Vertebral Compression Fractures

Eileen A. Crawford

Nader M. Hebela

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The World Health Organization defines osteoporosis as bone mineral density (BMD) 2.5 standard deviations below the average BMD of a young adult using dual energy x-ray absorptiometry. Fragility fractures are the primary clinical problem associated with osteoporosis. Vertebral compression fractures (VCFs) are the most common type of fragility fractures in the elderly population with an incidence of approximately 700,000 per year in the United States. Risk factors for osteoporosis-related insufficiency fractures include older age (particularly postmenopausal), female gender, low BMD, a sedentary lifestyle, and a history of fragility fractures.

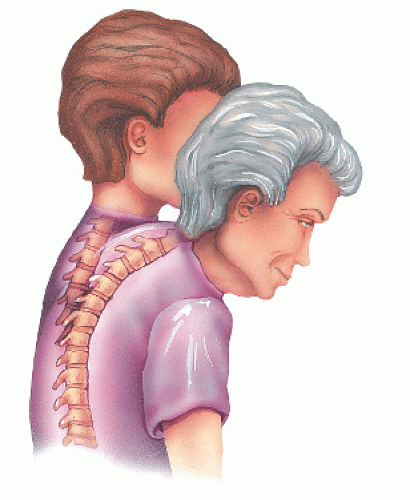

Anatomically, the most common site for VCFs is the thoracic spine where compression of the anterior vertebral body is more likely due to the normal thoracic kyphosis. With progressive collapse of the fractured vertebra, the kyphosis becomes even more pronounced, which may leave the patient more prone to additional fractures.1 The upper lumbar and lower lumbar spine, respectively, are the next most common regions for VCFs.

Osteoporotic VCFs are often asymptomatic at presentation and may be incidental findings on routine chest radiographs. When symptomatic, patients primarily complain of back pain with an onset correlating with a relatively atraumatic event such as bending, standing from a seated position, or lifting a heavy object. The pain may last for several weeks or months. Activity and weight bearing tend to exacerbate the pain, whereas lying down provides relief. Chronic pain may develop due to incomplete healing of the fracture, formation of a pseudarthrosis, or abnormal spine kinematics caused by the deformity.1

Thoracic or lumbar spine pain is the predominant presenting symptom, and neurologic symptoms are infrequent. In cases of thoracic compression fractures with nerve root impingement, patients may report pain radiating anteriorly along the costal distribution of the affected spinal nerve. Spinal cord compression is rare and should suggest a more ominous diagnosis such as tumor or infection. Patients should be asked about constitutional symptoms to assess for these processes.

CLINICAL POINTS

Osteoporosis-related VCFs are most common in postmenopausal Caucasian women who lead a sedentary lifestyle.

A history of prior VCFs significantly increases the risk for future VCFs.

The thoracic spine is the most common location of VCFs.

The primary symptom of VCFs is activity-related back pain, usually without a history of significant trauma.

PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Aside from back pain in the affected area, patients may present using a new assistive device for ambulation. For example, patients walking independently may present with a cane or walker, and patients initially using a walker may present in a wheelchair due to the significant pain with axial load from standing.

Patients may experience tenderness to palpation of the spinous process of the affected vertebral body, usually in the midthoracic region. Some patients will note an exacerbation of symptoms with leaning forward and improvement in symptoms with back extension. For the majority of patients, the motor and sensory neurologic examination is normal and limited only by pain rather than neurologic dysfunction.

STUDIES (LABS, X-RAYS)

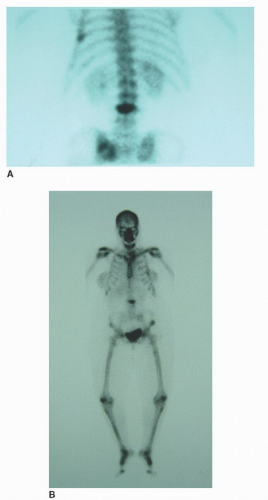

The plain radiograph is the primary imaging modality for the evaluation of VCFs. Loss of anterior vertebral body height relative to the posterior height on lateral x-rays (wedgeshaped vertebral body) is typically indicative of a compression fracture. Generally, fractures are described by the overall percentage of height loss, although there is no evidence to suggest that greater loss of height correlates with more pain. The posterior border of the vertebral body should be examined for any significant retropulsion of bone into the spinal canal. A bone scan (Fig. 5-1) can identify abnormalities in other areas of the body than just the particular area of the spine being investigated.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree