Upper Tibial Osteotomy (High Tibial Osteotomy)

Tomoyuki Saito

Yasushi Akamatsu

Ken Kumagai

DEFINITION

High tibial osteotomy (HTO) is realignment surgery, which has developed for treating medial compartment osteoarthritis (OA) of the knee.7

One of the main etiologic factors of knee OA is excessive biomechanical stress loaded on a focal area due to varus deformity of the lower limb alignment.

Excessive biomechanical stress is loaded onto either compartment of the knee joint; consequently, such overload is more likely to give rise to degeneration of articular cartilage with aging.

The aim of HTO is to correct malalignment of the limb, resulting in a transfer of weight bearing from the degenerated medial compartment to the relatively healthy lateral compartment.

Correction to appropriate knee alignment provides stability of the affected knee, subsidence of synovitis, and cease of cartilage degeneration.

The indications for HTO include medial compartmental knee OA with or without instability and osteonecrosis of the knee.

ANATOMY

The proximal tibial portion for osteotomy has several important anatomic landmarks to obtain successful results and avoid complications.

On the anterior aspect of the proximal tibia, the tibial tuberosity is the most prominent feature. The osteotomy should be carried out at the proximal level of the tuberosity.

Gerdy tubercle is located at 2 to 3 cm lateral to the tibial tubercle, which is the insertion of the iliotibial tract. Gerdy tubercle is the most suitable place to place fixative devices because of the thick cortical bone.

On the medial aspect of the proximal tibia, there are insertions of the pes anserinus, the gracilis, and semitendinosus covered with the fascia, and on the posteromedial portion, the superficial layer of the medial collateral ligament is attached. In cases of medial soft tissue tightness, these sometimes need to be elevated subperiosteally.

The anterior aspect of the proximal tibia and the fibula is the origin of the tibialis anterior, extensor digitorum longus, and peroneus longus muscles.

On the lateral side, the common peroneal nerve runs on the lateral side of the neck of the fibula. On excision of the fibular head or division of the proximal tibiofibular ligament in closing wedge osteotomies, much attention should be paid to avoid nerve injury.

The posterior neurovascular structure, including the popliteal artery and vein and tibial nerve, should be protected while the posterior portion of the tibia is osteotomized.

The cross-section of the proximal tibia has a triangular shape. In opening wedge high tibial osteotomies (OW-HTO), the posterior portion of the osteotomized site should be opened more than the anterior portion to avoid an expected increase of the tibial slope.

When performing fibular osteotomy in closing wedge high tibial osteotomies (CW-HTO), the fibular shaft can be resected safely at the level of about 16 cm distal to the fibular head.

PATHOGENESIS

Knee OA is a common joint disorder in elderly people that leads to progressive dysfunction of a knee joint.

Knee OA develops and progresses due to risk factors including heredity, weight, age, gender, repetitive stress injury, and high-impact sports.

Although the etiology of knee OA is multifactorial, medial compartmental knee OA reveals varus deformity, the mechanical axis passes through far medial side from a knee joint, and excessive mechanical stress loaded on the medial cartilage are considered to be main causative factors.

Excessive overload is more likely to give rise to degeneration of articular cartilage, and cartilage fragments entrapped by synovium induce synovial inflammation, resulting in further degeneration of articular cartilage.

Synovial inflammation is marked around the degenerated articular cartilage and related to joint swelling and provocation of pain.

NATURAL HISTORY

Once a knee joint is affected by OA, the disease advances with time, and osteoblastic changes, including subchondral bone sclerosis and osteophyte formation, are clearly visible. Further cartilage degeneration occurs, resulting in joint space narrowing or obliteration.

Range of motion (ROM) is gradually limited. Flexion contracture or restriction of the knee appears.

However, quadriceps strengthening exercise or reducing body weight can modify the clinical course of the disease. These measures may stabilize a knee joint and reduce overload applied on the cartilage-degenerative portion, providing good relief of pain.

As the disease progresses, loss of articular cartilage brings about varus-valgus instability, so-called “lateral thrust.” This instability promotes further cartilage degeneration, producing bony wear at the medial femorotibial articulation, and varus deformity increases.

Osteophytes formed around intercondylar notch and may cause anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) deficiency, and the disease expands to the lateral and the patellofemoral compartment.

A knee joint is destructed and knee function is markedly disabled due to severe pain and limited ROM.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Diagnosis of knee OA can be made based on patient-reported symptoms and physical and radiologic examination.

Clinical examination of the knee should start with complete history of the symptoms; past history, including previous trauma such as fracture or meniscus tear; medical diseases, including diabetes mellitus or hypertension; and occupational history.

Knee pain is a crucial clinical sign of knee OA. Patients experience pain around a knee joint when standing up from a chair and starting to walk. This pain modality, called starting pain, is very specific for knee OA. Pain is also aggravated by physical activities such as descending or ascending stairs.

Some patients complain of pain at night and morning stiffness.

Asking patients about the onset of pain, the duration and frequency, and physical activities that aggravate pain is essential to help make differential diagnosis.

The physical examination should cover posture, gait pattern, the involved limb, the joints on either side of the knee, the spine, and, particularly, the hip joint, which can also cause knee pain.

Observation shows that a significant varus deformity at the knee, antalgic gait, and lateral thrust in early stance phase of gait visualized joint effusion and quadriceps muscle atrophy.

Palpitation indicates the exact location of pain around the tibiofemoral and patellofemoral joints. Tender zones are easily determined by asking patients to point to painful sites with one finger. When joint effusion exists, a ballotable patella is noticed. Crepitation, defined as a cracking or grinding sound, is identified when the patient with knee OA experiences a sensation in the joint during physical examination.

Pain is often provoked at the medial joint space by valgusstressed maneuvers because more marked synovitis and osteophyte formation are present in medial compartmental knee OA.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Routine radiographic examination of knee OA consists of standing (weight bearing) anteroposterior (AP) and lateral views and tangential axial views. Other views include the tunnel view, 45-degree flexed weight-bearing posteroanterior (PA) view, varus or valgus stress views, and a full-length standing radiograph (a mechanical axis view).

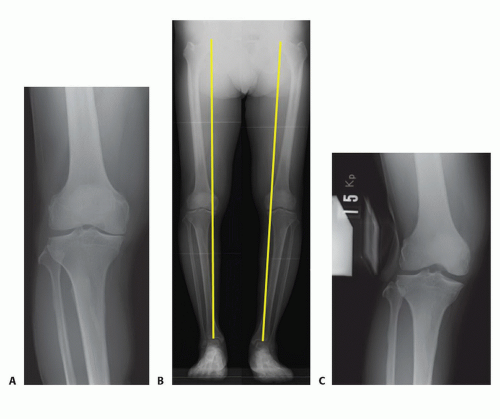

A standing AP view provides more accurate assessment of knee alignment and joint space width than one taken in the supine position (FIG 1A).

A lateral view depicts the status of the extensor mechanism, including the patella height (patella alta or baja), the quadriceps and patellar tendon, the tibial posterior slope, the distal end of the femur, and the proximal end of the tibia.

Morphologic changes of the patellofemoral joint can be assessed using a tangential axial view (the Merchant view).

The tunnel view demonstrates osteophytes formed on the posterior aspect of the intercondylar notch.

The flexed, weight-bearing PA view of the knee reveals the joint space width of the more posterior aspect of the femorotibial joint. Early degenerative changes of the articular cartilage can be detected with this view.

A mechanical axis view provides exact alignment of the whole lower extremity. This view is commonly used in preoperative planning of HTO (FIG 1B).

The varus and valgus stress views are helpful to visualize the stability of medial and lateral laxity in medial knee OA and to confirm that the lateral compartment is almost intact (FIG 1C).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provides multiplanar assessment of the pathology of the whole structure of a knee joint, including cartilage, synovium, ligaments, menisci, and bone marrow.

In medial compartmental knee OA, MRIs can satisfactorily depict the morphologic changes of articular cartilage from an irregular surface as the disease progresses, synovial hyperplasia, thick subchondral bone, the degenerative process of the medial meniscus, the condition of the ACL and medial collateral ligament, and bone marrow edema indicating overload applied to the articular surface.

Other diagnostic imaging tools include bone scintigraphy and positron emission tomography scan using fluorodeoxyglucose or 18F-sodium fluoride (18F-NaF).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Osteonecrosis of the femoral condyle

Osteonecrosis of the tibial plateau

Charcot joint

Idiopathic joint apoplexy

Elderly onset rheumatoid arthritis

Crystal-induced arthritis

Pyogenic arthritis

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Employment of a combination of pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatment is recommended for clinical practice (Osteoarthritis Research Society International recommendations for the management of hip and knee OA).25

Patients should be instructed about the purpose of treatment and the importance of changes in lifestyle, pacing of activities, weight reduction, and the need for walking aids to reduce overload to the joint.

A knee brace can reduce pain in knee OA with mild or moderate instability. Lateral-wedged insoles provide symptomatic relief for some patients with medial compartmental knee OA.

As pharmacologic treatments, acetaminophen is commonly used as an analgesic. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are recommended to be used at the lowest effective dose to prevent the increase of gastrointestinal risks. COX-2 selective agents should be used with caution in patients with cardiovascular risk factors. Glucosamine or chondroitin and weak opioids and narcotic analgesics may provide symptomatic benefits for patients with knee OA.

Intra-articular injections with corticosteroids or hyaluronate can be used in the treatment of knee OA.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Indications

The main indication for HTO is medial compartment knee OA, which does not provide adequate pain relief and functional improvement from a combination of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic treatment.17,18

Patients with knee OA with lateral thrust are likely candidates for HTO.

Patients with osteonecrosis of the knee are also good candidates for HTO.

The ideal patients are physiologically young (younger than 55 years). However, a higher failure rate in obese or elderly patients of older than 65 years is not always identified. Old age and overweight patients are not contraindications for HTO.

Medial compartmental knee OA with less than 15 degrees of anatomic varus angulation and fixed flexion deformity of less than 15 degrees is indicated for OW-HTO. For other cases, CW-HTO should be considered as a surgical option.

To perform HTO, the ACL must be functionally intact rather than insufficient. CW-HTO can decrease the tibial posterior slope and should be selected for ACL-deficient knee OA.

Inflammatory knee arthritis or knee OA with involvement of both the medial and lateral compartment is not indicated for HTO.

Preoperative Planning

At the beginning of preoperative planning, it is extremely important to check that the lateral joint space width is maintained in valgus-stressed AP knee radiographs because the postoperative main weight-bearing portion becomes the lateral compartment.

In planning for osteotomy, it is a basic principle to determine the location and direction of the osteotomy line and the desired angle of correction.

Using a standing AP knee radiograph, a single osteotomy line is drawn from 35 mm of the point of the medial tibial cortex distal to the medial joint line to the proximal tibiofibular joint.

The desired postoperative knee alignment is 170 degrees of standing femorotibial angle (SFTA), which was proposed by Bauer and associates4 (10 degrees of anatomic valgus angulation). The desired angle of correction (θ°) is the angle calculated by subtraction of 170 degrees from the SFTA of the affected knee.

From a point of intersection of the osteotomy line to the lateral tibial cortex, the base of a triangle (θ) is drawn, and the distance from the initial point of the osteotomy line to the point of intersection to the medial cortex is measured, which indicates the tibial width for opening the gap during operation.

Positioning

The patient is positioned supine on the operating table with a sandbag inserted into the ipsilateral buttock region to place the lower extremity in neutral position (FIG 2).

FIG 2 • Positioning. Patient is in the supine position. A tourniquet is placed at the upper thigh area.

A pneumo-tourniquet is applied to the upper thigh area.

Under preoperative fluoroscopy, it is necessary to check that the center of the femoral head, the ankle, and the position of the knee joint can be visualized.

Approach

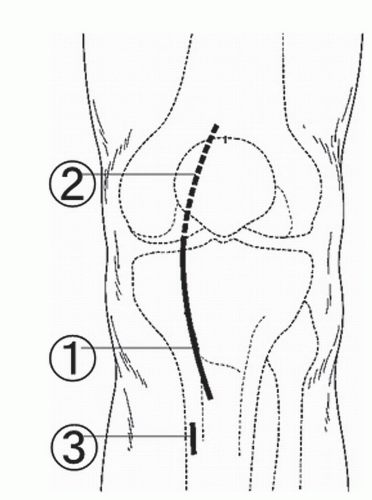

The approach for OW-HTO is a medial parapatellar incision from the lower part of the patella to 3 cm distal to the tibial tuberosity (FIG 3).

When arthrotomy is needed for intra-articular procedures, including resection of osteophytes and resourcing articular cartilage, a longer skin incision is made from the upper part of the patella to distal to the tibial tuberosity, and the subvastus approach is commonly used.

TECHNIQUES

▪ Arthroscopy

A routine arthroscopic examination is performed through the anteromedial or anterolateral portal to determine the intra-articular pathology.

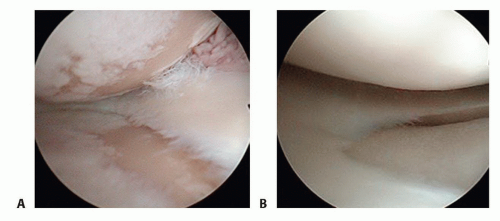

It is important to check the status of the articular surface of the lateral compartment because derangement of the articular cartilage influences the long-term clinical outcomes of HTO (TECH FIG 1A,B).

The condition of the ACL and the patellofemoral compartment are also investigated because OW-HTO is feasible to exacerbate the patellofemoral arthritis.

During arthroscopy, free body can be removed and meniscus tears are débrided if necessary. Bone marrow stimulation can be performed using a Kirschner wire or an ice pick.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree