22 Vessels of the thyroid

22.2 Anatomy and physiology

22.2.1 Thyroid gland

Shape and dimensions

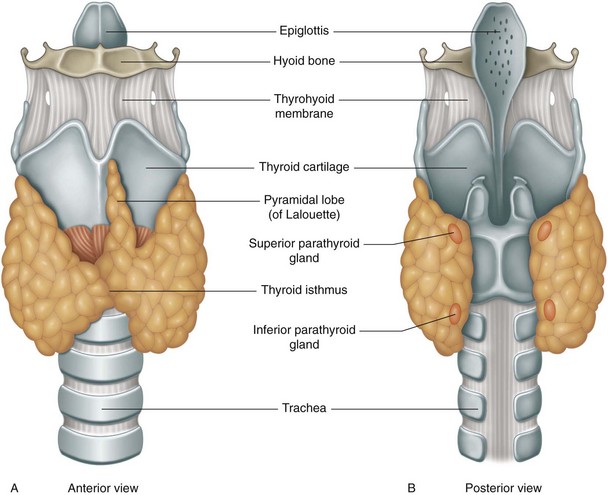

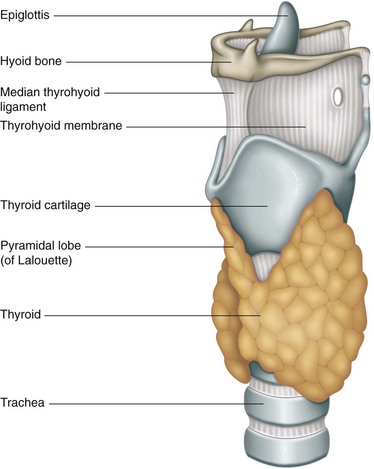

In the frontal plane the thyroid is shaped like an H or a butterfly (Fig. 22.1). In the transverse plane it has the form of a horseshoe, concave posteriorly and enclosing the trachea. The right and left lobes are approximately conical and connected by a narrow medial isthmus.

Frequently larger in women than in men, the lobes generally measure:

Stability

• posteriorly by the visceral sheath medially and the carotid sheath laterally

• anteriorly by the pretracheal layer of the deep cervical fascia, which also surrounds the infrahyoid strap muscles.

The pretracheal lamina inserts on the inferior border of the hyoid bone and splits into two layers:

Physiology

Thyroxine and triiodothyronine

T3 and T4 are necessary for normal growth and development, especially of the skeleton and nervous system. Virtually all organs and systems in the body are influenced by thyroid hormones. The physiological effects of T3 and T4 on the heart, skeletal muscles, skin, digestive and reproductive systems are more marked when the thyroid gland is hyperactive or hypoactive. These modifications and related dysfunctions are detailed in Table 22.1.

Table 22.1 Symptoms of thyroid dysfunction

| Hyperthyroid | Hypothyroid |

|---|---|

| Symptoms | |

| Sympathicotonia | Fatigue, lethargy |

| Nervousness | Apathy, sleepiness |

| Irritability, intense emotion | Memory problems, poor hearing |

| Peripheral neuropathy, carpal tunnel syndrome | |

| Excessive sweating, thirst | Hypothermia, chills |

| Intolerance to heat | Intolerance to cold |

| Palpitations | |

| Frequent stools, diarrhea | Constipation |

| Weak muscles, fatigue | Muscle cramps, myotonia |

| Trembling | Arthralgia, paresthesia |

| Oligomenorrhea, amenorrhea | |

| Weight loss despite increased appetite | Weight gain despite decreased appetite |

| Signs | |

| Tachycardia | Bradycardia |

| Increased systolic and diminished diastolic pressure | Decreased systolic and increased diastolic pressure |

| Leucopenia, thrombopenia | Anemia |

| Hot, smooth, moist skin | Dry, rough, cold skin |

| Trembling, proximal muscle weakness | Edema (nonpitting) |

| Basedow’s disease: ocular signs (fixed gaze, oculopalpebral asynergy, exopthalmia) | Dull hair, fragile nails, hair loss |

| Swelling of the face, hands, and feet; puffiness around the eyes | |

22.3 Clinical examination of the thyroid

22.3.1 Approach to thyroid morphology

Inspection

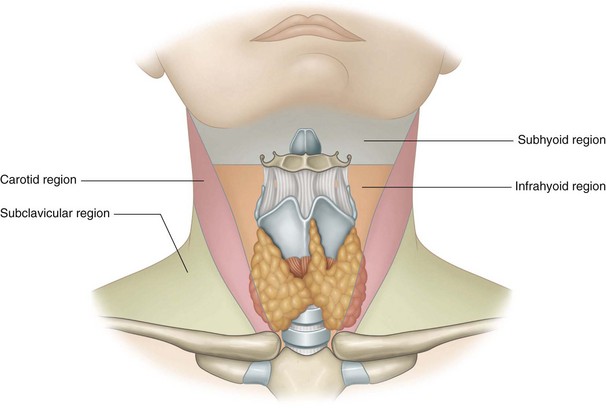

The thyroid is sometimes visible even in the absence of pathology. In subjects with elongated graceful necks, the isthmus region can be clearly seen. Sometimes the thyroid can be noticed casually in profile, as a discrete anterior cervical bulge that moves with swallowing (Fig. 22.2).

Palpation

You might want to provide a glass of water for the patient if he or she needs to swallow repeatedly.

To palpate the isthmus from the sternal notch, glide your fingers upwards using a light touch, and short back and forth movements. Your fingers will run into the substance of the isthmus. Have the patient swallow and feel the elastic isthmus elevate under your finger (Fig. 22.3).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree