Ulcerative Colitis

W. Daniel Jackson

Stephen L. Guthery

Richard J. Grand

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic relapsing inflammatory disease of the colon and rectum of unknown origin. It was described first by Wilks and Moxon in 1875 as a chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) distinct from infectious colitis. After the recognition that the colon could be involved in patients with the regional enteritis described by Crohn and associates in 1932, criteria differentiating UC from Crohn colitis were established by 1960. Nonetheless, as many as 15% of cases of noninfectious chronic inflammatory colitis remain indeterminant. Therefore, this chapter should be read in conjunction with Chapter 353.

PATHOLOGY

The inflammation in UC is limited to the colon and rectum. Table 352.1 contrasts the patterns of pathologic involvement in UC and Crohn disease (CD). On the basis of these patterns, a distinction between the two entities usually can be made. The distal colon is affected most severely, and the rectum is involved in most patients with UC. Although 60% to 70% of these patients may present with universal or pancolitis, ultimately as many as 90% of children presenting by age 10 years may have inflammation of the entire colon. Inflammation is limited primarily to the mucosa and consists of continuous involvement along the length of the bowel, with varying degrees of ulceration, hemorrhage, edema, and regenerating epithelium. A recent study suggests that focal inflammatory changes may occur in early-onset UC. Although considered to be limited to the colon, inflammation may extend uninterrupted to the cecum and up to 25 cm into the terminal ileum as backwash ileitis without stenosis or distortion. In severe disease in which the mucosal epithelium has been destroyed, inflammation may extend beyond the muscularis mucosae into the submucosa. Intervening areas of granulation tissue and regenerating epithelium may form islands of tissue, termed pseudopolyps. Thickening of the bowel wall with fibrosis is a rare finding, although shortening of the colon and focal colonic strictures may occur in long-standing disease. Fistulas and perianal disease do not occur.

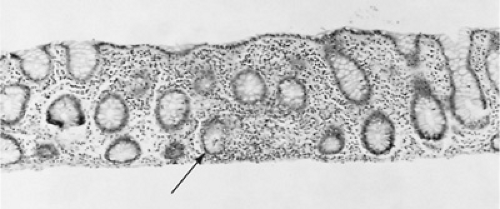

The histology of UC lesions demonstrates continuous acute and chronic inflammation with mucosal and submucosal infiltration by polymorphonuclear leukocytes and mononuclear cells rarely extending beyond the muscularis (Fig. 352.1). The colonic crypts show the most characteristic changes. Cryptitis and crypt abscesses characterize acute inflammation, which may lead to chronic changes of crypt distortion with branching and dropout, diminished goblet mucous cells, and Paneth cell metaplasia. No granulomas and little fibrosis occur.

ETIOLOGY

The origin of UC is unknown, but it involves a perpetuated dysregulated immune response that injures colonic epithelial elements. No convincing infective agent has been found, although the lesions resemble changes seen with infectious colitis, and luminal bacteria or their products may be implicated

in inducing and perpetuating the inflammatory response. Although no specific heritable patterns exist, 15% to 40% of patients may have other family members with IBD, with an incidence approximately ten times greater when a positive family history exists. However, concordance between monozygotic twins is only 20%, and human leukocyte antigen (HLA) markers (e.g., DR2) and linkages to other genetic syndromes (e.g., Hirschsprung, Down, and Turner) indicate that other factors, environmental and genetic, may determine susceptibility given a familial predisposition. Mutations in CARD15, an IBD susceptibility gene on chromosome 16, have been associated with CD but not UC. Other susceptibility loci for UC are being sought.

in inducing and perpetuating the inflammatory response. Although no specific heritable patterns exist, 15% to 40% of patients may have other family members with IBD, with an incidence approximately ten times greater when a positive family history exists. However, concordance between monozygotic twins is only 20%, and human leukocyte antigen (HLA) markers (e.g., DR2) and linkages to other genetic syndromes (e.g., Hirschsprung, Down, and Turner) indicate that other factors, environmental and genetic, may determine susceptibility given a familial predisposition. Mutations in CARD15, an IBD susceptibility gene on chromosome 16, have been associated with CD but not UC. Other susceptibility loci for UC are being sought.

TABLE 352.1. COMPARATIVE FEATURES OF ULCERATIVE COLITIS AND CROHN’S DISEASE | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Evidence exists of autoimmunity in terms of serum antibodies, immune complex complement activation, and lymphocytes directed against colonic epithelium and activated to release cytokine mediators of inflammation. The efficacy of glucocorticoids and other immunosuppressants in controlling the activity of UC certainly is related to attenuation of the immune response. Rodent models of colitis, especially the interleukin-2–deficient mouse, support a hypothesized derangement of T-lymphocyte immunoregulation, specifically loss of suppression of the inflammatory response to luminal antigens, including bacterial and food-related antigens.

The association of UC with a high familial prevalence of atopic diseases and with extraintestinal manifestations of erythema nodosum, arthritis, uveitis, and vasculitis supports the presence of genetic immunologic factors in the pathogenesis. However, data are insufficient at present to determine whether immune mechanisms have a primary causal or secondary perpetuating role. Allergic colitis rarely is seen after infancy and usually is transient. Evidence is insufficient for establishing an allergic origin for UC. No specific dietary practices have been implicated unequivocally in the cause or as risk factors.

Early gastroenteritis and lack of breast-feeding have been proposed as risk factors. Nonsmokers are overrepresented relative to CD, with nicotine proposed to have a therapeutic role only in UC. No data support a psychosomatic origin in terms of stress, personality type, or psychiatric illness, although emotional and other psychosocial factors may affect the presentation and course of the disease.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The incidence of UC in children appears to have reached a plateau after 1978. The incidence in the general population ranges from 4.1 to 7.3 cases per 100,000, with a prevalence ranging from 41.1 to 79.9 cases per 100,000 population. The disease is more prevalent in whites, with increased representation among those of Jewish backgrounds. UC occurs more commonly in northern Europe and North America, with an urban predominance. A recent review of cases in Wisconsin revealed that the incidence of UC in children may be as low as 2.14 cases per 100,000, and these investigators detected no ethnic, racial, familial, or urban predominance. Affected female patients outnumber affected male patients by approximately 50%. The distribution of age at onset is bimodal, with the major peak occurring in the second and third decades and a second peak in the fifth and sixth decades. Between 15% and 40% of all patients with UC present for evaluation before they reach age 20 years, with a peak onset occurring in adolescence. The incidence of UC in the 10- to 19-year-old age group has been estimated at 2 to 4 cases per 100,000 population. Approximately 20% of pediatric cases may present for evaluation by the time the children are age 10 years, with a mean age of approximately 6 years. The disease rarely occurs in children younger than 2 years old, although cases in infants have been reported. Most cases of noninfectious infantile colitis are caused by cow’s milk or soy protein allergy and are transient, with no proved relationship to later IBD.

BOX 352.1 Patterns of Presentation of Ulcerative Colitis

Extraintestinal (<5%)

Growth failure, arthropathy, erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum, occult fecal blood, elevated sedimentation rate, nonspecific abdominal pain, altered bowel pattern, cholangitis

Mild Disease (50%–60%)

Diarrhea, mild rectal bleeding, abdominal pain

No systemic disturbance

Moderate Disease (30%)

Bloody diarrhea, cramps, urgency, abdominal tenderness

Systemic disturbance: anorexia, weight loss, mild fever, mild anemia

Severe Disease (10%)

More than six bloody stools per day, abdominal tenderness with or without distention, tachycardia, fever, weight loss, significant anemia, leukocytosis, hypoalbuminemia

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

UC presents in at least four patterns that differ in the extent of mucosal inflammation and systemic disturbance (Box 352.1). The most common presentation is the insidious onset of diarrhea and hematochezia (overt rectal bleeding), usually without systemic signs of fever, weight loss, or hypoalbuminemia. In these patients, the disease often is confined to the distal colon and rectum; the physical examination is normal, without abdominal tenderness; and the course remains mild, with intermittent exacerbations.

Approximately 30% of patients have signs of moderate systemic disturbance and present with bloody diarrhea, cramps, urgency, anorexia and weight loss, malaise, mild anemia, and low-grade or intermittent fever. Physical examination may reveal abdominal tenderness, and stool shows varying amounts of blood and leukocytes.

The inflammation may progress to severe colitis in approximately 10% of cases, characterized by the following: more than six bloody stools per day, significant anemia often requiring transfusion, hypoalbuminemia caused by intestinal mucosal exudation, fever, tachycardia, and weight loss. The abdomen may be diffusely tender or distended. A subgroup of patients with severe colitis may not respond to medical therapy and may require early colectomy. Criteria for recognizing which patients may require surgery are presented in the later discussion on therapy.

Finally, extraintestinal manifestations of disease, including growth disturbance, may be presenting features and may precede as well as accompany overt gastrointestinal manifestations of colitis. The first sign of disease may be growth disturbance characterized by decreased linear growth velocity caused by subtle chronic dietary caloric deficits attributed to relative anorexia or to the increased metabolic demands of inflammation. Thyroid abnormalities have been discerned in patients with IBD. Nondestructive arthritis involving peripheral large joints may occur before and may not be correlated with intestinal symptoms. The skin lesions of erythema nodosum may be seen on the extensor surfaces of the arms and legs before colitis is recognized. Pyoderma gangrenosum, a severe necrotizing ulceration of skin, may evolve in areas of trauma, of surgical incisions, or around an ileostomy. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate may be elevated, suggesting a systemic inflammatory process, or stool examination may reveal occult blood and leukocytes because of the underlying colitis. Biochemical signs of liver involvement are uncommon. Approximately 4% of patients, predominantly those who have serology positive for perinuclear staining antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (pANCA), either develop or present with primary sclerosing cholangitis, characterized by fatigue, pruritus, and the gradual appearance of jaundice.

COMPLICATIONS

The most serious complication of UC, toxic megacolon, occurs in fewer than 5% of patients and is a medical and surgical emergency. In this entity, dilatation of the diseased colon is accompanied by fever, tachycardia, hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia, hypoalbuminemia, and dehydration. Leukocytosis with a predominance of immature neutrophils may be present. Some of these signs, particularly fever and tenderness, may be attenuated by high-dose corticosteroid treatment. The patient with toxic megacolon is at risk for development of colonic perforation, gram-negative sepsis, and massive hemorrhage. Effective monitoring requires supine and upright radiography to assess colonic caliber and to exclude the presence of intraabdominal free air, which would indicate perforation. Management should include stool bacterial culture, assay for Clostridium difficile toxins, and treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics and high-dose corticosteroids. Because most distention occurs in the anteriorly located transverse colon, positioning the patient in the prone position may be helpful. Patients who fail to respond promptly to aggressive medical measures require colectomy.

In patients with long-standing disease, colonic stricture may occur. In adults, it may be caused by carcinoma; in children, benign postinflammatory fibrotic stricture is more likely to be present. Intraabdominal and hepatic abscesses occur less often than in CD, except after perforation or colectomy.

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of UC is based on clinical presentation, radiologic findings, mucosal appearance, and histologic features, as well as on the exclusion of other known causes of colitis. A complete history should be obtained, with attention given to family history, exposure to infectious agents or antibiotic treatment, retardation in growth or sexual development, and extraintestinal manifestations. The physical examination should include assessment of hydration, nutritional status, and systemic and extraintestinal signs of chronic disease. The presence of fever, orthostasis, tachycardia, abdominal tenderness, distention, or masses indicates moderate to severe disease and the need for hospitalization. Disease activity indices have been developed to provide an objective scale for evaluating and measuring the severity or intensity of disease in patients with UC. These indices are based on frequency of stools, rectal bleeding, mucosal appearance, and physician global assessment (Box 352.2). Optimal evaluation and management will require coordination of care among the primary care physician, pediatric gastroenterologist, surgeon, psychosocial counselor, and family.

Laboratory Evaluation

A complete blood cell count discloses leukocytosis or anemia. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate is elevated in 60% to 70% of patients and is a marker of inflammatory activity. Electrolyte

disturbances are uncommon findings except in patients with dehydration, but serum protein and albumin levels may be low, indicating significant exudation. Because of either poor intake or losses from colonic inflammation and bleeding, levels of serum iron, zinc, and magnesium may be low. The low level of iron may be caused by elevated acute-phase proteins (transferrin) or may represent true deficiency or effects of chronic disease. Hypomagnesemia may prevent correction of hypocalcemia. Low alkaline phosphatase and cholesterol are indicators of depletion in zinc. Elevated serum transaminases, gamma-glutamyl transferase, and alkaline phosphatase may signify sclerosing cholangitis. Stool should be examined for blood, leukocytes, and ova and parasites. Culture of fresh stool should allow exclusion of Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter, toxigenic or hemorrhagic Escherichia coli, Aeromonas hydrophila, and Yersinia. Serologic titers may help to exclude Entamoeba histolytica. The colitis caused by the toxins of C. difficile may resemble the lesions in UC or CD or may complicate underlying IBD. An assay for C. difficile toxins should be obtained on all patients, regardless of prior antibiotic treatment. False-positive tests for C. difficile toxin A may be more common in severe colitis; if available, the cytotoxin B assay also should be requested. Finding a pathogen does not exclude underlying IBD in which the prevalence of secondary infections is increased.

disturbances are uncommon findings except in patients with dehydration, but serum protein and albumin levels may be low, indicating significant exudation. Because of either poor intake or losses from colonic inflammation and bleeding, levels of serum iron, zinc, and magnesium may be low. The low level of iron may be caused by elevated acute-phase proteins (transferrin) or may represent true deficiency or effects of chronic disease. Hypomagnesemia may prevent correction of hypocalcemia. Low alkaline phosphatase and cholesterol are indicators of depletion in zinc. Elevated serum transaminases, gamma-glutamyl transferase, and alkaline phosphatase may signify sclerosing cholangitis. Stool should be examined for blood, leukocytes, and ova and parasites. Culture of fresh stool should allow exclusion of Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter, toxigenic or hemorrhagic Escherichia coli, Aeromonas hydrophila, and Yersinia. Serologic titers may help to exclude Entamoeba histolytica. The colitis caused by the toxins of C. difficile may resemble the lesions in UC or CD or may complicate underlying IBD. An assay for C. difficile toxins should be obtained on all patients, regardless of prior antibiotic treatment. False-positive tests for C. difficile toxin A may be more common in severe colitis; if available, the cytotoxin B assay also should be requested. Finding a pathogen does not exclude underlying IBD in which the prevalence of secondary infections is increased.

BOX 352.2 Ulcerative Colitis Disease Activity Index

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree