Urinary Tract Infection

Edmond T. Gonzales

David R. Roth

EPIDEMIOLOGY

During childhood, the urinary tract is second only to the upper respiratory tract as a source of morbidity from bacterial infection. Urinary tract infection (UTI) is predominantly a problem in girls. However, for the first few months after birth, the incidence of urinary infection in the male exceeds that of girls. An uncircumcised boy has approximately a 1% chance of developing an infection during childhood, mostly in the neonatal period. In male neonates, the incidence of asymptomatic bacilluria is 1.5%, but it decreases to 0.2% by the time boys are of school age. In circumcised boys, the incidence of urinary infection is about one-tenth that of the uncircumcised. This observation, though, is not considered to be an indication for routine circumcision in the newborn because complications from circumcision potentially negate the benefit of reducing the incidence of urinary infections. At this time, no data exist to suggest that remaining uncircumcised increases the risk of UTI developing in older boys. A girl’s chance of developing an infection during childhood is close to 3%. Random screening of preschool and school-age girls has shown an incidence of asymptomatic bacilluria of 1%. The incidence peaks in children between age 3 and 5 years, the age that coincides with toilet training, and then returns to a baseline value of between 1% and 2%.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS AND COMPLICATIONS

The signs and symptoms of UTI in an older child are those seen in the adult population, namely frequency, dysuria, hematuria, incontinence, suprapubic or flank tenderness, lethargy, and fever. In the young infant, though, symptoms are more subtle. Weight loss is a prominent symptom, followed by irritability, fever, lethargy, and cyanosis. Thus, nonspecific complaints or problems should raise the suspicion of a UTI in a newborn, although fewer than 20% of infants with nonspecific complaints and only 18% of children with specific voiding complaints will actually have a UTI.

Documentation of urinary infection requires that a specimen be properly obtained. Of the several ways to collect an aliquot of urine from a child, the easiest, once a child has been toilet trained, is the midstream clean-catch specimen. Before toilet training is complete, three methods remain, each with its advantages and disadvantages. The simplest, but least reliable, is the U-bag. A negative culture from a U-bag is meaningful, but if the culture is positive, it is possible that the bacterium is a contaminant from the rectum, skin, or prepuce. Therefore, whenever this method produces a positive specimen, the culture should be repeated, utilizing a more accurate method. Two other procedures are available; both are somewhat more involved, but each should provide an uncontaminated aliquot of bladder urine. The first is a percutaneous bladder tap. In the neonate and infant, the bladder occupies an intraabdominal position, rendering suprapubic needle access easier than in older persons. However, if the bladder is not full, it can be difficult to locate. Occasionally, hematuria can result after a bladder tap. The second method is urethral catheterization. In the small girl, visualization of the urethra may be difficult, but with practice the procedure can be mastered easily. A small feeding tube (5 French or 8 French) is most appropriate for catheterization. Little risk of urethral trauma or introduction of bacteria into the bladder exists if standard care and antisepsis are used. Although routine urinalysis can suggest strongly that urinary infection is present, any treatment program should be based on an accurate culture and sensitivity. Consequently, obtaining the culture before antibiotics are started is imperative because a single dose of medication can give a false-negative result.

UTIs often are described based on the presumed location of the infection. Cystitis is a UTI that is confined to the bladder, whereas pyelonephritis involves the kidney. An accurate delineation between the two conditions is difficult to establish; however, clinical signs and symptoms do offer meaningful clues. High fever, nausea, vomiting, flank pain, and lethargy usually are associated with acute pyelonephritis, whereas dysuria, frequency, urgency, enuresis, suprapubic pain, and a low-grade fever are more common with cystitis. However, a crossover of symptoms does occur. Studies in adult patients with acute urinary infection, in which urine from the kidneys (obtained by ureteral catheterization after acquiring a bladder specimen) was negative, demonstrate that fever can be associated with cystitis. In fact, determining whether a patient with a positive culture from bladder urine also has bacteria in the renal pelvis or parenchyma is difficult. The traditional method used to obtain separate bladder and renal cultures involves ureteral catheterization, which requires anesthesia and is impractical in children. Currently, radionuclide renal imaging using dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA) is the most accurate and practical study available to demonstrate acute pyelonephritis. Decreased

parenchymal uptake of the isotope has been shown in animals to correlate clearly with areas of experimental infection. In the clinical situation, however, focal decreased uptake of the isotope noted during a febrile urinary infection also could represent an old parenchymal scar and not necessarily a new lesion. Therefore, the routine use of DMSA scanning is not practical during the acute episode because the findings on DMSA scanning do not change initial therapy for the acute infection. Nonetheless, DMSA renal scanning remains the most sensitive and least invasive technique available to distinguish cystitis from apparent pyelonephritis. No recognized relationship exists between the location of the infection and the organism responsible for the infection.

parenchymal uptake of the isotope has been shown in animals to correlate clearly with areas of experimental infection. In the clinical situation, however, focal decreased uptake of the isotope noted during a febrile urinary infection also could represent an old parenchymal scar and not necessarily a new lesion. Therefore, the routine use of DMSA scanning is not practical during the acute episode because the findings on DMSA scanning do not change initial therapy for the acute infection. Nonetheless, DMSA renal scanning remains the most sensitive and least invasive technique available to distinguish cystitis from apparent pyelonephritis. No recognized relationship exists between the location of the infection and the organism responsible for the infection.

THERAPY

Most UTIs can be treated adequately, on an outpatient basis, with a 7- to 10-day course of antibiotics. When shorter courses are used, the recurrence rate is higher. Initial treatment should begin after a urine specimen for culture and sensitivity has been obtained. A broad-spectrum agent such as amoxicillin (20 to 30 mg/kg/day, in three divided doses) or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (dosing is based on the trimethoprim content, at 6 to 12 mg trimethoprim/kg/day, divided every 12 hours) then is begun empirically, with therapy being adjusted, if necessary, after the culture and sensitivity results are available. A repeat culture, to confirm eradication of the infection, should be obtained approximately 1 week after the completion of treatment. A child with severe symptoms accompanying pyelonephritis often requires hospitalization for parenteral antibiotics and control of nausea and vomiting. For the child with frequently recurring infections (at least four a year), a long-term, low-dose daily prophylactic antibiotic (usually nitrofurantoin or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole at one-fourth to one-half of the therapeutic dose) is appropriate. Usually, the medications are given for 6 to 12 months. Subsequent follow-up should include regular urinalyses and cultures when indicated.

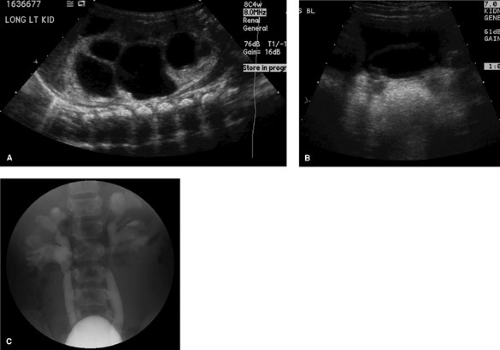

All children with a documented UTI should undergo adequate studies to evaluate the anatomy of the urinary tract. Generally, studies to evaluate both the lower tract (the urethra and bladder) and upper tract are suggested. This recommendation is based on the clinical observation that the children most likely to sustain renal parenchymal damage from infection are those who have an anatomic defect of the urinary tract (Fig. 321.1). The positive yield from these evaluations is age and sex-dependent and ranges up to 50% in young girls with pyelonephritis (primarily from discovery of vesicoureteral reflux). For the older girl with symptoms of only cystitis, one can argue that initially obtaining only an upper-tract study is sufficient because it will reveal any significant pathology. Any anatomic anomaly discovered might, of course, require additional work-up and individual treatment.

Imaging of the upper tracts nearly always is begun with the renal ultrasound. This study provides excellent anatomic detail, is independent of renal function, has no known untoward biologic effects, and is painless. Radionuclide renal scanning using DMSA is more sensitive at identifying focal scarring (Fig. 321.2), but seldom is used in the initial evaluation of a UTI. The intravenous urogram rarely is used today in the pediatric population. The diagnostic studies available to evaluate the lower

tract include either a voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG) or a nuclear cystogram. The VCUG provides optimal anatomic detail, allows for grading of reflux that may be present, and is the only study that delineates the male urethra. The nuclear cystogram is a sensitive test to identify the presence of reflux and results in somewhat less radiation exposure than the VCUG but offers poor anatomic detail. A nuclear cystogram is a better test to follow reflux over the long term. Cystoscopy and retrograde pyelography rarely are indicated in the work-up of a pediatric UTI.

tract include either a voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG) or a nuclear cystogram. The VCUG provides optimal anatomic detail, allows for grading of reflux that may be present, and is the only study that delineates the male urethra. The nuclear cystogram is a sensitive test to identify the presence of reflux and results in somewhat less radiation exposure than the VCUG but offers poor anatomic detail. A nuclear cystogram is a better test to follow reflux over the long term. Cystoscopy and retrograde pyelography rarely are indicated in the work-up of a pediatric UTI.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree