Why honor confidentiality?

Objectives

• Define the terms confidentiality and confidential information.

• Describe the concept of “need to know” as it relates to maintaining confidentiality.

• Discuss the ethical norms involved in keeping and breaking professional confidences.

• Discuss some important aspects of documentation that affect confidentiality.

New terms and ideas you will encounter in this chapter

trust

confidentiality

confidential information

right to privacy

need to know

patient care information systems (PCIS)

health information managers

the medical record

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA)

protected health information

Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act of 2009 (HITECH Act)

health record databases

panel of laboratory tests

Topics in this chapter introduced in earlier chapters

| Topic | Introduced in chapter |

| Hippocratic oath | 1 |

| Character traits or virtues | 2 |

| Codes of ethics | 2 |

| Ethical dilemma | 3 |

| Beneficence | 4 |

| Nonmaleficence | 4 |

| Fidelity | 4 |

| Autonomy | 4 |

Introduction

In this chapter and the next several chapters, you will have an opportunity to think about specific ways in which patients learn to put their trust in you. You already have met some patients through the stories that have been presented to help focus your thinking. The idea of confidentiality in health care has ancient roots as a basic building block of trust between health professionals and patients. For instance, the Hippocratic Oath, written in the fourth century BC, says,

“And whatsoever I shall see or hear in the course of my profession, as well as outside my profession…if it be what should not be published abroad, I will never divulge, holding such things to be holy secrets.”1

And so confidentiality is a splendid place to begin this focus on basic components of trust building. The story of Twyla Roberts, an occupational therapist, and Mary Louis, a patient, helps set the stage for reflection on confidentiality.

Reflection

What should Twyla do next? Why? What should she ultimately do in regard to this situation? Why?

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

Many dimensions of Twyla’s ethical quandary are identical to questions that have made confidentiality a compelling issue over the centuries. At the same time, because she lives in an era of computerized data entry, storage, and retrieval of patient information, her situation also is highly contemporary.

The goal: a caring response

In light of all you have learned about Twyla and Mary, you know that her ethical goal of finding a caring response requires her to address both traditional and contemporary dimensions of confidentiality and the specific type of confidential information that this patient has shared. She needs to be clear about what confidentiality is and its appropriate use and limits. She needs to understand the related concept of privacy and to be savvy about new challenges regarding the use of computerized networks designed to manage information about patients.

Identifying confidential information

The most commonly accepted idea of confidential information in the professions is that it is information about a patient or client that is harmful, shameful, or embarrassing. Does it necessarily have to come directly from that person? No. Information that is furnished by the patient directly, or comes to you in writing or through electronic data, or even from a third party, might count as confidential.

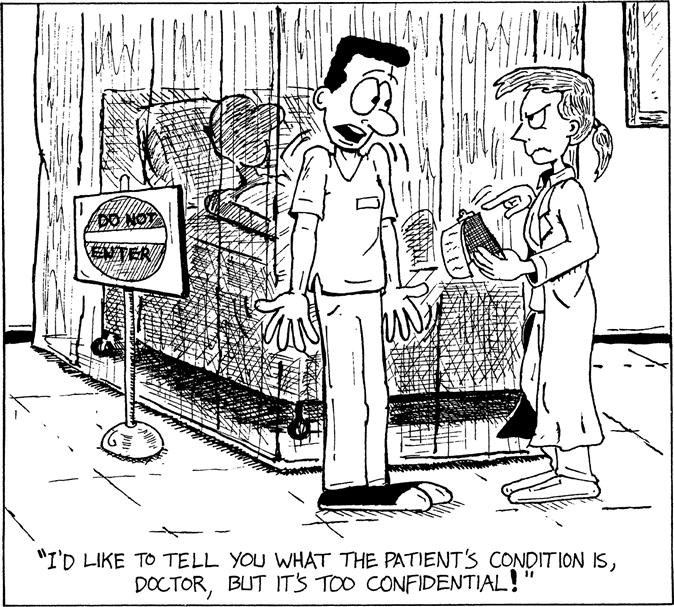

Who is to be the judge of whether information is harmful, shameful, or embarrassing? The person himself or herself is the best judge, but any time you think a patient has a reasonable expectation that sensitive information will not be spread, it is best to err on the side of treating it as confidential. Of course, as Figure 10-1 illustrates, it is possible to go to extremes so that the best interests of the patient are lost in the process. A good general rule regarding potentially confidential information is to treat caution as a virtue.

Confidentiality and privacy

Sometimes the notion of confidential information is discussed within the framework of the constitutional right to privacy.2 This framework is not incorrect because the right to privacy means that there are aspects of a person’s being into which no one else should intrude. We return to this idea of privacy later. At the same time, confidential information creates a situation a little different than privacy, taken alone.

Patients who share private information have chosen to relinquish their privacy because they have a reasonable expectation that sensitive information will be shared with certain people to further their welfare but with no one else.3 The patient thinks, “I may have to tell you something very private, perhaps something I’m ashamed of, because I think you need to know it to plan what is best for me. But I do not want or expect you to spread the word around.” There is an implicit understanding in the relationship that you, the professional, can perform your professional responsibilities only with accurate information from and about the patient. Patients and family caregivers trust that health professionals have the competency to maintain professionalism in communicating information necessary for health care delivery.

When you have confidential information from patients, they have a right to expect that you will honor your professional promise of confidentiality.

Reflection

Go to the code of ethics or other guidelines of your profession and write down what it says about confidentiality.

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

Confidentiality, secrets, and the “need to know”

Developmental theorists tell us that concern about confidentiality begins when a child first experiences a desire to keep or tell secrets. Secrets manifest a developing sense of self as separate from others, and the desire to share secrets is an expression of reaching out for intimate relationships with others. How secrets are handled in those early stages of development can have long-lasting effects on an individual’s sense of security, self-esteem, and success at developing intimacy.4 The power of a secret, or of being in a position to tell a secret, is nowhere conveyed more clearly than when a 2-year-old child has a secret pertaining to someone’s birthday present! When was the last time that you had a secret that was so potent it was difficult, maybe impossible, to keep?

It is not considered a breach of confidentiality if you share “secret” information with other health professionals involved in the patient’s care as long as the information has relevance to their role in the case. In fact, to share it is deemed essential for arriving at a caring response because up-to-date, thorough information is the structure on which high-quality health care delivery to a patient depends.5 Some information comes from your clinical evaluation of the patient’s condition; the rest has to come from the patient.

A reliable general test for who among team members should be given certain types of information is the “need to know” test. Need-to-know information is necessary for one to adequately perform one’s specific job responsibilities. Does he or she need this information to help provide the most caring response to the patient? Sharing of clinical information must occur so that the health care system can effectively care for a patient. Information that passes the need-to-know test must be distinguished from that which a teammate might be interested to know and especially from information that has no bearing on the teammate’s ability to offer optimum care.

Reflection

Susan is a nurse who works in the orthopedic department of a large urban hospital. Her son’s girlfriend was admitted to the medical department of the same hospital for treatment of a staph infection in her right ankle. Susan’s son asks his mom to “look in the computer and find out what is going on with his girlfriend.” What should Susan do?

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

If you answered that Susan should not access her son’s girlfriend’s record, you are correct. Susan is not a health professional on the team caring for this woman, so she does not have a “need to know” the details. She could go to visit the girlfriend in the hospital and offer her support; however, accessing her medical record would be a breach of confidentiality. Any information about a patient should never be passed along to someone not involved in the care of a patient. All patients have a right to privacy.

What if Susan worked in that department and was the nurse assigned to take care of her son’s girlfriend? In this case, Susan would have a “need to know.” If she was assigned to care for the girlfriend, she would need to access the medical record for relevant clinical details. Susan may choose to recuse herself from the case and seek an alternative patient assignment given that she knows the girlfriend; however, this decision would depend on other factors such as the needs of other patients on the unit and staffing. Her need to know still would not warrant her sharing the information with her son.

Keeping confidences

In Chapters 2 and 4, you were introduced to the ideas of caring and the character traits that a health professional should cultivate. Keeping secret information that flows from patient to health professional is not valued as an end in itself but rather as an instrument that serves trust. And the ultimate value that both the keeping of confidences and the subsequent building of trust points to is human dignity.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree