7 Validation of clinical practice by research

Responsibility for the scientific credence that can be afforded osteopathic medicine rests largely within its own discipline. The osteopathic profession is obligated to question the value of teaching unsubstantiated doctrines, except within their historical perspective. Students and the profession should be encouraged to engage in active research. Research is needed both to establish the clinical efficacy of osteopathic therapeutic intervention and to elaborate the biological basis and physiological mechanisms that underlie the osteopathic principles of practice. Patient satisfaction is also an important measure of the quality of care.1 If there is to be a commitment to research, where should the osteopathic profession focus its research funds and activities?

Why Undertake Research?

Given the financial constraints placed upon health expenditure and the increasing pressure upon third-party payers to rationalize and limit costs, health professionals will be required to demonstrate efficacy of treatment. It will no longer be acceptable to claim that therapy is beneficial solely because individual patients report improvement after treatment. The challenge is to demonstrate that symptom improvement is a direct outcome of specific intervention rather than natural recovery and that this intervention is more effective and cost-effective than marketplace competitors. Bogduk2 argues that research is not an indulgence of academics, but constitutes the basis of best practice and quality assurance.

Various osteopathic authors have acknowledged the need for research and the importance of continuing to search for new knowledge.3–8 The need for research should be indisputable, but where should the osteopathic profession’s resources be concentrated? Bogduk and Mercer9 express a view that it is more valuable to demonstrate the efficacy of a therapy before one explores its mechanism. They suggest there may be limited value in utilizing scarce resources researching the underlying mechanisms of a therapy that may eventually be shown to be ineffective.

It would also be reasonable for a profession to hold the view that there is a place for both therapeutic trials and continuing research to explore the biological basis and physiological mechanisms that underpin osteopathic treatment. However, it should be recognized that, even if we had a clear understanding of the biological and physiological mechanisms underlying all osteopathic therapeutic interventions, this in itself would not prove that their use would produce a positive clinical outcome. Only properly conducted clinical trials can legitimize a therapy by demonstrating positive outcomes from therapeutic intervention. Many government bodies, professional associations and third-party payers promote evidence-based guidelines for the management of musculoskeletal pain.10–15 However, such guidelines are often promoted without evidence of their effectiveness.16 Willem et al17 noted that all national guidelines on the management of low back pain included the use of spinal manipulation. However, the data upon which national recommendations are based has been interpreted differently leading to conflicting guidelines between countries for the use of spinal manipulation in the management of both acute and chronic back pain.

Where Should Research Be Focused?

Research effort should be directed towards designing and implementing effective therapeutic trials that could demonstrate the efficacy or otherwise of therapeutic interventions.9 Validation of osteopathic practice by outcome studies is essential. Management of patients utilizing outcome measures has the benefit of establishing baselines, documenting progress and assisting in quality assurance.18

Osteopathic practice is diverse. Individual practitioners, depending upon their style of practice and interests, treat a wide variety of different complaints. Osteopaths see and treat a significant number of patients presenting with spinal pain.19,20 Outcome studies on patients presenting with spinal pain and disability are an obvious area for osteopathic research. Despite this fact, there is a paucity of osteopathic outcome studies. The studies that have been published included small patient numbers, variability in methodology and outcomes.20

Various authors4,8,21–23 highlight the point that there are significant difficulties associated with clinical research in the osteopathic area. Stoddard21 emphasizes that clinical research in osteopathy is hampered by the complexity and diversity of the presenting problems and the difficulties associated with patient allocation to syndrome groups that vary constantly over time. Although there has been a focus upon quantitative research it is increasingly recognized that qualitative research has a distinct and important contribution to make to healthcare research.24 Qualitative research has not often been used as an evidence resource for systematic reviews. As individualized patient treatment is complex, research should utilize and value both qualitative and quantitative research methods.25 However, similar problems associated with clinical research exist for other disciplines practising manual therapies. Despite the difficulties, other disciplines are participating in an increasing number of research projects.

Patient Classification

A possible spectrum of research designs would include conventional and unconventional group designs, ethnomethodological designs and single case studies.26 Each research method has advantages and limitations, with varying applicability, differing ranges of validity and ethical constraints and will generate differing sets of data. Which approach would be most useful for outcome studies in osteopathic medicine? The nature of the research question should guide the selection of research design.

Palpatory findings are integral to the establishment of an osteopathic diagnosis. For palpatory diagnosis to be useful for classification purposes, good reliability needs to be demonstrated. Many studies and systematic reviews indicate that inter- and intra-examiner reliability for palpatory motion testing without pain provocation is poor.27–38 For these reasons, current osteopathic diagnostic labels cannot be used effectively in clinical trials of spinal pain and disability and an alternative means of classification needs to be identified.

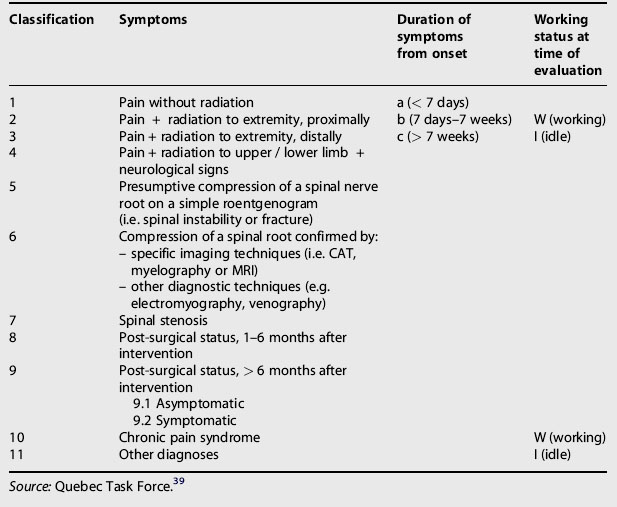

The Quebec Task Force39 recognized the lack of uniformity in diagnostic terminology used for spinal disorders and proposed a classification that did not depend upon pathological entities, but reflected the clinical presentations encountered in practice. A modified form of this classification has been utilized for conducting research. This classification system had the merit of enabling clinicians, regardless of discipline, to categorize patients with spinal pain in the clinical setting and it links patient symptomatology with duration of symptoms and working status (Table 7.1). The Quebec Task Force classification consisted of 11 categories with classification based upon historical markers and clinical and paraclinical examinations. Some categories were further subdivided by stage (i.e. acute, subacute and chronic) and whether the patient is able to work.

Some authors suggested different methods of patient classification.40,41 DeRosa and Porterfield41 modified the Quebec Task Force classification for spinal pain, making it more appropriate for physical therapy diagnosis (Table 7.2).

Table 7.2 Modified physical therapy diagnosis classification

| Category | Definition |

|---|---|

| 1 | Back pain without radiation |

| 2 | Back pain with referral to extremity, proximally |

| 3 | Back pain with referral to extremity, distally |

| 4 | Extremity pain greater than back pain |

| 5 | Back pain with radiation and neurological signs |

| 6 | Post-surgical status (< 6 months or > 6 months) |

| 7 | Chronic pain syndrome |

Source: DeRosa and Porterfield.41

Categorizing patients using the Quebec Task Force or a similar system of classification enabled outcome studies to be performed on groups of patients with spinal pain without the need for a specific osteopathic or mechanical diagnosis. This did not obviate the need for the practitioner to undertake a full and thorough assessment of each patient, but allowed classification of patients into groups for the purpose of research. This form of classification removed some of the obstacles to research associated with a lack of standardization and validation of diagnostic terminology in spinal disorders.

The Quebec Task Force42 published a similar classification for whiplash-associated disorders. This classification was said to ‘provide, categories that are jointly exhaustive and mutually exclusive, clinically meaningful, stand the test of common sense and are “user friendly” to investigators, clinicians, and patients’. This classification system allowed outcome studies on ‘whiplash’ patients to be undertaken.

These classification systems enabled patients to be placed into discrete sub-groups. A study by Brennan et al reported that practitioners demonstrated an ability, using signs and symptoms, to identify sub-groups of patients with low back pain and then match them to specific treatment approaches. Those patients matched by the practitioner to specific interventions showed statistically significant improvement when compared with non-matched controls.43 This indicates that within any population of spinal pain patients there are sub-groups of patients who are likely to respond better to one intervention than another and that practitioners have an ability to identify likely positive responders. Several classification systems for spinal and pelvic girdle pain have now been developed in an attempt to identify sub-groups of patients who are likely to respond positively to specific interventions.44–51

Are there historical and clinical features that would identify positive responders from non-responders to high-velocity low-amplitude (HVLA) thrust techniques? Research into the predictive value of specific clinical findings to identify patients with spinal pain who are likely to benefit from spinal manipulation has led to the development of clinical prediction rules. Clinical prediction rules consist of combinations of variables obtained from self-report measures, patient history and examination that assist in identifying those patients with spinal pain most likely to respond to spinal manipulation.52–55

Measuring Outcomes

1. The researcher must identify what he or she wishes to measure, e.g. spinal pain and disability.

2. What is to be measured must be defined in quantifiable terms, e.g. the intensity of pain suffered by the patient, the impact the pain and disability have upon the patient’s activities of daily living and work, etc.

3. Selection of appropriate data collection and recording instruments that will give reliable and valid results.

Broadly speaking, outcome measures attempt to quantify pain, physical impairment, limitation of activity, impact upon work and leisure and psychosocial factors. It is recommended that a full evaluation of spinal disorders should include a disability measure, a general health measure, a pain scale, a measure of employment and a measure of patient satisfaction (Table 7.3).56 Although patient records are easily accessible to the practitioner, there are problems associated with this form of data collection for the purpose of outcomes assessment. Recording in patient records lacks standardization and is often incomplete and what is recorded may not reflect what has actually occurred. Practitioners also record physical examination findings, but the large variability in normal values and poor inter-examiner agreement limit the use of such tests in research.

Table 7.3 A proposed set of patient-based outcome measures for use in spinal disorders

| Domain | Instrument |

|---|---|

| Back specific function | Roland–Morris or Oswestry |

| Generic health status | SF-36 version 2.0 |

| Pain | Bodily pain scale of SF-36 |

| (optional) Chronic Pain Grade | |

| Work disability | Work status |

| Satisfaction: back specific | Days off work and days of cut down work |

| Time to return to work | |

| Satisfaction with care: Patient Satisfaction Scale | |

| Satisfaction with treatment outcome: Global question |

Source: Adapted from Bombardier.56

A variety of easily used tools has been developed that allow practitioners to assess specific outcomes resulting from therapeutic interventions. Liebenson and Yeomans18 identified eight categories of available outcome approaches (Table 7.4). Additional validated measurement instruments have been developed over time.

| Category based on assessment goals | Outcomes assessment instrument |

|---|---|

| 1. Pain level | Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|