Fig. 15.1

(a) Supraspinatus tendon, long axis (asterisk). Note the fibrillar appearance of tightly packed collagen fibers. (b) Supraspinatus tendon, short axis (asterisk). Note that in this cross-sectional axis, fascicles have a round or dot-like appearance

During an US examination , the transducer must be moved slowly and meticulously, so as not to miss any abnormalities. It is likewise paramount that the transducer body is always kept at 90° to the structure of interest, as any variation in this angle may alter the echogenicity of the structures of interest and result in false positives or false negatives due to an artifact named “anisotropy” [13]. Stability of the examiner’s hand is also important, and it is often found helpful if the examiner rests their fifth finger or lateral aspect of their palm on the patient’s skin during examination [3].

Sequence

For optimal positioning, the patient is asked to sit upright on a revolving chair, thus allowing for 360° access to the shoulder. The examiner stands at an angled position relative to the patient, thus allowing visualization of both the patient’s shoulder and the ultrasound monitor. In order to perform a complete assessment of the shoulder and visualize all pathology, a standardized sequence must be followed. Although this varies by examiner, a typical shoulder sequence includes the following: (1) evaluation of the long head of the biceps tendon; (2) evaluation of the subscapularis tendon with dynamic evaluation for subluxation/subluxation of the long head of the biceps tendon; (3) evaluation of the supraspinatus tendon, rotator interval, and subacromial-subdeltoid bursa; (4) evaluation of the infraspinatus and teres minor tendons; (5) evaluation of the posterior glenohumeral joint recess; (6) evaluation of the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and teres minor muscles; and (7) dynamic maneuvers to evaluate for subacromial impingement.

Evaluation: Long Head of the Biceps Tendon

The long head of the biceps tendon , comprised of both intra-articular and extra-articular components, is, as stated, typically the first structure that is evaluated. The intra-articular component originates from the supraglenoid tubercle and the glenoid labrum and traverses extrasynovially through the rotator interval. Upon exiting this interval, the tendon becomes extra-articular and resides within the bicipital groove between the greater and lesser tuberosities. The long head of the biceps is frequently affected in pathologic states of the rotator cuff. To evaluate this tendon, the seated patient is asked to keep their elbow flexed to 90°, with their hand fully supinated in order to achieve external rotation of the glenohumeral joint, thereby allowing the patient to present their bicipital groove anteriorly [9] (Fig. 15.2a).

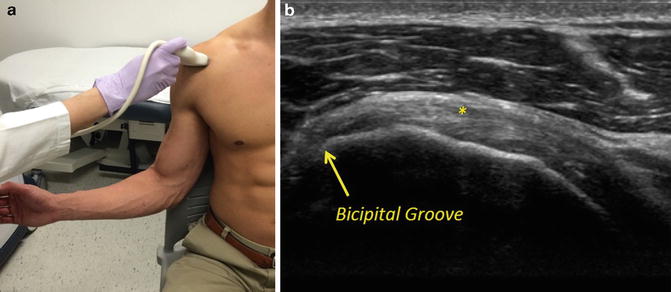

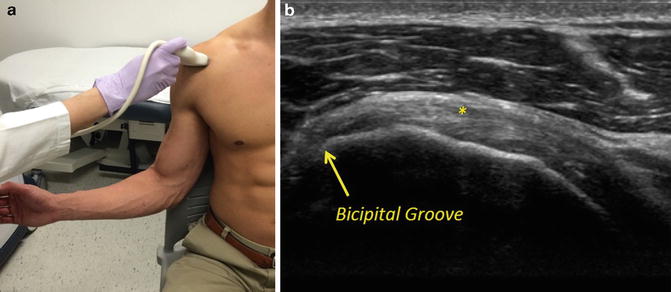

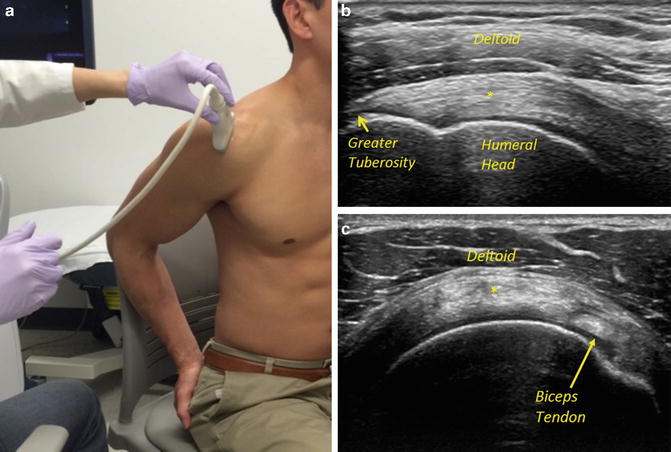

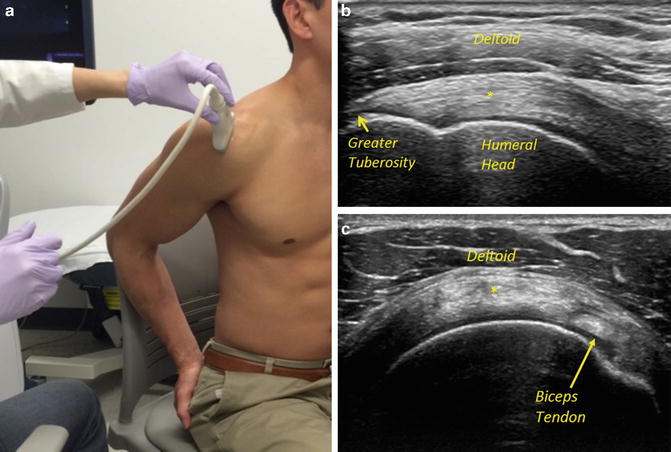

Fig. 15.2

(a) Patient positioning during examination of long head of the biceps tendon. Note that the elbow remains flexed, with the forearm supinated. (b) Normal long head of the biceps tendon, short axis (asterisk). (c) Normal long head of the biceps tendon, long axis (asterisk)

On US evaluation, the extra-articular component of the tendon is usually easily visualized, whereas its intra-articular segment is not. When the transducer is held perpendicularly to the orientation of the biceps (short axis), the tendon is seen as a hyperechoic, round structure between the supraspinatus and the subscapularis (Fig. 15.2b). Rotating the transducer so that it is parallel to the orientation of the tendon (long axis), the biceps takes on a narrow and striated appearance (Fig. 15.2c). This normal striation pattern can be often compromised, especially in setting of partial or complete tears, whereupon the longitudinal anechoic fissures can become apparent. A small amount of fluid surrounding the biceps is usually a normal finding; however, larger bicipital tendon sheath effusions signal either a glenohumeral joint effusion or bicipital tenosynovitis. Dynamic conditions, such as biceps instability, can likewise be evaluated by asking the patient to externally and internally rotate their shoulder while the transducer is held in place [11, 14].

Evaluation: Subscapularis Tendon

Following evaluation of the long head of the biceps tendon, the adjacent subscapularis tendon can be readily identified. This anterior and largest rotator cuff muscle originates within the subscapular fossa, courses anteriorly over the humeral head, and inserts on the lesser tuberosity. Innervated by the upper and lower subscapular nerves, the subscapularis facilitates internal rotation and adduction of the arm.

For ease of evaluation, the patient is asked to keep their elbow flexed at 90°. The shoulder is then externally rotated, allowing for visualization of the entire tendon, seen as a hyperechoic fibrillar structure inserting on the lesser tuberosity [6] (Fig. 15.3a, b).

Fig. 15.3

(a) Patient positioning during examination of subscapularis tendon. Note that the elbow is flexed and the shoulder is externally rotated. (b) Normal subscapularis tendon, long axis (asterisk)

It is important to note that the tendon typically courses superiorly and laterally. As such, for optimal visualization, a cranial tilt of the transducer is required [3]. Although pathology can occur at any point within the tendon, most subscapularis tendon tears originate at the superior portion of the tendon, and careful attention must be paid to this area when moving cranially to caudally during evaluation [9]. Dynamic evaluation can likewise help better delineate any tendinous retraction. With the transducer held in the short axis, gentle internal and external rotation of the arm allows for full evaluation of the tendon thickness as it courses toward the lesser tuberosity.

Evaluation: Supraspinatus Tendon

Evaluation of the supraspinatus tendon is of particular interest, as it is the rotator cuff tendon most frequently associated with tendinopathy or tears [4]. Originating from the supraspinous fossa on the superior aspect of the scapula and inserting onto the superior facet of the greater tuberosity of the humerus, the supraspinatus is innervated by the suprascapular nerve and functions to assist the deltoid in arm abduction.

Sonographic visualization is best completed with the patient’s arm in internal rotation and extension, thus presenting the supraspinatus anteriorly relative to the otherwise anechoic acromion. This is typically achieved with the patient’s arm placed in the Crass position (elbow flexed to 90°, forearm internally rotated to behind patient’s back). However, in patients with rotator cuff pathology, this degree of internal rotation may be difficult, and the modified Crass (patient’s palm placed over the ipsilateral buttock with the elbow flexed and directed medially) can be utilized [14] (Fig. 15.4a).

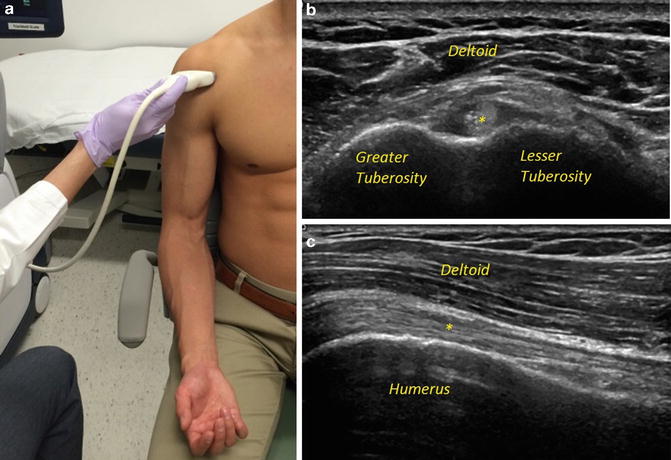

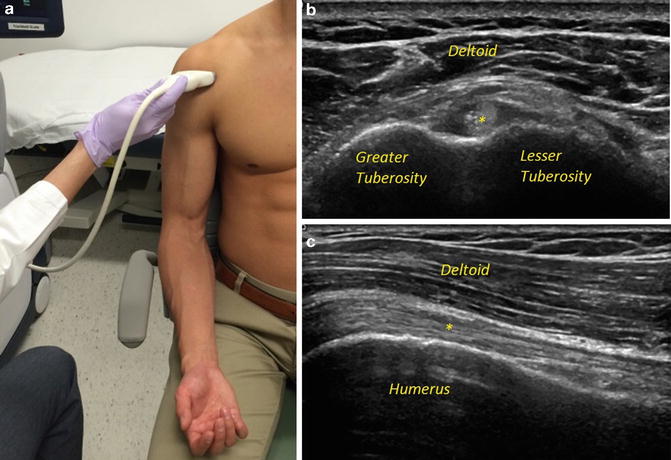

Fig. 15.4

(a) Patient positioning during examination of supraspinatus (modified Crass position). Note that the arm is extended and internally rotated. (b) Normal supraspinatus tendon, long axis (asterisk). Note the hyperechoic subacromial–subdeltoid bursa above supraspinatus tendon. (c) Normal supraspinatus tendon, short axis (asterisk)

As with identification of the subscapularis tendon, the long head of the biceps tendon can be used for orienting the examiner to the location of the supraspinatus, as both structures run adjacently and parallel to each other. When visualized longitudinally (long axis), the tendon should appear uniformly echogenic and it should taper as it approaches its insertion onto the greater tuberosity (Fig. 15.4b). Visualized transversely (short axis), the biceps tendon should be visualized just anterior to the supraspinatus tendon, within the rotator interval [3] (Fig. 15.4c). The subacromial–subdeltoid bursa, which resides just superficial to the supraspinatus tendon, is normally a thin hyperechoic structure, due to the presence of peribursal fat [13].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree