20 Tumours of the musculoskeletal system and pathological fractures

Cases relevant to this chapter

Essential facts

1. A soft-tissue lump is likely to be sarcoma if it is painful, growing rapidly, larger than 5 cm in size and deep to deep fascia.

2. Metastatic bone tumours occur at any age, but are the most frequent cause of a painful lytic bony lesion in the elderly. Sclerotic lesions occur in prostate and breast cancer.

3. Pathological fractures occur after minimal force; they include osteoporotic fractures in the elderly, osteogenesis imperfecta in the young, fractures through infected or dead bone, and fractures through neoplastic bony lesions.

4. The matrix of a benign cystic lesion is purely lytic, and the margins are well defined; malignant lesions and rapidly growing benign lesions have infiltrative edges.

5. Avoid fixation of a pathological fracture before obtaining a definitive diagnosis.

6. Most malignant pathological fractures will not heal; therefore, the implant should be ‘load-bearing’ rather than ‘load-sharing’.

7. Malignant bone tumours are best managed within a multidisciplinary team.

Tumours

Neoplastic (benign)

Important benign neoplasms of soft tissue are listed in Table 20.1; they are far more common than malignant ones.

Table 20.1 Benign neoplasms of soft tissue

| Tumour | Features |

|---|---|

| Lipoma | Very common. MRI features usually typical fat but may be difficult to discriminate atypical lipoma from low-grade liposarcoma |

| Aggressive fibromatosis (desmoid tumour) | Locally difficult to resect completely. Resolution over many years. Radiotherapy, tamoxifen, vitamin C may help |

| Myxoma | Difficult to resect locally and may recur after many years. Occasionally de-differentiates to myxoid sarcoma |

| Leiomyoma | In retroperitoneum and gastrointestinal tract may have malignant potential |

| Haemangioma | May be congenital or acquired. Large ones in children may require multidisciplinary approach because of skin involvement |

| Schwannoma | Usually benign on a major nerve. Can be ‘shelled’ away from the nerve without damage |

| Neurofibroma | Integral within the nerve and cannot easily be ‘shelled’ away from it |

| Synovial chondromatosis | Forms in large joints and is difficult to eradicate. May de-differentiate to chondrosarcoma |

| Giant cell tumour of tendon sheath | Forms on tendons and easily ‘shells’ away from them |

Benign tumours of bone usually grow slowly and, therefore, tend to have a well defined margin. The bone has chance to react and often does so by expansion with cortical changes. Treatment is frequently a biopsy-cum-curettage to remove the majority of macroscopic tumour without causing morbidity. In most benign bone tumours, this allows bone healing to eradicate remaining microscopic tumour. Important examples of benign bone neoplasms are listed in Table 20.2.

Table 20.2 Benign neoplasms of bone

| Tumour | Radiographic Features | Clinical Features/Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Simple (unicameral) bone cyst | Large, expanded, well demarcated, lytic metaphyseal lesion | Children. Heals spontaneously after fracture or may require bone graft |

| Aneurysmal bone cyst | Large lytic metaphyseal lesion | Blood-filled spaces. Curettage necessary |

| Giant cell tumour of bone | Metaphyseal to articular surface. Aggressive appearance | Solid tumour with soft-tissue involvement. Bony destruction results in extended joint replacement surgery |

| Eosinophilic granuloma (Langerhans’ cell disease) | May have aggressive appearance | Part of a systemic disorder of histiocytes. Check anterior pituitary function |

| Osteoid osteoma | Cortical lesion. Central nidus with lytic ring and surrounding sclerosis | Children and young adults. Osteoid-producing tumour. Painful. May be curetted or ablated using heat under CT control |

| Osteoblastoma | Large lytic metaphyseal lesion | Similar to osteoid osteoma over 2 cm in size |

| Chondroblastoma | Epiphyseal | Curettage and bone grafting |

| Fibrous cortical defect | Bubbly, lytic within cortex. Little change with time | Curettage if large and painful |

Neoplastic (malignant)

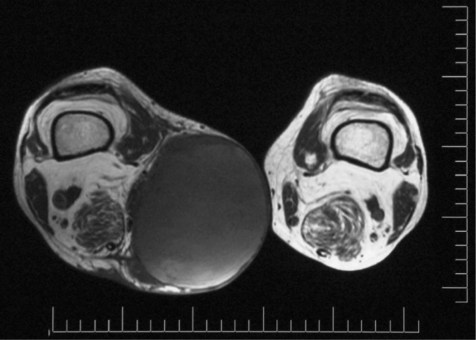

A patient who presents with a soft-tissue lump has a high (>90%) risk of this being a sarcoma if it is: (a) painful, (b) growing rapidly, (c) larger than 5 cm in size and (d) deep to deep fascia. Figure 20.1 shows a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of a large soft-tissue sarcoma demonstrating most of these features. An X-ray may provide evidence of calcification (calcified haematoma, possibly synovial sarcoma). MRI defines solid from cystic and identifies a solid focus for biopsy, which should be undertaken only by the surgical team that will undertake the definitive surgery, or a competent radiologist. Nowadays these multidisciplinary teams exist in teaching hospitals accredited as regional or national centres for sarcoma care. The histopathologist should identify the lesion through haematoxylin and eosin staining and immunohistochemistry to subtype the biopsy specimen. Cytogenetics may be useful. It should be remembered that the biopsy may not be representative of the entire specimen. Following a diagnosis of sarcoma, further ‘staging’ investigations would include blood tests (full blood count, clinical chemistry, clotting screen, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP)) and computed tomography (CT) of the chest to identify any lung metastases.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree