Wholeness of the individual

Timothy L. Kauffman

Introduction

Aging is a wonderful and unique experience. The word ‘wonderful’ should not imply that aging includes only good things, but rather that it is extraordinary and remarkable. Aging starts in the uterus at the time of conception. It represents the passage of time, not pathology. By the age of 1 year, each individual’s uniqueness is evident, and by the age of 5 years the personality is well formed. Multiply the first 5 years of life by 15 and expand the environmental and life experiences, and one of the hallmarks of aging becomes clear – individual uniqueness. No two people age identically. Idiosyncrasy is the norm, and it is important that the healthcare provider looks at the wholeness of the individual geriatric patient as well as the chief presenting complaint or primary diagnosis.

In the healthcare arena of the United States of America today, the wholeness of the patient is compressed into an electronic number taken from the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), with the 10th coding revision being implemented in 2014. Its requisite use for reimbursement often fails to portray the wholeness of the individual patient’s clinical presentation, which typically involves multimorbidity. Over 50% of older persons in the US have three or more chronic conditions (Boyd et al., 2012). Medical care must be given to the whole patient and the record should document that.

The importance of the whole person and multimorbidities is supported by the findings of White et al. (2013). They studied well-functioning persons, 70–79 years old, and measured decline of gait speed over 8 years. The mortality risk was highest among those with the fastest decline of speed. This loss was more likely in older persons with knee pain, muscle weakness, physical inactivity and higher body mass index.

Age alone is a factor to consider; however, chronological age based on date of birth is not always similar to physiological age, which is based on cross-sectional measurements and comparisons with age-estimated or established norms. For example, a specific 70-year-old man may have an aerobic capacity that is similar to that of the average 60-year-old; the older man is said to have a 10-year physiological age advantage. In Chapter 15 there is a photograph of three individuals ranging in age from 60 to 93; it clearly shows differences among the three, although generalizations can be cautiously extrapolated. But far too often such an age span is grouped together as if aging changes are monolithic: they are not. It is not common to compare a 10-year-old with a 43-year-old, which also represents an age span of 33 years. When dealing with a patient who has lived for seven decades or more, the person’s individuality must be acknowledged by providers, administrators and health delivery systems if optimal care is to be rendered.

Various medical models or perspectives

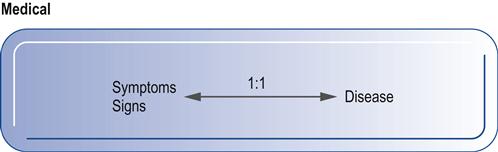

The standard medical model of signs and symptoms equaling a diagnosis of disease does not fit well with the geriatric population (Fig. 1.1). Fried et al. (1991) found that this medical model was able to fit actual cases in fewer than half of the geriatric patients they studied. They developed several other models: the synergistic morbidity model, the attribution model, the causal chain model and the unmasking event model (Fried et al., 1991).

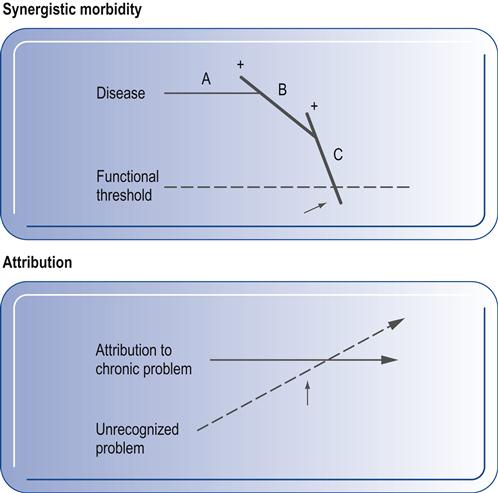

The synergistic morbidity model uses a scenario in which the patient presents with a history of multiple, generally chronic diseases (represented by A, B and C in Fig. 1.2) that result in cumulative morbidity. When this hypothetical patient loses functional capacity, medical attention is sought. This may also be viewed as a cascading effect.

The attribution model uses a scenario in which a patient attributes declining capacity to the worsening of a previously diagnosed chronic health condition (see Fig. 1.2). However, physical examination and workup reveal a new, previously unrecognized condition that is causing the declining health status. This possibility is especially important to consider when evaluating or caring for a patient labeled with a chronic disease such as multiple sclerosis, arthritis or postpolio syndrome. Not all new complaints are attributable to the chronic condition.

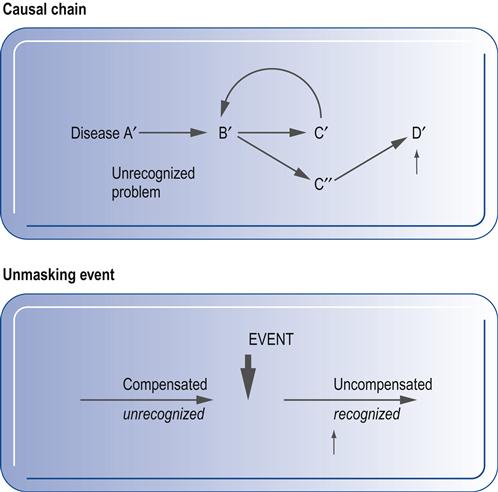

The causal chain model (Fig. 1.3) uses a scenario in which one illness causes another illness and functional decline. In this case, disease A causes disease B, which precipitates a chain of additional conditions that may worsen the present medical problems and/or lead on to further medical problems. For example, a patient who has severe arthritis (Fig. 1.3, disease A’) is unable to maintain good cardiovascular health, which leads to heart disease (disease B’). The cardiac condition leads to peripheral vascular disease (disease C’ and C”), which may reflect back to disease B and/or lead to amputation (disease D’).

The final model is the unmasking event model (see Fig. 1.3). In this situation, a patient has an unrecognized and subclinical or compensated condition. When the compensating factor is lost, the condition becomes apparent and is often viewed as an acute problem. For example, a patient who suffers from vertigo may have functional balance because the visual and proprioceptive systems compensate for the deficient vestibular system. However, when walking on soft carpet or in a darkened room, this individual may have marked balance dysfunction, which may lead to a fracture resulting from a fall.

Coming from a similar perspective, Besdine (1990) presented several important concepts that relate to the complexity of geriatric care in his introduction to the first edition of the Merck Manual of Geriatrics. First, he states that ‘the restriction of independent functional ability is the final common outcome for many disorders in the elderly’. Like Fried et al. (1991) in their attribution and unmasking event models, Besdine warns that ‘deterioration of functional independence in active, previously unimpaired elders is an early subtle sign of untreated illness characterized by the absence of typical symptoms and signs of disease’. Additionally, he suggests that in geriatric medicine there is a ‘poor correlation between type and severity of problem (functional disability) and the disease problem list’. Besdine warns further that finding a diseased organ or diseased tissue does not necessarily determine the degree of functional impairment that will be found. Another lesson he points out is that ‘the severity of illness as measured by objective data does not necessarily determine the presence or severity of functional dependency’.

Recent research validates the need to consider the wholeness of each patient because of the complexity of treating the aging patient. Boyd et al. (2005a) studied clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) as they might apply to a hypothetical 79-year-old woman with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic heart failure, hypertension, stable angina, atrial fibrillation, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes mellitus, osteoarthritis and osteoporosis. They reported that most CPGs did not present modifications for these common geriatric comorbidities. Using the relevant CPGs, this hypothetical woman would have been prescribed 12 medications, with a high cost for the drugs and a risk of adverse drug interactions. In another study, Boyd et al. (2005b) reported that hospitalization for an acute illness in moderately disabled, community-dwelling older women led to increased dependence in daily living activities that persisted for up to 18 months after hospitalization and the resolution of the acute problem. They advocate improved interventions during and after hospitalization.

Because of the uniqueness of each aging patient, these authors advocate an interdisciplinary team approach to effectively treat the common multiple comorbidities. The whole person must be considered and rehabilitation services should be consulted in the majority of geriatric cases.

Aging considerations and rehabilitation

Physical exercise

Exercise, fitness and aging

From a philosophical point of view, one might consider movement to be the most fundamental feature of the animal kingdom in the biological world. Thus, life is movement. Movement is crucial not only for securing basic needs such as food, clothing and shelter but also for obtaining fulfillment of higher psychosocial needs that involve quality of life. Maintaining independence in thought and mobility is a universal desire that is, unfortunately, not achieved by all individuals.

The value of exercise and fitness is that they help to maintain the fullest vigor possible as time ages everyone. By exercising, it is hoped that one may enhance the quality of life, decrease the risk of falls and maintain or improve function in various activities. Fitness, however, is more than aerobic capacity. It is a state of mind and it involves endurance (physical work capacity determined by oxygen consumption, VO2), strength, flexibility, balance, coordination and agility.

The benefits of exercise are systemic and may be viewed as being favorable for all body systems and functions provided the phenomena of overuse are abated before causing irreparable damage to the organism. The opposite is also true; the deleterious effects of hypomobility (less than normal mobility) are profound (see Chapter 56). Box 1.1 presents a number of the beneficial effects of exercise on the actions of various cells, tissues and systems and on the organism as a whole, as judged by comparing the findings with those of sedentary people.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree