Chapter 1. Understanding dementia

CHAPTER CONTENTS

Introduction1

What is dementia?2

Living with primary dementia6

The nature of the neurological impairment8

Memory19

Conclusion23

INTRODUCTION

▪ memory loss

▪ language difficulties

▪ difficulties with spatial awareness and skilled movement

▪ a loss of knowledge and understanding of the world

▪ problems with reasoning, planning and judgement

▪ changes in personality, behaviour and emotional control.

Even these sub-categories are quite broad and cover a lot of different specific problems and difficulties and there is considerable variation from one person to the next in the particular mix of symptoms they experience. The aim of this chapter is to explain what dementia is and what causes it. To work successfully with people with dementia it is important to have a sound understanding of the condition they are living with. As part of this explanation, the chapter will outline the basic organisation of the human brain and reveal the parts that are most vulnerable and least vulnerable to damage in dementia. This provides a basis not only for understanding why certain symptoms are common amongst people with dementia, but also for why we need to recognise the individuality of the person with dementia. It is important that we do not assume that the dementia is simply ‘global intellectual decline’ but undertake a careful assessments of both lost and preserved abilities in a person with dementia. The chapter will also explain why brain damage must be set in a wider context that covers the person’s past and present circumstances. The chapter will show how we can use knowledge about the brain, and in particular the organisation of memory functions, to move into the mind of the person with dementia and take on their perspective of the world. This perspective is central to understanding the needs and behaviour of a person with dementia and providing care that promotes their wellbeing.

WHAT IS DEMENTIA?

The current definition of dementia by the World Health Organization (1993), in the 10th edition of its International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10), is:

‘A syndrome due to disease of the brain, usually of a chronic or progressive nature, in which there is disturbance of multiple higher cortical functions, including memory, thinking, orientation, comprehension, calculation, learning capacity, language and judgement. Consciousness is not clouded. The impairments of cognitive function are commonly accompanied, and occasionally preceded, by deterioration in emotional control, social behaviour or motivation. This syndrome occurs in Alzheimer’s disease, in cerebrovascular disease, and in other conditions primarily or secondarily affecting the brain.’

This definition makes it clear that the core symptoms of dementia (that is, the problems with memory, the confusion, the difficulties with language and understanding, the changes in emotion and behaviour) are primarily due to damage to the brain. The above definition also makes clear that there are many different challenges to the brain that can cause the symptoms of dementia. Thus, the word ‘dementia’ does not refer to a specific disease, but rather is an umbrella term which covers many different forms of disease and damage to the brain that affect its ‘higher’ or ‘cognitive’ functions. The most common causes of dementia are summarised in Table 1.1.

| Common primary causes | Common secondary causes |

|---|---|

| Alzheimer’s disease | Vitamin B deficiency |

| Vascular dementia | Hypothyroidism |

| Lewy body dementia | Depression |

| Frontotemporal dementia |

Some of these causes affect the brain directly (primary causes) whilst others are indirect (secondary causes). Secondary causes cause some kind of disruption to normal processing within the brain but do not damage the structure of the brain. Because the structure of the brain has not been damaged these dementias can often be reversed through successful treatment of the underlying condition. Table 1.1 shows that the most common secondary causes are vitamin B deficiency, hypothyroidism and depression. For people with secondary dementia the prognosis is good and they do not face the long-term challenges associated with the primary dementias.

The focus of this book is to improve the prospects for quality of life and wellbeing for those with primary dementia, for whom the prognosis is more challenging. These are the dementias that directly damage the brain and are irreversible and usually progressive. The most common form of primary dementia is Alzheimer’s disease (accounting for 50–60% of all dementias). Alzheimer’s disease is a neurodegenerative disease that slowly strips cells out of the most developed parts of the brain. The usual duration of the disease is 4–6 years, although there is huge variation, with some people dying within a year or two and others experiencing a gentler trajectory of decline that can span over two decades (Corey-Bloom & Fleisher 2005). The disease is recognised at post-mortem by its hallmarks, senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, within the brain tissue. In recent years much has been learnt about this disease, but it is a complex process and debate continues about what causes it: whether the plaques and tangles cause cell death, or whether they are simply the only visible by-products of dysfunctional cellular processes that have yet to be revealed and understood (for a review see Whalley 2001).

Cerebrovascular damage (vascular dementia) is also a significant cause of dementia, accounting for about 20% of all dementias. The term vascular dementia covers all dementias which are primarily caused by a problem with the blood supply to the brain. The most common form is multi-infarct dementia, a condition in which the person develops a vulnerability to tiny strokes (sometimes called ‘mini strokes’ or ‘strokelets’). In the early stages the brain damage that results from these small strokes is too minimal to cause any noticeable change to the person’s skills and intellect, but as the damage accumulates the symptoms of dementia emerge and develop.

Other recently recognised significant causes of dementia are Lewy body dementia and frontotemporal dementia. Like Alzheimer’s disease, these are both neurodegenerative processes that progressively kill brain cells. The causes and mechanisms of these processes, like those of Alzheimer’s disease, remain only partially understood. The process underlying Lewy body dementia leaves a different pathological hallmark within affected nerve cells – the Lewy body, a small, spherical deposit of insoluble protein. Post-mortem studies have revealed that Lewy body disease and Alzheimer’s disease often exist together. Indeed, mixed causes of dementia, sometimes called ‘the mixed dementias’, are common (Esiri et al 2001). The processes underlying the frontotemporal dementias are recognised by the very severe atrophy, or thinning, of brain tissue in the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain (key areas of the brain which will be introduced and explained in the latter half of this chapter). Pick’s disease is a particular form of frontotemporal dementia, again recognised at post-mortem by a particular neuropathological hallmark within damaged cells called the Pick body.

If you wish to learn more about the nature of these diseases, the best place to start is the Alzheimer’s Society website which has an excellent factsheet about each one. Were you to delve into medical textbooks on the topic you would find that whilst these are the major causes of dementia there are numerous other rare causes of primary dementia, including Creutzfelt–Jakob disease. It is possible to generate lists of causes with over 50 entries but taken together the rare causes account for only 1–2% of all primary dementias.

It remains impossible to diagnose the underlying cause of a primary dementia with 100% accuracy. There are no clinical tests that can confirm that the pathology of Alzheimer’s disease, Lewy body disease or frontotemporal dementia is developing within a person’s brain. Vascular dementia is related to general indices of vascular health (e.g. diabetes, high cholesterol and high blood pressure) but these are remote indices and do not give a precise indication of the degree to which the brain may be affected by vascular damage. Each form of dementia has characteristics which help clinicians to make a diagnosis of cause (see Table 1.2 below), but there is much variation and overlap in how all these conditions manifest, meaning that in some cases it is impossible to be sure what is causing the dementia.

| Cause (Key Diagnostic Guideline) | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Alzheimer’s disease McKhann et al (1984) | Memory loss is first symptom and dominates symptom profile during early years |

| Loss of abilities is gradual but continual | |

| Vascular dementiaRoman et al., 1993 and Chui et al., 1992 | Memory loss is probable but does not dominate the symptom profile |

| Loss of abilities more ‘patchy’ depending upon where exactly mini-strokes occur | |

| May be early loss of more basic sensory and motor functions | |

| Exists alongside signs of poor vascular health (high blood pressure, high cholesterol etc.) | |

| Lewy body dementiaMcKeith et al (1996) | Fluctuating cognitive ability |

| Visual hallucinations | |

| Parkinsonian symptoms | |

| Frontotemporal dementiaThe Lund and Manchester Group (1994) | Changes in either |

| (a) personality, social and emotional control | |

| or | |

| (b) language are more dominant than, and precede, memory loss |

With the neurodegenerative conditions (Alzheimer’s disease, Lewy body disease and frontotemporal dementia) the progression of symptoms is usually continual, but Lewy body dementia and frontotemporal dementia tend to progress at a faster rate than Alzheimer’s disease. Lewy body disease is associated with more day to day fluctuations, more of a ‘good-day, bad-day’ pattern, than Alzheimer’s disease, whilst vascular dementia often has a ‘stop-start’ or ‘stepwise’ pattern to the progression, each step down representing the occurrence of a new ‘mini-stroke’. These characteristics have been incorporated into diagnostic guidelines which are recognised internationally (Table 1.2). Such developments represent significant progress from the days when a general diagnosis of dementia was considered sufficient and was often applied without diagnostic rigour to explain any situation in which an elderly person’s behaviour appeared to depart from the norm. Nonetheless, there is still much work to be done in finding the markers that will allow clinicians to make an early and accurate diagnosis of cause.

With respect to the specific symptoms of the different primary dementias, it is worth noting that the symptom profile for dementia as a general syndrome has been strongly influenced by the specific symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease. Because Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of dementia, the stereotype of dementia is driven by the characteristics of this particular disease. This has over-shadowed the fact that the less common causes have slightly different symptom profiles. Thus, whilst memory loss is a central feature of Alzheimer’s disease, because this particular disease process is focused in the parts of the brain essential for memory function, it is a less prominent feature of the other forms of dementia, where the damage may be focused in other areas of the brain. Vascular damage can strike anywhere within the brain, meaning that the pattern of symptoms that occurs in vascular dementia may be more random and include more basic problems with sensory and motor functions (e.g. visual field cuts, poor gait, muscle weakness, stuttering speech, general motor slowing/clumsiness, incontinence) even when the intellectual problems, which are the core of the dementia syndrome, remain relatively mild.

Frontotemporal dementia is focused (as its name suggests) in the frontal lobe and temporal lobe of the brain, regions that are essential for social and emotional control. Memory is usually retained in the early stages of this disorder, but there are drastic changes to personality and behaviour, with behaviour becoming impulsive, reckless and inconsiderate. Often this condition is confused with functional psychiatric conditions and is not recognised as being a form of organic brain disease. This creates particular difficulties for the person and their family because it is assumed that the change in personality and behaviour is a functional problem (that is, something wrong with the person’s mind or attitude) when in reality the cause is an aggressive form of brain damage that is quite beyond the person’s control.

Turning finally to Lewy body disease, there is some overlap between this condition and Parkinson’s disease. The symptom profile of Lewy body dementia often includes Parkinsonian features such as mask-like facial expressions, a shuffling gait or tremors. This form of dementia is also associated with visual hallucinations and greater instability of cognitive function, periods of lucidity alternating with periods of deep confusion, as referred to above.

A careful medical history of the nature and onset of the symptoms of a dementia, combined with other essential investigations, such as blood tests to check for secondary causes and brain scans to check for strokes or tumours, usually leads to a correct diagnosis of the underlying cause. Post-mortem studies show that careful application of the diagnostic guidelines referenced above leads to high, but not perfect, accuracy rates (for review see Ballard & Bannister 2005). There is debate about whether dementia should be diagnosed (Drickamer & Lachs 1992). GPs face real anxieties in relation to diagnosing dementia (Downs, 1996 and Downs et al., 2002) and many are reluctant to make a diagnosis, particularly directly to the person with dementia, on the grounds that a diagnosis is not helpful when there is so little that can be done to cure or treat the condition (Vassilas and Donaldson, 1998 and Renshaw et al., 2001). However, there is evidence to suggest that a thorough investigation and diagnosis is helpful to people with dementia and their families, and there is growing agreement that the decision as to whether or not the diagnosis is given should lie with the person with dementia rather than the clinician (Meyers 1997). Being told that you have an irreversible and progressive brain disease is always going to be bad news, but identification of the cause can reassure people that there is a reason for the change and reduces stress (Audit Commission 2002).

Recent guidelines highlight the importance of early and accurate diagnosis in enabling people with dementia and their families to adapt (Department of Health 2001, National Institute for Clinical Excellence 2006, National Audit Office 2007). Furthermore, in the long-term, the development of cures or effective pharmacological treatments depends critically upon understanding and addressing the specific causes of dementia, and so it is vital that research into how to understand and detect the different forms of dementia continues. However, sadly, it is likely that cures for any of the common forms of dementia remain a long way off. In the meantime, for the person with dementia and those who care for that person, understanding how to respond to changes in memory, cognition and behaviour is of more central concern than understanding what is causing those changes. Regardless of underlying cause, the symptoms of dementia are best regarded as cognitive disabilities, challenges that require adaptation and support, rather than signs of a terminal and irreversible disease about which nothing can be done. The importance of adopting a positive attitude towards people with dementia will be discussed in more detail in the next section.

LIVING WITH PRIMARY DEMENTIA

Living with a primary dementia is extremely challenging. Because there is direct damage to the structure of the brain in primary dementia, these forms of dementia cannot be reversed, and pharmacological treatments are limited to the anti-dementia drugs. These drugs do not repair the damage to the structure of the brain, but seek to help the brain cells that remain to communicate effectively with one another by boosting levels of a key neurotransmitter called acetylcholine. These drugs have been shown to delay cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease, but whilst the effect is reliable, the size of the effect is modest (Takeda et al 2006). The minimal size of the benefit has led to the recent decision of NICE to restrict prescription of these drugs on the NHS to those whose dementia is moderate (NICE, 2006). Those with mild dementia and severe dementia are not thought to benefit enough for the costs to be justified. The decision, however, is very controversial. Experts have questioned the clinical basis for the decision (it is very hard to give someone with mild Alzheimer’s disease a diagnosis but tell them they must wait until they deteriorate further before they can be treated) and also the suitability of the cost–benefit analysis undertaken by NICE (O’Brien 2006). NICE’s guidance has caused extreme anger amongst people with dementia and their families, and key charities, such as the Alzheimer’s Society, have organised campaigns to get the decision reversed. The drug companies that produce the drugs have also challenged the guidance, leading to the first ever Judicial Review of a NICE decision. The Judicial Review concluded in August 2007 with a decision that changes to the guidelines were required regarding the use of the MMSE score (Folstein et al 1975) to ensure that the disability and race discrimination law is not breached, but that in other respects the NICE guidance was to be upheld, meaning that people with mild Alzheimer’s disease will not have access to these drugs on the NHS. Neil Hunt, Chief Executive of the Alzheimer’s Society, said in a statement on 27 September 2007 that the Society would not appeal against the decision, but reiterated that the guidance made no sense from a clinical, monetary or moral perspective.

As noted earlier, the lack of effective biomedical treatments for the causes of dementia has led many doctors and other health professionals to take a negative and pessimistic view of the condition (Audit Commission 2002 and National Audit Office, 2007). The belief that nothing can be done to help people with dementia contributes to the poor level of provision of services to help people with dementia live with the disabilities their brain damage causes, so it is vital that this belief is challenged. Furthermore, because the symptoms of dementia are within the realm of the intellect it is easy to overlook the fact that there is a physical cause for the symptoms. Damage to the parts of the brain that support memory will cause memory loss as surely as damage to the spinal cord will cause paralysis. Dementia does not operate within a ‘mind realm’ which is quite independent of the body and therefore subject to the law of ‘mind over matter’ rather than ‘cause and effect’. Lecturing, disciplining, arguing with, pleading with, despairing of or drilling people with dementia with respect to forgotten facts and lost skills is not going to bring those skills back. But this is not cause for pessimism. There is a direct parallel with physical disabilities – the extent to which a person is disabled by intellectual or cognitive disabilities depends to a large extent upon the level and quality of support that is provided to help them live with those disabilities.

The answer to the negative view for the prospects for people with dementia is not to deny that they have a progressive and incurable condition, but rather to recognise that progressive and incurable is not synonymous with hopeless and pointless. It is possible to accept the reality of primary dementia and still be positive. Although it is not possible to cure dementia, it is possible to radically transform the nature of the care and support that is provided to those who are affected (Kitwood, 1997 and Brooker, 2007). The more people see that people with dementia, when given the correct support and care, can live rewarding and happy lives, the less cause there will be for fear of the condition.

The remainder of this chapter will explain the nature of the neurological impairments of dementia in more detail in order to demonstrate that personhood (Rogers, 1961 and Kitwood, 1997) that is, a person’s subjective experience of having a sense of being, agency and unity as a unique human being, persists even when abilities such as memory, knowledge and language are lost. Loss of these so-called ‘higher cognitive abilities’ raises serious challenges to life, in particular dependency, but these losses do not rob a person of subjective existence. Memory and cognition are very important to our sense of self, and our expression of self, but the brain supports many other functions beyond memory and cognition and we are more than memory and cognition. Occupation and activities tailored to the person’s remaining strengths are essential to a person’s sense of wellbeing. Correct assessment of a person’s abilities and disabilities requires both a general understanding of the organisation of functions within the brain, and an ability to apply that general knowledge to a particular individual through careful observation. This chapter will outline the general knowledge of the brain and its functions, which is required as an underpinning, whilst the remainder of the book will deal with the more complex task of assessing individuals and developing tailor-made strategies for individual people with dementia.

THE NATURE OF THE NEUROLOGICAL IMPAIRMENT

The vast majority of people you work with will have dementia because of underlying brain damage. This does not, however, mean that brain damage is the only thing influencing their experience and behaviour. A key purpose of this chapter is to explain how brain damage interacts with psychological factors (such as personality and life history) and social factors (attitudes to dementia, the behaviour of other people towards the person with dementia) in determining the expression of a person’s dementia and their lived experience of that dementia.

Kitwood, 1989 and Kitwood, 1997 recognised a complex interplay between brain states and psychological states and stressed the importance of seeing neurological impairment (i.e. brain damage) as just one component of dementia. His position is elegantly captured in his equation:

the PERSON with dementia

not

the person with DEMENTIA.

This raises some problems with explaining the nature of the neurological impairment that underpins dementia. With dementia being an umbrella concept having many possible underlying causes, it is impossible to be definitive about the nature of the neurological impairment. Each cause, as explained above, affects the brain differently. On top of that, each person with dementia is an individual and there will be differences even within a cause as to how that person’s brain has been affected and damaged. Psychosocial factors, such as personality and life-history, add further variability in terms of how neurological impairment expresses itself. Kitwood’s message that each person with dementia must be treated as an individual, and not as a generic instance of dementia, cannot be stressed strongly enough (Kitwood 1997). Nonetheless, there are broad principles that can be drawn out which are helpful for understanding the challenges people with dementia face as a consequence of their condition.

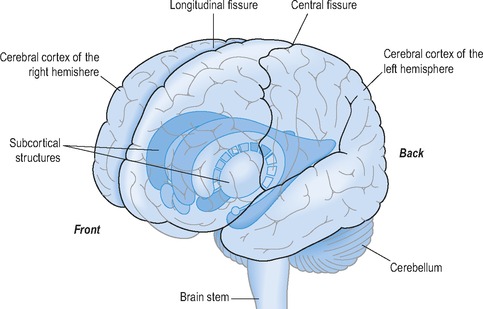

First, the core symptoms of dementia are associated with damage to a particular part of the brain called the cerebral cortex. The human brain is not a single structure but a whole nest of interacting structures. Different parts of the brain have evolved at different times and each structure has a specialised function within the brain’s overall goal of regulating the body and behaviour to meet the needs and desires of its owner. The brain is divided into three main sections (hindbrain, midbrain and forebrain) with each section containing a cluster of individual structures. The structures of the hindbrain are found in the brain stem (Fig 1.1) which is an extension of the spinal cord. Structures of the midbrain, and in particular the forebrain, have become greatly enlarged during human evolution. Figure 1.1 also shows the cerebellum (part of the midbrain), a largish structure that sits at the back of the brain underneath the two enormous cerebral hemispheres that form the forebrain, the two hemispheres being divided by a deep cleft in the brain called the longitudinal fissure (also shown in Fig 1.1). The forebrain contains a multitude of structures, and of these the cerebral cortex is the largest.

Figure 1.1 shows that the cerebral cortex is a sheet of nerve cells that covers the entire outer surface of the two cerebral hemispheres that comprise the forebrain. The cortex is thin, but in terms of surface area, it is vast. If it were pulled off the surface and laid flat it would measure nearly a metre square. Within the sheet are millions upon millions of nerve cells, capable of making trillions upon trillions of connections with one another. These connections support the most advanced aspects of human intelligence, such as conscious perception, knowledge, reasoning and decision-making. However, the cortex can only achieve these amazing functions by working with the whole hierarchy of structures underlying it, going right back down to the humble body. Without the body the cortex would not know anything or be able to do anything. Without ‘delegating’ the more mechanical or procedural aspects of control to other structures in the brain and spinal cord it would be overwhelmed.

Figure 1.1 also shows that there are many subcortical structures lying beneath the cortex (in fact those illustrated are only a small portion of all those structures). In isolation from the subcortical structures that lie beneath it, the cerebral cortex, despite being phenomenally complex and powerful, could never do anything. It could be likened to a genius who sits in a study in his ivory tower generating excellent plans about how to order and improve his society. To achieve these plans he must listen to messengers coming from the outside world and employ workers to put his ideas into action. If he does not do these things, his ideas remain locked up in the tower and of no value to himself or anyone else.

The cerebral cortex, as noted above, is particularly vulnerable to damage by the causes of dementia, but many of the subcortical structures that lie beneath are not so badly affected, particularly during the mild to moderate phases of a dementia (although it is likely that there will be some degree of subcortical damage and that this will get worse as the condition progresses). With respect to the analogy above, the messengers are still bringing information in, and there are workers ready and able to do the work, but the plans they are working to are increasingly awry with respect to a full understanding of the world in which they are operating. It is with respect to this dynamic interplay between the most damaged and less damaged parts of the brain that the importance of attending to the psychosocial components of Kitwood’s equation becomes apparent. The remainder of this section will detail the particular functions of different regions of the cortex to provide the foundation upon which such interactions between brain damage and psychological and social factors can be understood.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree