New York (Fig. 1.10) became interested in Lorenz’s osteotomy and did a great deal to explain the biomechanics of its success. In 1941, Milch reported two patients with ankylosis of the hip in whom, to regain useful motion, he had resected the femoral head and neck and performed a high femoral “pelvic support” osteotomy (51,52). This operation has also been performed by other surgeons with success (53). Through his work, the procedure became a staple of the orthopedic armamentarium (51,54,55,56,57). This osteotomy had wide application and became the prototype of the high femoral pelvic support osteotomies.

Skeletal fixation of the osteotomy fragments was a relatively late development. In the early progression of osteotomies, patients were immobilized in splints, in traction, or with the use of plaster of Paris dressings. It was not until

1924 that Schanz (Fig. 1.11) (58) described the use of external skeletal fixation to control and immobilize the components of his osteotomy. Two large screws were placed, one above and one below the line of the osteotomy before dividing the bone. After the osteotomy, the ends of the screws were brought out through the wound and held in place by a special clamp. This form of external skeletal fixation gave good control of the fragments and introduced more precision into the operation, but still relied on the use of a plaster of Paris spica. Originally designed for the treatment of congenital dislocations of the hip, Schanz (59) soon adapted his operation to the treatment of old ununited fractures of the neck of the femur. The level of the femoral osteotomy as carried out by Schanz varied with each case but was almost always below the lesser trochanter.

1924 that Schanz (Fig. 1.11) (58) described the use of external skeletal fixation to control and immobilize the components of his osteotomy. Two large screws were placed, one above and one below the line of the osteotomy before dividing the bone. After the osteotomy, the ends of the screws were brought out through the wound and held in place by a special clamp. This form of external skeletal fixation gave good control of the fragments and introduced more precision into the operation, but still relied on the use of a plaster of Paris spica. Originally designed for the treatment of congenital dislocations of the hip, Schanz (59) soon adapted his operation to the treatment of old ununited fractures of the neck of the femur. The level of the femoral osteotomy as carried out by Schanz varied with each case but was almost always below the lesser trochanter.

Blount (60), of Milwaukee, (Fig. 1.12) first described an effective system of internal fixation for high femoral osteotomies in 1943. Using his blade plate in many configurations, Blount was able to precisely plan and carry out a wide variety of osteotomies and fix them well enough that no additional splints or spicas were required. The patients could be allowed out of bed and became ambulatory with aides shortly after the operation. As techniques of internal fixation improved, the internal fixation of the osteotomy fragments became even more secure (61). Such internal fixation permitted exact planning for the final angulation and/or displacement of the bony fragments and insured against any change in the desired configuration during the healing process, while at the same time permitting the patient to be active.

Osteotomies of the femur and pelvis have become important procedures in the management of patients with congenital dislocations of the hip. The reduction of an old congenital dislocation of the hip by means of an operation was first described by Alfonso Poggi of Bologna in 1880 (62). The open reduction of congenital dislocations of the hip was popularized by Albert Hoffa (63,64) who believed that it should be carried out early, in young children, rather than be delayed. The anterior approach as described by Salter (Fig. 1.13) became the most commonly used avenue through which open reduction was accomplished (65,66,67,68). An alternative medial approach was developed by Ludloff (69). This has remained a very viable option (70). As an aid to the reduction, Swett (71) described an osteotomy of the shaft of the femur that shortened it. Osteotomies were also carried out to correct rotation deformities of the upper end of the femur after a reduction had been obtained (72).

In the early years of the 20th century, few children with congenital dislocations of the hip had open reductions because the diagnosis was usually made late and the results of open reduction in late cases were not satisfactory. With the introduction of the x-ray and with increasing emphasis on early diagnosis, open reduction during the first year of life became the usual treatment if closed reduction could not be accomplished.

The bifurcation osteotomy of Adolf Lorenz (50) was widely used in older patients whose hips could not be reduced. In this operation, the position of the dislocated head of the femur

remained unchanged; the oblique osteotomy took place at the level of the acetabulum, and the proximal end of the distal fragment was placed in the acetabulum (73). As the osteotomy healed, the bone spike placed in the acetabulum atrophied, and the end result was a high pelvic support osteotomy. Schanz (58,59) carried out his osteotomy through the shaft of the femur more distally, at the level of the ischial tuberosity.

remained unchanged; the oblique osteotomy took place at the level of the acetabulum, and the proximal end of the distal fragment was placed in the acetabulum (73). As the osteotomy healed, the bone spike placed in the acetabulum atrophied, and the end result was a high pelvic support osteotomy. Schanz (58,59) carried out his osteotomy through the shaft of the femur more distally, at the level of the ischial tuberosity.

Operations for the treatment of congenital dislocations of the hip were also carried out on the acetabular side. The first of these were designed to cover the head by extending the acetabular roof laterally by means of the “shelf operation.” In 1915, Albee (Fig. 1.14) (74) described an operation to stabilize paralytic and congenital dislocations of the hip that consisted of turning down the lateral roof of the acetabulum and maintaining its position by means of a bone graft. Among the surgeons who modified and popularized the shelf operation, Gill (75,76,77,78,79,80) of the University of Pennsylvania was the most prominent. In spite of its apparent inadequacy, the long-term results of such operations were surprisingly good (81). The operations of Pemberton, Steele, Chiari, and Salter were all directed to providing better coverage of the femoral head by means of turning down the roof of the acetabulum, displacing the acetabulum medially, or reorienting the entire acetabulum (65,66,67,68,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90).

Osteotomies of the upper end of the femur, in addition to being useful in the management of hip problems in infants and children, proved to be of great value in the management of osteoarthritis of the hip in adults. In Vienna, Haas (91), an associate of Lorenz, applied the bifurcation osteotomy to the treatment of osteoarthritis of the hip with some success. In Great Britain both Malkin and McMurray (92,93) had similar results.

McMurray (94,95) of Liverpool (Fig. 1.15) is generally credited with popularizing high femoral osteotomy for treatment of osteoarthritis. In 1939 he reported on a series of 42 patients on whom he had carried out an oblique osteotomy through the intertrochanteric region of the femur with displacement of the distal fragment medially. He believed that the operation favorably affected the weight-bearing line, relieving the hip from stress, and exposing a new portion of the articular surface of the head of the femur to the articular surface of the acetabulum. The patients were immobilized in a plaster of Paris spica cast postoperatively. The introduction of effective internal fixation quickly made it possible to discard the spica cast and improved the convalescence. Many types and techniques of high femoral osteotomies were used in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the hip (96,97,98). By improving joint congruency and limb alignment and by redistributing forces across the hip, osteotomy can provide long-lasting improvement and offer a biologic alternative to total hip replacement in well-selected patients.

The relief of pain gained by these operations was generally satisfactory and lasting. Interestingly enough, the success of the operation did not depend on the degree of displacement of the osteotomy. The important factor appeared to be the complete

division of the femur (99,100). This, coupled with the immediate relief of hip pain following the operation, pointed to circulatory changes in the proximal fragment, rather than mechanical factors, as the cause of the improvement. There was good evidence to indicate that repair of the articular cartilage of the head of the femur occurred months and years following the osteotomy (101). The value of high femoral osteotomy for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the hip can be assessed by this statement of the well-known total joint surgeon William H. Harris of Boston, writing in 1995: “On the basis of its clinical results, and because of the well known adverse effects of hip replacements in young patients, osteotomy remains the preferred operative procedure in patients who are suitable candidates and who are less than forty-five to fifty years old” (101). The usefulness of the high femoral osteotomies extended to yet another problem, as we shall see when we discuss the treatment of fractures of the neck of the femur.

division of the femur (99,100). This, coupled with the immediate relief of hip pain following the operation, pointed to circulatory changes in the proximal fragment, rather than mechanical factors, as the cause of the improvement. There was good evidence to indicate that repair of the articular cartilage of the head of the femur occurred months and years following the osteotomy (101). The value of high femoral osteotomy for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the hip can be assessed by this statement of the well-known total joint surgeon William H. Harris of Boston, writing in 1995: “On the basis of its clinical results, and because of the well known adverse effects of hip replacements in young patients, osteotomy remains the preferred operative procedure in patients who are suitable candidates and who are less than forty-five to fifty years old” (101). The usefulness of the high femoral osteotomies extended to yet another problem, as we shall see when we discuss the treatment of fractures of the neck of the femur.

Fractures of the Hip

The treatment of fractures about the hip has presented a problem for physicians since the time of Hippocrates. Until the introduction of internal fixation for displaced femoral neck fractures in the 1930s, there was considerable truth to the phrase: “We come into this world under the brim of the pelvis and go out through the neck of the femur” (102). Prior to the introduction of radiographs, all hip fractures were lumped together without clear understanding of why some fractures healed and others failed to unite. In 1822, Astley Cooper (103) classified hip fractures as intracapsular or extracapsular on the basis of their blood supply and stated that he had never seen a healed intracapsular fracture. Royal Whitman, in the early 20th century, described obtaining reduction by manipulation and placing these fractures in abduction and marked internal rotation with a plaster spica cast for definitive treatment (104). Newton Schaffer, around 1886, was probably the first to treat these fractures by immobilization in an abduction brace; however, most of these fractures did not heal (105). In 1857, the American surgeon Frank Hastings Hamilton (106) reviewed the results of 39 fractures in hips, both intracapsular and extracapsular, and found the treatment results to be “imperfect.” Observations by two well-known surgeons in the mid-19th century, long before radiographs were available, helped guide the early principles leading to surgical treatment of hip fractures. Robert Smith (107), in 1854, wrote that, “Osseous union of intracapsular fractures is most likely to occur when the fracture is impacted.” Henry J. Bigelow (108), at Massachusetts General Hospital in 1869, indicated that a false joint was a frequent result of an unimpacted fracture. The observations by these and other clinicians were paramount to the development of modern principles of internal fixation of fractures about the hip.

At a meeting of the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Chirurgie in April 1878, Bernard Langenbeck (109) described the open reduction and internal fixation of an ununited extracapsular hip fracture with a silver-plated metal screw. At the same meeting, Friedrich Trendelenburg (110) presented his case of a man with a fresh extracapsular fracture of the hip that he had openly reduced and fixed with an ivory peg. Although there are other anecdotal reports of this type, it was Nicolas Senn (111,112) of Chicago who demonstrated that (a) intracapsular fractures of the hip sometimes healed and (b) internal fixation of such fractures in cats could result in healing. On the basis of these reports in 1883, Senn urged open reduction and internal fixation as a definitive treatment for both intracapsular and extracapsular hip fractures. However, in view of the strenuous opposition of all of his surgical colleagues, he abandoned his proposal. As open surgical treatment was looked upon so poorly at this time because of poor methods of fixation, there remained an attitude of defeatism for treatment of this injury during the late 19th century.

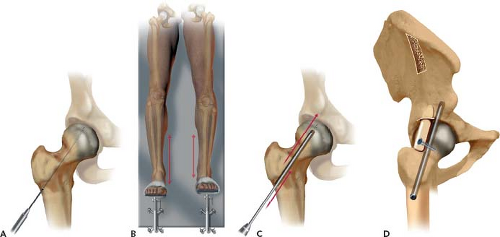

In 1916, Royal Whitman (105) of New York demonstrated that the reduction and immobilization of intracapsular hip fractures by means of a hip spica could lead to healing in a substantial number of patients. Dissatisfaction with the cumbersome plaster immobilization spurred surgeons to explore better methods. In 1915, Fred Albee (113) of New York began to carry out open reduction and internal fixation of intracapsular fractures using anterior and lateral incisions. The fracture was fixed with a bone graft taken from the patient’s tibia. Hey-Groves (114) of Bristol carried out similar operations using pegs of ivory and beef bone as well as autogenous grafts for fixation. With the introduction by Sherman (115) of stainless steel surgical appliances in 1912, the use of other materials for fixation was gradually phased out. In 1917, Smith-Petersen of Boston (116) (Fig. 1.16) combined the anterior and lateral incisions into one larger incision that gave exposure to the entire upper end

of the femur. Through this incision he was able to open the capsule of the hip joint, reduce the fracture, and insert a nail through the lateral cortex of the trochanter. To fix the fracture, Smith-Petersen designed a triflanged nail which more effectively prevented rotation of the fragments (117,118,119,120). With the new nail design came advancement in surgical technique and improvements to operating theater instrumentation and tables. For the first time, intraoperative radiographs were used to determine the position of the fracture fragments and the fracture table was designed and improved for assistance with reduction of the fracture (121). The addition of a central hole to the original Smith-Petersen nail by Sven Johansson (122) greatly improved the ease of placing the nail because it could be inserted over a guide pin through a small lateral incision. The result of this evolution was to make closed reduction and internal fixation of fractures of the neck of the femur the standard method of treatment (123).

of the femur. Through this incision he was able to open the capsule of the hip joint, reduce the fracture, and insert a nail through the lateral cortex of the trochanter. To fix the fracture, Smith-Petersen designed a triflanged nail which more effectively prevented rotation of the fragments (117,118,119,120). With the new nail design came advancement in surgical technique and improvements to operating theater instrumentation and tables. For the first time, intraoperative radiographs were used to determine the position of the fracture fragments and the fracture table was designed and improved for assistance with reduction of the fracture (121). The addition of a central hole to the original Smith-Petersen nail by Sven Johansson (122) greatly improved the ease of placing the nail because it could be inserted over a guide pin through a small lateral incision. The result of this evolution was to make closed reduction and internal fixation of fractures of the neck of the femur the standard method of treatment (123).

Friedrich Pauwels (124), a student of Schanz, was one of the first to thoroughly study the biomechanics of intracapsular hip fractures and to describe a classification that had a predictive value for the prognosis. This was based on his knowledge of the effects of forces of compression, tension, and shear on fracture healing. He applied this knowledge specifically to the configuration of fractures of the neck of the femur before and after reduction, and concluded that those in a compression mode had a more favorable prognosis than those in which shear and tension predominated. In addition to emphasizing the importance of achieving a primary reduction in a compression mode, when this failed or in cases of ununited fractures, he advocated carrying out a high femoral osteotomy to produce a compression mode.

In spite of the progress that had been made, the results were far from satisfactory because of the complications of nonunion and aseptic necrosis. This was especially true in cases of fractures of the neck of the femur in children (125,126). In 1934, Kellogg Speed, in his Fracture Oration before the Clinical Congress of the American College of Surgeons, spoke of the intracapsular hip fracture as the “unsolved fracture” (127,128). Nineteen years later, in 1953, in his presidential address to the American Orthopedic Association, James A. Dickson (129) again spoke of this fracture as the “unsolved fracture.”

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree