Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty

In theory, unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) is an attractive alternative to osteotomy and total knee arthroplasty (TKA) in selected osteoarthritic patients. Advantages of UKA over osteotomy include higher initial success, fewer early complications, greater longevity, better cosmetic limb alignment, easier conversion to TKA, and the potential to perform bilateral procedures on the same day. Later conversion of osteotomy to TKA is potentially complicated by many factors (see Chapter 9).

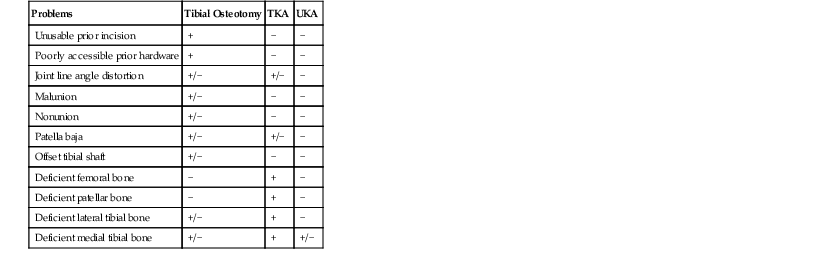

Advantages of UKA over TKA include the preservation of both cruciate ligaments, resulting in more normal knee kinematics and potential for a higher level of performance. Bone stock is preserved in the opposite and patellofemoral compartments, allowing easier conversion to TKA should this be necessary. Initial reports from my institution did not confirm that UKA conversion was necessarily an easy procedure.1 A later report, however, showed that if the UKA was done in a conservative fashion, conversion was easy and results were the same as those for primary TKA.2 Potential revision problems involved in osteotomy, TKA, and UKA conversion are listed in Table 16-1. In UKA, the only potential revision problem should be medial tibial plateau deficiency treated with bone graft or metal wedge augmentation (see Chapter 11).

Despite these arguments, UKA has been a controversial procedure since its introduction in the early 1970s. Initial reports were discouraging regarding UKA in medial compartment osteoarthritis.3,4 A few years later, R. Santore and I published more favorable results using the unicondylar prosthesis.5 We studied 100 knees with 2- to 6-year follow-up. Three repeat operations had been performed, for an incidence of revision of roughly 1% per year at this short follow-up. The average flexion was 114 degrees, significantly better than in any contemporary reports using bicompartmental arthroplasty. When the same series was followed at 5 to 9 years (mean 7 years), seven revisions had been performed for a revision rate continuing at 1% per year.6 The total condylar experience at that time for the same follow-up also showed a revision rate of 1% per year.7 Armed with this information, our enthusiasm for unicompartmental arthroplasty began to grow. We felt that when the knee was exposed for arthroplasty and the patient fulfilled the criteria for unicompartmental replacement, it was reasonable to perform this procedure on these patients. By the early 1980s, approximately 10% of my patients with osteoarthritis underwent unicompartmental replacement.

Reasons for failure of UKA included patient selection, prosthetic design, and surgical technique. We learned the lesson that patients with lateral compartment arthritis and a lax medial collateral ligament (MCL) could not be stabilized by a unicompartmental procedure (Figure 16-1). We also began to see failures in obese patients. These were due to either tibial or femoral loosening. We saw some femoral component loosening by subsidence into the subchondral bone (Figure 16-2). The force across the knee in level gait is approximately three times body weight. This force is ideally distributed evenly to the medial and lateral compartment over the surface area provided by each compartment. The pounds per square inch increase if more pounds and fewer square inches are covered by the prosthetic components. The relatively small size of early UKA components therefore made them vulnerable to loosening in heavy patients.

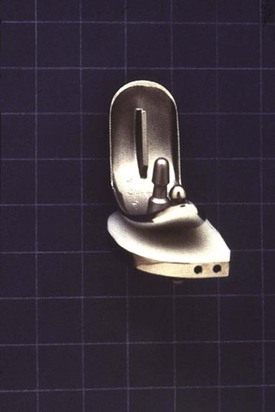

To address this issue, P. Walker and I redesigned the unicondylar prosthesis to the Brigham unicompartmental knee in 1981 (Figure 16-3). The femoral component was made 5 mm wider to better cap the subchondral bone and resist subsidence. The tibial component was a nonmodular, metal-backed component with a composite thickness starting at 6 mm (Figure 16-4). The articulation was flat-on-flat to diminish stress on the polyethylene and increase surface contact. We used this prosthesis exclusively for the next 8 or 9 years. The specifics of its design and surgical technique taught us more important lessons about unicompartmental arthroplasty.8

Because the articulation was flat-on-flat, it became apparent that imprecise surgical technique was unforgiving. If the component articulating surfaces were not parallel during weight-bearing, edge-loading would occur, leading to accelerated wear of the polyethylene (Figure 16-5). We also learned that mediolateral and rotational congruity between the components must be assessed in extension rather than flexion. Through the classic median parapatellar approach with patellar eversion, the tibia is artificially externally rotated in flexion owing to the force of the everted quadriceps. Normally, of course, the tibia tends to internally rotate in flexion. If component congruency is assessed in flexion, it will give an inaccurate view of component congruency when the quadriceps is relocated and the patient bears weight in extension.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree