Fig. 19.1

Rupture of the medial collateral ligament in a basketball player

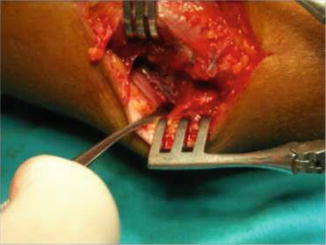

Fig. 19.2

Primary repair of the medial collateral ligament. Ulnar nerve behind the retractor left at the groove

Ulnar nerve dislocation was first described by Blattmann in 1851 [36]. This condition is referred to in the medical literature by various terms, including luxation, instability, hypermobility, and recurrent luxation/subluxation of the ulnar nerve [27, 36–38]. Each term has a unique origin and explanation and emphasizes a different clinical aspect of cubital tunnel syndrome. This rare nerve entrapment syndrome is caused by absence, rupture, or laxity of the epicondylo-olecranic ligament. Dysplasia of the retrocondylar ulnar groove also increases the likelihood of this condition [37].

Subluxation or dislocation of the ulnar nerve is uncommon in the general population, whereas it is reported with greater frequency in athletes that use their upper limbs for forceful and resisted flexion of the elbow joint [37, 39–41]. When the elbow is flexed, the nerve leaves its sulcus and is compressed by the medial humeral epicondyle. In athletes with well-developed upper limb muscles, the prominent medial head of the triceps pushes the nerve further out from the sulcus when flexing the elbow, which might cause rapid development of this pathology [42]. Subluxation/dislocation of the ulnar nerve from the ulnar groove can be palpated via elbow flexion and is often associated with a palpable click [43] (Figs. 19.3 and 19.4). Subluxation or dislocation of the nerve may predispose to neuropathy [35]. Subluxation of the ulnar nerve should be differentiated from a hypertrophic part of the medial head of the triceps snapping over the medial epicondyle during flexion [44] (Figs. 19.5 and 19.6).

Fig. 19.3

Ulnar nerve within the groove with the elbow in extension

Fig. 19.4

During flexion ulnar nerve dislocates medially. Note hypertrophy of the medial triceps

Fig. 19.5

Excision of redundant medial triceps muscle

Fig. 19.6

Subfascial transfer of the ulnar nerve

In athletes that perform the throwing motion, initial presentation of ulnar neuropathy may be pain along the medial joint line [1]. As inflammation progresses, they may also report clumsiness or heaviness of the fingers on the involved side as well as numbness and paresthesia in the fourth and fifth digits of the hand. Typically, these symptoms resolve with rest and are exacerbated by throwing or overhead activity. Athletes generally do not complain of weakness in the affected extremity—a late finding in ulnar neuropathy, as their performance is usually affected in the early stages before the development of motor changes. Painful popping or snapping sensations may also be experienced in those with recurrent nerve subluxation or dislocation [19].

Careful neurologic evaluation of the neck and upper extremity is mandatory to rule out more proximal causes of neuropathy [28, 31, 32]. Percussion along the ulnar nerve may elicit Tinel’s sign. A positive elbow flexion-compression test may elicit tingling that radiates toward the fifth digit, pain at the elbow, or medial forearm pain when manual pressure is directly applied over the ulnar nerve between the posteromedial olecranon and the medial humeral epicondyle as the elbow is maximally flexed [45]. The earliest sensory changes are noted via vibrometry or monofilament threshold testing. Nerve ending density test (e.g., two-point discrimination) becomes positive later, as the condition progresses. Motor weakness, if observed, starts earlier in the intrinsic hand muscles, such as the abductor digiti minimi and adductor pollicis. Intrinsic muscle motor fibers are situated more superficially within the ulnar nerve in the cubital tunnel and are thus more susceptible to injury [19].

Froment’s sign (hyperflexion of the thumb interphalangeal joint when attempting key pinch as the flexor pollicis longus is used in place of a paralyzed adductor pollicis) or Wartenberg’s sign (the inability to adduct the fifth digit due to unopposed ulnar insertion of the extensor digiti quinti) are positive only in more advanced ulnar neuropathy. Atrophy of the interossei muscles or hypothenar eminence can be difficult to observe in well-developed athletes. Extrinsic muscle weakness, involving the flexor digitorum profundus and FCU, is usually associated with more severe and advanced compression, as the extrinsic motor fibers lie deep within the ulnar nerve and thus are less exposed to damage [19]; clumsiness or loss of fine dexterity may occur in such cases. Inspection and palpation of the ulnar nerve should be performed along its course through the cubital tunnel to determine its location and stability. Palpation of the ulnar nerve in its groove throughout a full range of motion should be performed to identify subluxation or dislocation; the nerve may feel “doughy” or thickened [19]. Ulnar nerve hypermobility has been identified in 37 % of elbows and can be identified by asking the patient to actively flex the elbow with the forearm in supination, followed by placing a finger at the posteromedial aspect of the medial humeral epicondyle and asking the patient to actively extend the elbow. The ulnar nerve is observed to dislocate if trapped anterior to the examiner’s finger, to be perched if trapped beneath the finger, and to be stable if not palpable in the groove [38].

Diagnosis of cubital tunnel syndrome is based on a combination of clinical findings and electrodiagnostic test findings; however, in patients with clinical evidence of cubital tunnel syndrome, electromyography and nerve conduction velocities may have a false-negative rate of 10 %. False-negative electrodiagnostic test results may occur as few functional axons are required for a study to be interpreted as normal [46]. Negative tests, however, do not rule out the diagnosis of ulnar neuritis [31, 34]. Plain radiographs of the elbow, especially the cubital tunnel view, should be obtained in all patients to determine if there is elbow arthritis, which can lead to osteophytes and impingement on the cubital tunnel. In addition, radiographs may show signs of instability or previous trauma. Ultrasonography and MRI can be used to identify the presence of soft tissue masses that may compress the ulnar nerve as well as to evaluate the status of the surrounding soft tissue structures [19, 43, 47]. Dynamic sonography of the elbow may be useful for diagnosing ulnar nerve dislocation [37, 38, 48].

19.5 Treatment

Mild cubital tunnel syndrome can often be treated without surgery. There is a tendency for spontaneous recovery in patients with mild and/or intermittent symptoms if provocative causes can be avoided [46]. Nonsurgical management of ulnar neuropathy usually begins with rest, activity modification, ice, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Immobilization of the elbow for a brief period (2–3 weeks) may be necessary, especially in cases of ulnar nerve subluxation or dislocation. Local corticosteroid injection is not recommended. Although nonsurgical treatment has a high success rate in the general population, many athletes—especially those with associated valgus instability—experience recurrence of symptoms upon resumption of throwing and ultimately require surgical intervention. Indications for surgery include unsuccessful nonsurgical treatment, persistent ulnar nerve subluxation, symptomatic tension neurapraxia, and concomitant medial elbow problems that require surgery (e.g., valgus instability) [19].

Numerous surgical techniques have been described for the treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome, including simple in situ decompression of the cubital tunnel, anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve (subcutaneous, submuscular, or intramuscular), and medial humeral epicondylectomy with decompression of the ulnar nerve; however, there is a lack of consensus concerning which technique is superior [49]. Simple decompression and medial epicondylectomy are reported to yield poor results in athletes that perform the throwing motion and are not recommended. Simple decompression does not eliminate traction forces on the ulnar nerve, does not address pathological changes within the cubital tunnel, and cannot be performed in the presence of nerve instability. Medial epicondylectomy is associated with a high recurrence rate and destabilizes the nerve, which may predispose to subluxation or dislocation. In addition, injury to the MCL and the flexor-pronator musculature—important secondary dynamic stabilizers of the elbow—may occur and can lead to valgus instability of the elbow, with associated decreased forearm and wrist strength. Anterior subcutaneous transposition provides satisfactory results in athletes and has the advantage of minimizing disruption of the flexor-pronator musculature [50]. The subcutaneously transposed nerve, however, is vulnerable to direct trauma and may potentially develop instability [28, 31, 32]. In addition, the nerve may become secondarily compressed within the surgically created subcutaneous fasciodermal sling, leading to recurrence of symptoms.

Anterior submuscular transposition of the ulnar nerve decompresses all potential sites of entrapment and protects the transposed nerve from both direct and indirect trauma that may be encountered during athletic activity. The transposed nerve lies superficial to the pronator muscle mass and follows a direct course deep to the flexor muscle mass, where it lies adjacent to the median nerve in a fatty plane. This surgical approach also facilitates direct examination of the MCL and the underlying elbow joint for the presence of osteophytes, loose bodies, and other osseous abnormalities. In patients with concomitant valgus instability, repair or reconstruction of the MCL can be performed concurrently using the same approach [28, 31, 32, 34].

A potential disadvantage of submuscular ulnar nerve transposition is the long postoperative rehabilitation period necessary following detachment and reapproximation of the flexor-pronator origin, which must be healed before the resumption of throwing. After 1–2 weeks of immobilization, passive elbow range-of-motion exercises can begin. Active range-of-motion exercises are initiated 3–4 weeks postsurgery, followed by a strengthening program at 6 weeks. At 8 weeks’ postsurgery, a supervised throwing program, beginning with light tossing, is initiated. Full, unrestricted activity is usually achieved 4–6 months’ postsurgery [19].

19.6 Results

The outcome of anterior submuscular transposition of the ulnar nerve in athletes depends on the degree of preoperative ulnar nerve involvement and on the presence of associated medial elbow problems [34]. Patients with minimal sensory complaints and no motor weakness routinely recover completely and have an excellent prognosis with return to their previous level of function; however, poorer results have been observed in patients with advanced motor weakness and muscle atrophy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree