Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to determine which preoperative factors might predict the duration of inpatient rehabilitation for total knee arthroplasty (TKA) patients in the absence of complications.

Methods

We included 282 patients who had undergone primary TKA for osteoarthritis. The aim of the rehabilitation program was to recover 90 degrees of active knee flexion and good enough functional status to allow direct discharge to the patient’s home. Patients presenting complications were excluded. The following preoperative parameters were recorded: demographic factors, comorbidity, previous lower limb arthroplasty, the presence of a home help, the pain level (on a visual analogue scale, VAS) and functional scores. The length of stay in the orthopaedic surgery unit was also taken into consideration. Predictive factors for the duration of inpatient rehabilitation were analyzed using univariate and then multivariate linear regression.

Results

In a univariate analysis, the length of stay (24.1 ± 8.1 days) depended on female gender, living alone, the presence of a home help and previous arthroplasty ( p < 0.25). However, when these factors were introduced into a multivariate predictive model, only 2% of the variation in the length of stay was accounted for.

Conclusion

The duration of inpatient rehabilitation for TKA patients in the absence of complications cannot be statistically modelled from the preoperative parameters studied here.

Résumé

Objectif

Le but de cette étude a été de déterminer quels facteurs étaient capables de prédire la durée d’hospitalisation en rééducation des patients opérés d’une prothèse totale de genou non compliquée.

Méthode

Deux cent quatre-vingt-deux patients qui ont bénéficié d’une prothèse totale de genou de première intention pour gonarthrose primitive ont été inclus. L’objectif du programme de rééducation était de récupérer 90 degrés de flexion active de genou et un bon état fonctionnel autorisant un retour directement à domicile. Les patients qui ont présenté des complications ont été exclus. Les facteurs démographiques, les comorbidités, les antécédents de prothèses de membre inférieur, la présence d’une aide ménagère, le vécu douloureux (EVA) et les facteurs fonctionnels ont été analysés avant la chirurgie. La durée de séjour en unité chirurgicale d’orthopédie a été prise en considération. La durée de séjour en hospitalisation pour rééducation dans un centre hospitalier régional non universitaire a été analysée afin de déterminer les facteurs de prédiction selon une régression linéaire univariée puis selon une analyse multivariée.

Résultats

La durée de séjour (24,1 ± 8,1 jours) dépend du sexe féminin, du fait de vivre seul, de la présence d’une aide ménagère et des antécédents de prothèse ( p < 0,25). Quand ces facteurs sont introduits afin d’établir le modèle prédictif en utilisant une analyse multivariée, seulement 2 % de la variation de la durée de séjour est expliquée.

Conclusion

La durée de séjour en hospitalisation pour rééducation après prothèse totale du genou non compliquée ne peut pas être modélisée statistiquement à partir des paramètres préopératoires étudiés.

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

Osteoarthritis represents the most frequent reason for performing total knee arthroplasty (TKA). At the outset, invalidating pain is treated with drugs and physiotherapy but the latter do not halt destruction of the knee joint. Hence, TKA is prescribed when the osteoarthritis is no longer controlled by medication or physical techniques and when functional activities (such as walking) are severely impaired . However, TKA can be a high-risk operation which may justify hospitalization of the subject in a rehabilitation service in order to achieve the best possible functional outcome . The TKA outcome is usually good to excellent, with less pain, improved functional abilities and better quality of life . Total knee arthroplasty patients show good longevity; the survival rate after 10 years is over 90% .

After TKA, rehabilitation care begins in the orthopaedic surgery service and continues (in most cases) with hospitalisation in an inpatient rehabilitation service or (less frequently) in a day hospital or even directly at home. Recently, Oldmeadow et al. developed and validated (in Australia) a method for predicting extended inpatient rehabilitation after hip and knee arthroplasty . The Risk Assessment and Predictor Tool (RATP) identifies three risk levels, with a correct discharge prediction rate of 74.6%. When the RATP score is below 6, hospitalization is predicted; when the score is over 9, home discharge is predicted. However, this score is not used in many other countries, where operated TKA patients are sent to a rehabilitation centre (although there are some exceptions). In fact, the discharge destination for TKA patients depends on several factors, such as age, comorbidities, postoperative functional ability, the availability of home help, the surgeon’s habits and the patient’s wishes . In France, a patient’s wishes are taken into account but do not prevail over the medical team’s discharge decision. Only a few studies have determined which factors contribute to rehabilitation hospitalisation and have focused on the length of stay; however, these were primarily health economic evaluations and did not consider the functional results on discharge from the rehabilitation centre . The objective of the present study was to collate the preoperative factors which may determine the duration of inpatient rehabilitation by taking into account the results of rehabilitation care (defined as 90 degrees of active knee flexion and a functional status allowing direct home discharge).

1.2

Method

1.2.1

Population

We included all patients admitted to our rehabilitation service following primary TKA for osteoarthritis between January 2004 and June 2007. Fifty-one percent of the patients had been operated on in a public hospital, whereas the remainder came from four different private clinics. Indications such as arthritis, bone tumours, fractures, osteonecrosis and TKA revisions were excluded. All the information was collected by the same physical medicine and rehabilitation specialist when the patients were admitted to the rehabilitation service. This information (noted in the patient’s medical files) included demographic data, functional abilities, the presence of home help prior to surgery and the presence of complications before or during rehabilitation. Next, the information was extracted retrospectively into a computer database (SPSS version 14.0 from SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data on 305 patients was compiled; 23 individuals were excluded from the study, due to lack of data. Patients were then referred to a hospital rehabilitation service that specialized in bone and joint diseases. After rehabilitation care, all patients were directly discharged to their home.

1.2.2

Rehabilitation management

During hospitalization in the orthopaedic service, patients underwent physical medicine therapy for an hour a day, consisting of the application of ice, physiotherapy to improve joint amplitude and training in transfers and displacement with a knee batch and crutches, depending on the patient’s ability. The patient’s state of health had to stabilize before transfer to the rehabilitation service.

During hospitalization in the rehabilitation service, the patients underwent twice-daily, 1-hour physical medicine and rehabilitation sessions on five days of the week. The session consisted in increasing the amplitude of knee joint flexion, practising transfers, walking and activities of daily living (such as getting dressed and washing), implementing therapeutic changes related to comorbidities, administering preventive treatments for thrombosis/phlebitis (low molecular weight heparin, support stockings and early mobilization) and, lastly, providing medical information on how to avoiding infections and the need to revise the prosthesis. Home discharge was decided by the same physical medicine and rehabilitation specialist, on the basis of three criteria which have since been partly incorporated into guidelines issued by France’s High Authority for Health (Haute Autorité de santé) :

- •

firstly, the patient had to be independent with respect to the activities of daily living; if this was not the case, home help was arranged;

- •

secondly, the patient had to be capable of walking well-enough to reduce the risk of falls, as evaluated by the ability to maintain a unipedal stance (on the operated side) for more than 5 s, according to the test described by Hurvitz et al. . In the event of failure, crutches were prescribed;

- •

thirdly, the joint amplitude for active knee flexion had to be at least 90 degrees (measured manually with a goniometer).

At the time of home discharge, the rehabilitation programme’s results were evaluated in terms of the amplitude of active knee flexion, the walking distance and the International Knee Society (IKS) function score (Appendix 1) .

1.2.3

Factors studied

Demographic data (age, gender and cohabitational status) were compiled retrospectively for 282 patients admitted to the rehabilitation service over the period from 2004 to 2007. The presence of a home help, the pain level (VAS: ≤ 6 or > 6) and functional status – based on the walking distance (< 200 m; 200 to 400 m; > 400 m, with respect to the RATP score) and the use of gait aids (cane or crutches) – were evaluated prior to surgery. The presurgery IKS function score (0 to 100 points) and the Lequesne index (≤ 12 or > 12 points) were reported prospectively (Appendix 2) . The length of stay in the orthopaedic service was also taken into consideration, as were personal medical histories related to lower limb prostheses (presence or absence) and any associated diseases (presence or absence) that had required regular therapeutic changes (such as diabetes, hypertension and pulmonary, cardiac or psychiatric diseases). After hospitalization for rehabilitation, we recorded active knee flexion, the walking distance, the IKS function score and the presence or absence of complications (venous thromboses with or without pulmonary embolism, acute infections of the TKA, mobilization of the prosthesis under general anaesthesia, poor skin closure that required a surgeon’s opinion and acute cardiac, pulmonary or digestive decompensation. Any patients presenting one or more of the above-mentioned complications and requiring transfer to another medical or surgical service were excluded from our analysis.

1.2.4

Statistical analysis

The number of days of inpatient rehabilitation (from admission to discharge) was expressed as the mean ± standard deviation [range]. Chronological bias related to the length of the study was measured with a single-factor analysis of variance (ANOVA). The results of the rehabilitation programme were described at discharge. The preoperative IKS and Lequesne scores were studied separately and were not used in the predictive model because they included several parameters that had already been studied.

The predictive model was built for complication-free TKA patients. The variables studied were first analyzed in a univariate analysis. Redundancy between variables was determined in correlation and colinearity analyses. Parameters with a p value below 0.25 were then introduced into a multiple linear regression model. The model was validated at p < 0.05 after analysis of the regression and the residuals.

1.3

Results

After exclusion of 38 patients having presented complications, a cohort of 244 TKA patients was described in terms of demographic parameters, preoperative functional ability and the presence or absence of a joint prosthesis or comorbidities ( Tables 1 and 2 ). On average, patients were admitted to the rehabilitation service 7.5 ± 1.7 days after surgery.

| Age (years) | 71.4 ± 8.7 [46–87] |

| Gender | |

| Male n (%) | 97 (39.8%) |

| Female n (%) | 147 (60.2%) |

| Living alone n (%) | 101 (41.4%) |

| Home help n (%) | 31 (12.7%) |

| Comorbidities n (%) | 53 (22.6%) |

| No previous lower-limb arthroplasty n (%) | 157 (64.3%) |

| Walking distance | |

| < 200 m | 85 (34.8%) |

| 200–400 m | 40 (16.4%) |

| > 400 m | 119 (48.8%) |

| Gait assistance | |

| None | 142 (58.4%) |

| Cane | 82 (33.7%) |

| Crutches | 19 (7.8%) |

| Pain level (VAS) | 6.3 ± 1.9 [0–10] |

| IKS function score (out of 100 pts) | 35.7 ± 17 [0–80] |

| Lequesne index (out of 24 pts) | 11.4 ± 3.1 [4–19] |

| Time in the surgical ward (d) | 7.5 ± 1.7 [3–17] |

| Complications | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Venous thrombosis | 21 (7.4%) |

| Poor skin closure | 8 (2.8%) |

| Manipulation under general anaesthesia | 7 (2.4%) |

| Acute TKA infection | 3 (1%) |

| Acute pulmonary decompensation | 3 (1%) |

| Acute cardiac decompensation | 1 (0.3%) |

| Acute digestive decompensation | 2 (0.6%) |

| > 1 complication | 7 (2.4%) |

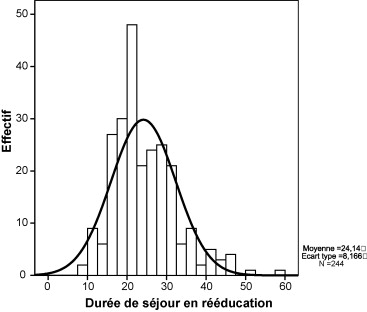

The duration of inpatient rehabilitation was 24.1 ± 8.1 [9–59] days and is presented as a histogram in Fig. 1 . The length of stay was similar in 2004 and 2007 ( F : 0.43; p : 0.72). On discharge from the rehabilitation service, active knee flexion was 97 ± 12 degrees, the walking distance was 369 ± 185 metres and the IKS function score was 48 ± 16 points.

After the univariate analysis, a linear relationship was found for only four preoperative factors: female gender, living alone, the presence of a home help and previous lower limb arthroplasty ( p < 0.25) ( Table 3 ). There was a significant interaction between living alone and female gender ( r : 0.309, p < 0.01) and between living alone and the presence of a home help ( r : −0.213; p < 0.05). This redundancy was confirmed in a colinearity analysis (tolerance > 3) and so the “living alone” parameter was excluded from the predictive model. We did not observe an interaction between female gender and the presence of a home help ( r : 0.024; p > 0.05). The “previous lower-limb arthroplasty” parameter was independent of the others ( Table 4 ). Neither patient’s age nor the length of stay in the orthopaedic service influenced the length of stay in the rehabilitation service. There were no relationships between the IKS function score, the Lequesne index and the length of stay in the rehabilitation service ( F : 0.02; p : 0.87 and F : 0.01; p : 0.90, respectively).

| Parameters | Duration of stay (days) | Coefficient of regression | F (1,244) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age ( n = 244) (71.4 ± 8.1 years) | 24.1 ± 8.1 | −0.10 | 0.02 | 0.87 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male ( n = 97) | 22.8 ± 8.2 | 0.153 | 4.12 | 0.04 |

| Female ( n = 147) | 25.0 ± 7.9 | |||

| Living alone | ||||

| No ( n = 143) | 23.1 ± 8.2 | 0.190 | 4.85 | 0.02 |

| Yes ( n = 101) | 25.6 ± 7.9 | |||

| Home help | ||||

| No ( n = 213) | 25.6 ± 8.7 | −0.053 | 4.16 | 0.04 |

| Yes ( n = 31) | 24.1 ± 8.1 | |||

| Previous leg arthroplasty | ||||

| No ( n = 157) | 24.6 ± 8.2 | −0.089 | 1.61 | 0.20 |

| Yes ( n = 87) | 23.2 ± 8 | |||

| Comorbidities | ||||

| No ( n = 191) | 23.8 ± 9.4 | 0.052 | 0.57 | 0.44 |

| Yes ( n = 53) | 25.2 ± 7.8 | |||

| Walking distance before surgery | ||||

| < 200 m ( n = 85) | 24.1 ± 6.9 | −0.097 | 0.25 | 0.61 |

| 200–400 m ( n = 40) | 25.4 ± 8.9 | |||

| > 400 m ( n = 119) | 23.4 ± 9.3 | |||

| Gait assistance before surgery | ||||

| No ( n = 142) | 23.7 ± 8.1 | −0.078 | 0.77 | 0.38 |

| Yes ( n = 102) | 24.6 ± 8.2 | |||

| Pain level | ||||

| VAS score ≤6 ( n = 119) | 24.8 ± 7.9 | −0.062 | 0.68 | 0.40 |

| VAS score >6 ( n = 125) | 23.9 ± 8 | |||

| Stay in the surgical ward ( n = 244) (7.5 ± 1.7 days) | 24.1 ± 8.1 | 0.060 | 0.48 | 0.34 |

| IKS function score ( n = 244) (35 ± 17.5 points) | 24.1 ± 8.1 | 0.10 | 0.02 | 0.87 |

| Lequesne index 12 ( n = 145) | 24.2 ± 8.8 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.77 |

| > 12 ( n = 99) | 24.5 ± 6.9 | |||

| Coefficient | Gender | Living alone | Home help | Previous arthroplasty | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation | Gender | 1 | −0.321** | −0.102 | −0.50 |

| Living alone | −0.321** | 1 | 0.241* | 0.090 | |

| Home help | −0.102 | 0.241* | 1 | 0.135 | |

| Previous arthroplasty | −0.50 | 0.090 | 0.135 | 1 |

The multivariate linear regression analysis had low predictive power and included only female gender, the presence of a home help and previous lower limb arthroplasty ( r : 0.181; adjusted r 2 : 0.02; standard error: 8.11) ( Table 5 ). The r 2 value was 0.02, which means that only 2% of the variability in the duration of inpatient rehabilitation was accounted for by the predictive model. Hence, this model is not of use when observing a group of TKA patients and is not accurate enough to predict the outcome for a given patient ( p < 0.049).

| Predictive model | B coefficient (not standardized) | Standard error | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 26.5 | 4.23 | 6.25 | 0.0001 |

| Gender | 2.36 | 1.08 | 2.19 | 0.02 |

| Home help | −1.89 | 1.79 | −1.05 | 0.29 |

| Previous arthroplasty | −1.78 | 1.11 | −1.60 | 0.11 |

| ANOVA | Type III sum of the squares | Degrees of freedom | Mean squares | F (3,244) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression | 520 | 3 | 173 | 2.63 | 0.049 |

| Residuals | 15,280 | 241 | 65 | ||

| Total | 15,800 | 244 | |||

1.4

Discussion

France’s High Authority for Health is currently promoting a decrease in the length of hospitalization and is encouraging home care. However, this reasoning must not decrease the quality of care and must take account of a patient’s social and economic status, as well as opportunities for outpatient rehabilitation . Our study sought to address the factors influencing the length of stay in a rehabilitation hospital, while considering the functional outcome of the rehabilitation care. The latter was defined as (a) the provision of a home help, (b) improvement in gait (with or without an assistive device) for minimizing the risk of falls and (c) active knee flexion of over 90 degrees on discharge. According to certain authors, the recovery of a stable medical state and functional ability is enough for home discharge ; however, we consider that active knee flexion of over 90 degrees is essential for home discharge, since some knee mobility is required after a TKA . The role of the kinesitherapy is thus to help the patients rapidly recover independent movement and transfer capacities and enough knee mobility to allow home discharge. Only Lin et al. have reported on the percentage of TKA patients able to bend their knee by more than 70 degrees . On discharge from the rehabilitation centre, only 74% of the study population had achieved this target, which corresponds to a rather poor result. In fact, this parameter is of great value because flexion of more than 90 degrees corresponds to a better functional result and enables greater independence (a more comfortable sitting position, easier transfers and use of stairs and the ability to step over an obstacle) . This factor accounts for the mean duration of inpatient rehabilitation of 24 days in our study, relative to the value of 11 days described by Lin et al. . However, the latter study focused on the length of stay in the rehabilitation hospital and did not taking into account the patients’ destinations on discharge – not all returned home directly, in contrast with our study population. Lin et al. explained the length of stay in the rehabilitation service in terms of age (over 80), male gender, black race, living alone, comorbidities and the presence of a TKA or total hip arthroplasty (THA) . However, the predictive model was very imprecise because it accounted for only 10% of the variability in the length of stay ( r 2 : 0.10). Our study population was not the same because only Caucasian TKA patients were included. Furthermore, the two studies differed in terms of the post-TKA rehabilitation care; our objective was to recover good knee flexion and good functional status.

In our univariate analysis, four explanatory parameters (female gender, living alone, the presence of a home help and previous lower-limb arthroplasty) presented a significant linear relationship with the length of stay in the rehabilitation service. We were not surprised to note that the “living alone” parameter was specifically related to the need for a home help. The time needed during hospitalization to arrange a home help for those patients who required one after surgery could explain the inverse relationship and thus why the length of stay was an average of 1.5 days longer (representing an additional cost of 6%, i.e. 1.5 days relative to 24 days). This inverse relationship explains why the “living alone” factor was excluded from the predictive model.

We also identified an inverse relationship between previous lower-limb arthroplasty and the length of stay. By virtue reason of their prior experience of lower-limb arthroplasty, these patients may have benefited more from the rehabilitation programme, to the extent that their stay in the rehabilitation service was 1.5 days shorter, on average.

Various authors have shown a correlation between comorbidities (such as diabetes) and the length of stay required for rehabilitation . Our analysis may not have been precise enough for comorbidities to exert an influence. In our experience, daily treatment of diabetes (in the absence of other complications) does not result in an increase in the length of hospitalization. In contrast, we voluntarily excluded all acute complications from our study because the management of these patients could have increased the length of hospitalization. In these cases, the patients had to return to a surgical department or transfer to other medical services. In fact, our method distinguished between comorbidities with no impact on care management from those that do have an impact.

In the absence of post-TKA complications, the length of stay in the orthopaedic service did not influence the length of stay in the rehabilitation service. The preoperative walking distance, functional status and Lequesne index did not significantly influence the predictive model – despite the fact that a Lequesne index of over 12 is generally used to justify a TKA . The efficacy of the prosthetic surgery and the rehabilitation programme could explain this result because the patient’s state of health improved independently of the consequences of the osteoarthritis, as suggested by the rise in the IKS functional score from 35 to 48 points . However, this relatively low final score of 48 shows that our discharge criteria were not very severe in terms of knee flexion, walking ability and independence in the activities of daily living. Stricter criteria (taking into account knee extension, quadriceps strength and walking distance in the absence of gait aids or a helper) would perhaps have enabled better prediction. The patient’s pain level probably failed to have any effect, for the same reason. Hospitalization in a rehabilitation service can perhaps have a positive psychological effect on the patient, due to provision of support by the medical team.

1.5

Conclusion

Only 2% of the variability in the length of hospitalization for post-TKA rehabilitation is accounted for by female gender, the presence of a home help and previous lower-limb arthroplasty, when considering the results of the rehabilitation care and in the absence of complications. The predictive model is thus very limited and it was not possible to predict the length of post-TKA inpatient rehabilitation from the preoperative parameters studied here.

From an economic point of view, the potential for decreasing the length of stay in the rehabilitation service may depend specifically on the quality of the rehabilitation care in terms of improved knee flexion and the patient’s functional state. Arrangement of a home help led to a extra 1.5 days of hospitalization, i.e. a 6% increase in the cost of the hospital stay.

Appendix 1: the IKS function score

| Walking distance | |

| Unlimited | 50 pts |

| > 1000 m | 40 pts |

| 500 to 1000 m | 30 pts |

| < 500 m | 20 pts |

| Housebound | 10 pts |

| Unable | 0 pts |

| Stairs | |

| Normal up & down | 50 pts |

| Normal up, down with rail | 40 pts |

| Up & down with rail | 30 pts |

| Up with rail, unable down | 15 pts |

| Unable | 0 pts |

| Functional deductions | |

| No cane | 0 pts |

| Cane | −5 pts |

| Two canes | −10 pts |

| Crutches or walker | −20 pts |

Appendix 2: the Lequesne index of severity for osteoarthritis of the knee

| Pain or discomfort during nocturnal bed rest | None | 0 Points |

| Only on movement or in certain positions | 1 | |

| Even without movement | 2 | |

| Duration of morning stiffness or pain after getting up | < 1 min | 0 |

| 1 to 15 min | 1 | |

| > 15 min | 2 | |

| Remaining standing for 30 min increases pain | No | 0 |

| Yes | 1 | |

| Pain on walking | No | 0 |

| Only after a certain distance | 1 | |

| Very rapidly and increasing | 2 | |

| Pain or discomfort after getting up from sitting without use of arms | No | 0 |

| Yes | 1 | |

| Maximum distance walked | Unlimited | 0 |

| >1 km but limited | 1 | |

| About 1 km (about 15 min) | 2 | |

| About 500 to 900 m | 3 | |

| From 300–500 m | 4 | |

| From 100–300 m | 5 | |

| < 100 m | 6 | |

| Walking aids required | 1 walking stick or crutch | +1 |

| 2 walking sticks or crutches | +2 | |

| Difficulties in daily living | Up a standard flight of stairs | 0–2 |

| 0: easily | Down a standard flight of stairs | 0–2 |

| 0.5, 1 or 1.5 for mild, moderate or marked difficulty | Able to squat or bend at the knee | 0–2 |

| 2: impossible | Able to walk on uneven ground | 0–2 |

2

Version française

2.1

Introduction

La gonarthrose représente la maladie du genou la plus fréquente pour être à l’origine de la mise en place d’une prothèse totale de genou (PTG). Au début, les douleurs invalidantes sont traitées par des médicaments et des traitements physiques qui ne sont cependant pas capables de stopper la destruction de l’articulation du genou. La PTG est alors proposée quand la gonarthrose échappe au traitement médical et quand les activités fonctionnelles, telle la marche, sont altérées . La mise en place d’une PTG représente une chirurgie à risque qui peut justifier d’hospitaliser les patients en service de rééducation afin d’atteindre le meilleur résultat fonctionnel possible . Les résultats des PTG sont bons à excellents avec diminution des douleurs, amélioration des capacités fonctionnelles et de la qualité de vie . La longévité des PTG est bonne et dépasse 90 % de survie à dix ans .

Après chirurgie pour PTG, les soins de rééducation débutent dans le service de chirurgie orthopédique et se poursuivent dans la majorité des cas en hospitalisation pour rééducation ou moins fréquemment en hospitalisation de jour ou en externat directement à domicile. Récemment, Oldmeadow et al. ont développé et validé, en Australie, une méthode pour prédire les besoins d’hospitalisation en rééducation des patients après prothèse de hanche et de genou . Le score du Risk Assessment and Predictor Tool (RATP) identifie trois niveaux de risque avec une pertinence de 74,6 %. Quand le score RATP est inférieur à 6, la prédiction est d’hospitaliser et quand le score est supérieur à 9, la prédiction est un retour directement à domicile. Ce score n’est habituellement pas utilisé dans d’autres pays où les patients opérés d’une PTG sont adressés en centre de rééducation, même si cela ne correspond pas à une règle absolue. En fait, l’orientation des patients porteurs d’une PTG dépend de plusieurs facteurs comme l’âge, les comorbidités, les possibilités fonctionnelles postopératoires, les possibilités d’aide, les habitudes du chirurgien et les souhaits du patient . En France, le souhait du patient correspond à un critère d’aide à la décision mais n’est pas opposable au patient. Seules quelques études ont déterminé quels facteurs contribuaient à l’hospitalisation en rééducation en se focalisant sur la durée de séjour dans un but médicoéconomique sans prendre en considération les résultats fonctionnels à la sortie du centre de rééducation . L’objectif de cette étude a été de colliger les facteurs préopératoires qui ont déterminé la durée de séjour en hospitalisation pour rééducation en tenant compte des résultats des soins de rééducation définis par l’obtention d’une flexion active de genou de 90 degrés et d’un statut fonctionnel autorisant un retour directement à domicile.

2.2

Méthode

2.2.1

Population

Tous les patients admis en hospitalisation pour rééducation après PTG de première intention pour gonarthrose entre janvier 2004 et juin 2007 ont été inclus. Cinquante et un pour cent des patients avaient été opérés à l’hôpital public alors que les autres patients provenaient de quatre cliniques privées différentes. Les indications de prothèse de genou comme l’arthrite, la tumeur osseuse, la fracture, l’ostéonécrose et les révisions de PTG ont été exclues. Toutes les informations ont été collectées par le même médecin de médecine physique et réadaptation à l’entrée des patients dans le service de rééducation. Ces informations, qui ont été écrites dans le dossier du patient, ont rapporté les informations démographiques, les capacités fonctionnelles, la présence d’une aide ménagère en préopératoire et les complications avant et durant l’hospitalisation en rééducation. Ces informations ont ensuite été extraites rétrospectivement sur une base statistique de données informatisées SPSS 14.0 (Chicago, IL, États-Unis). Les données de 305 patients ont été compilées et 23 ont été exclues de l’étude en raison du manque d’informations. Les patients étaient ensuite adressés dans le même service hospitalier de rééducation spécialisé en pathologies ostéoarticulaires. Après les soins de rééducation, tous les patients sont rentrés directement à leur domicile.

2.2.2

Prise en charge de rééducation

Durant l’hospitalisation en service d’orthopédie, les patients ont bénéficié d’un traitement de médecine physique d’une heure par jour, qui a consisté en l’application de glace, l’utilisation d’un arthromoteur en gain d’amplitude articulaire, l’entraînement physique aux transferts et aux déplacements avec attelle de genou et cannes anglaises adaptées aux capacités du patient. Les patients devaient présenter un état de santé stable avant leur transfert dans le service pour rééducation.

Durant l’hospitalisation en rééducation, les patients ont bénéficié de deux fois une heure par jour, cinq jours sur sept, d’un traitement de médecine physique et de réadaptation. Le programme a consisté en l’augmentation des amplitudes articulaires du genou, la réalisation du travail des transferts et de la marche, la réadaptation aux activités de la vie quotidienne comme l’habillage et la toilette, la mise en place des adaptations thérapeutiques liées aux comorbidités et des traitements de prévention de la thrombose-phlébite (héparine de bas poids moléculaire, bas de contention et mobilisation précoce) et enfin, en l’éducation thérapeutique des sujets porteurs d’une PTG contre l’infection et la révision précoce de la prothèse. La décision de sortie à domicile a été déterminée par le même médecin de médecine physique et de réadaptation selon trois arguments qui depuis ont été en partie repris par les recommandations professionnelles de la Haute Autorité de santé :

- •

premièrement, le patient devait être indépendant pour les actes de la vie quotidienne. Une aide ménagère était mise en place dans le cas contraire ;

- •

deuxièmement, le patient devait avoir retrouvé une capacité de marche suffisante sans risque de chute évalué par le possibilité de maintien durant cinq secondes d’un appui monopodal du côté du genou opéré selon le test de Hurvitz et al. . En cas d’échec à ce test, des cannes étaient prescrites ;

- •

troisièmement, l’amplitude articulaire devait atteindre 90 degrés de flexion active du genou prothésé selon la mesure manuelle à l’aide d’un goniomètre.

Les résultats du programme de rééducation ont été évalués à la sortie au domicile par l’amplitude active de flexion du genou, le périmètre de marche et la partie fonctionnelle du score de l’International Knee Society (IKSS) (Annexe 1) .

2.2.3

Facteurs étudiés

Les variables ont été compilées rétrospectivement chez 282 patients admis entre l’année 2004 et 2007 en hospitalisation pour rééducation. Ces variables ont été représentées par des facteurs démographiques : âge, sexe, vie seule. La présence d’une aide ménagère, le vécu douloureux (EVA : ≤ 6 or > 6) et le statut fonctionnel à partir du périmètre de marche (< 200 m ; 200 à 400 m ; > 400 m en référence au score RATP) et des aides techniques (absence de canne ou cannes anglaises) ont été évalués avant chirurgie. La partie fonctionnelle du score IKS (0 à 100 points) et le score de Lequesne (≤ 12 ou > 12 points) avant chirurgie ont été reportés prospectivement (Annexe 2) . La durée de séjour dans le service d’orthopédie a été prise en considération. Les antécédents de prothèses des membres inférieurs (présence ou absence) et les antécédents de maladies associées (présence ou absence) qui ont requis des adaptations thérapeutiques régulières, comme pour le diabète, l’hypertension, les maladies pulmonaires, cardiaques ou psychiatriques ont été considérés. Après hospitalisation pour rééducation, la flexion active du genou, le périmètre de marche, la partie fonctionnelle du score IKS et les complications (thromboses veineuses avec ou sans embolie pulmonaire, les infections aiguës de la PTG, les mobilisations de la prothèse sous anesthésie générale, les désunions cicatricielles qui ont nécessité un avis chirurgical et les décompensations aiguës cardiaques, pulmonaires et digestives ont été mentionnés. Les patients qui ont présenté une complication précitée et qui ont nécessité un transfert dans un autre service médical ou chirurgical ont été exclus de l’analyse.

2.2.4

Analyse statistique

La durée de séjour en hospitalisation pour rééducation a été exprimée selon la moyenne et l’écart-type en nombre de jours de l’admission à la sortie. Le biais chronologique lié à la durée de l’étude a été mesuré avec une analyse de variance à un facteur (Anova). Les résultats du programme de rééducation ont été décrits à la sortie. Les deux scores de l’IKS et de Lequesne avant chirurgie ont été étudiés à part et n’ont pas été utilisés dans le modèle prédictif car ils incluaient plusieurs paramètres déjà étudiés.

Le modèle prédictif a été recherché en l’absence de complication. Les variables étudiées ont tout d’abord été analysées selon une analyse univariée et la redondance entre les variables a été déterminée en utilisant une analyse de corrélations et de colinéarités. Les facteurs significatifs ont ensuite été introduits dans le modèle de régression linéaire multiple si la valeur de p était inférieure à 0,25. Le modèle a été validé pour la valeur p < 0,05 après analyse de régression et des résidus.

2.3

Résultats

Après sortie de l’étude de 38 patients qui ont présenté des complications, une cohorte de 244 patients opéré du genou a été caractérisée par les paramètres démographiques, les capacités fonctionnelles avant chirurgie, la présence ou non d’antécédent de comorbidités ou de prothèse articulaire ( Tableaux 1 et 2 ). Les patients ont été admis en hospitalisation pour rééducation en moyenne à 7,5 ± 1,7 jours de la chirurgie.