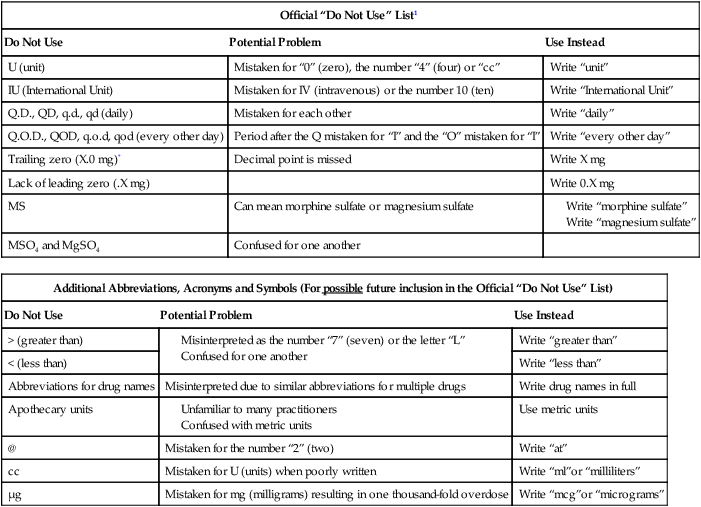

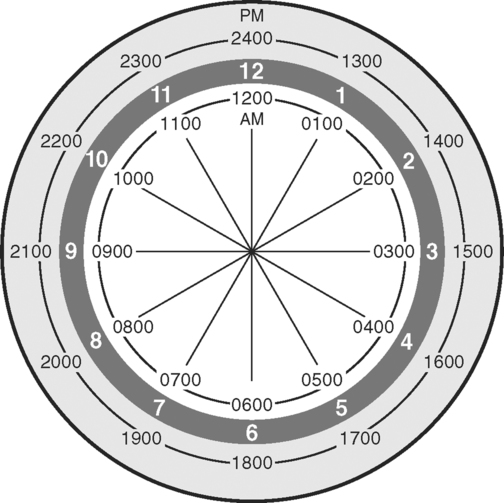

Upon successfully completing this chapter, you will be able to: • Explain the importance of written communication. • Describe 13 guidelines for charting in a medical record. • Describe the two common methods of organizing the medical record. • Describe and give examples of narrative charting using the SOAP, SOAPIE, SOAPIER, and PIE formats. • Explain how flow sheets, graphic sheets, and progress notes promote communication in a health care setting. • Describe the practical tips for communicating specific issues on a medical record. Here is a closer look at each of these reasons. In the hospital setting, peer review organizations (PRO) will examine charts to determine whether the patient’s length of stay was appropriate. Unless documentation supports additional hospital stay, the institution or setting may not be compensated for the difference. For example, assume that Paula Morrello was admitted to the hospital for pneumonia. The morning that she was to be discharged, she developed a rash and thus was kept overnight for observation. According to the Diagnostic Related Groups (DRG) (Box 7-1) standards, patients with pneumonia should be discharged in 3 days, but because of this rash this patient remained in the hospital for another day. Unless the documentation clearly states the need for the additional hospital stay, Medicare will not cover the extra day in the hospital. It will claim that it was simply “an allergic rash and that the treatment could have been managed at home” and the hospital will lose that money. Make sure you document any change in the patient’s condition that would warrant a change in the plan of care. Many health care facilities require that time entries be listed in military format. Military format is a 24-hour-clock system that allows each hour to be listed clearly without the confusion of a.m. versus p.m. (Fig. 7-1). Following is an example of a communication mishap that can occur when military time is not used. Which charting example gives a clear picture of when the patient fell? On January 1, 2004, the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) released new standards regarding the use of abbreviations within health care settings. These standards were developed to improve patient safety. Table 7-1 lists the abbreviations that may not be used. It is important to stress that this list changes periodically and the standards are updated frequently. It is your responsibility to remain current. Failure to comply with JCAHO standards can result in fines and loss of an institution’s accreditation. Table 7-1 JCAHO ABBREVIATIONS: ABBREVIATIONS THAT MAY NOT BE USED 1Applies to all orders and all medication-related documentation that is handwritten (including free-text computer entry) or on pre-printed forms. *Exception: A “trailing zero”may be used only where required to demonstrate the level of precision of the value being reported, such as for laboratory results, imaging studies that report size of lesions, or catheter/tube sizes. It may not be used in medication orders or other medication-related documentation. Following is an example of a communication mishap related to abbreviations. This sentence was charted; “Pt had normal bs this pm.” What was normal this morning? The answer is unclear and ambiguous. Here is another example. What does the abbreviation pm mean? Errors in spelling are unacceptable. They convey unprofessionalism, laziness, and poor judgment.

WRITTEN COMMUNICATION: IT’S MORE THAN JUST WORDS

IMPORTANCE OF WRITTEN COMMUNICATION

Reimbursement Documentation

ESSENTIAL GUIDELINES FOR CHARTING IN A MEDICAL RECORD

Use Military Time

Use Approved Abbreviations and Symbols

Official “Do Not Use” List1

Do Not Use

Potential Problem

Use Instead

U (unit)

Mistaken for “0” (zero), the number “4” (four) or “cc”

Write “unit”

IU (International Unit)

Mistaken for IV (intravenous) or the number 10 (ten)

Write “International Unit”

Q.D., QD, q.d., qd (daily)

Mistaken for each other

Write “daily”

Q.O.D., QOD, q.o.d, qod (every other day)

Period after the Q mistaken for “I” and the “O” mistaken for “I”

Write “every other day”

Trailing zero (X.0 mg)*

Decimal point is missed

Write X mg

Lack of leading zero (.X mg)

Write 0.X mg

MS

Can mean morphine sulfate or magnesium sulfate

MSO4 and MgSO4

Confused for one another

Additional Abbreviations, Acronyms and Symbols (For possible future inclusion in the Official “Do Not Use” List)

Do Not Use

Potential Problem

Use Instead

> (greater than)

Write “greater than”

< (less than)

Write “less than”

Abbreviations for drug names

Misinterpreted due to similar abbreviations for multiple drugs

Write drug names in full

Apothecary units

Use metric units

@

Mistaken for the number “2” (two)

Write “at”

cc

Mistaken for U (units) when poorly written

Write “ml”or “milliliters”

μg

Mistaken for mg (milligrams) resulting in one thousand-fold overdose

Write “mcg”or “micrograms”

Spell Correctly

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

WRITTEN COMMUNICATION: IT’S MORE THAN JUST WORDS

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

(female), and

(female), and  (male). These must be listed in the policy manual as well.

(male). These must be listed in the policy manual as well.