Tularemia

Richard F. Jacobs

Tularemia is an acute, febrile, zoonotic illness caused by the grain-negative bacterium Francisella tularensis. Tularemia is distributed widely in the northern hemisphere, with numerous infections occurring in humans over relatively large areas of the United States, Europe, and Asia. Tularemia is a disease of small animals, but humans are highly susceptible hosts.

MICROBIOLOGY

F. tularensis is a small, nonmotile, gram-negative coccobacillary organism that requires cysteine for growth. In 1959, F. tularensis was divided into two types: F. tularensis subspecies tularensis (type A) and F. tularensis subspecies palaearctica (type B) are the official nomenclatures.

F. tularensis tularensis, found predominantly in North America, is highly virulent, causing severe disease in mammals and mild to severe disease in humans. F. tularensis palaearctica has been identified in Asia, Europe, and North America. The species frequently is linked to environmental sources and waterborne diseases of rodents and appears to be less virulent in mammals. Descriptions of strains of the organism in Central Asia and Japan added further complexity to the subspecies differentiation. Apparently, the biochemical characteristics and virulence of F. tularensis strains do not reflect their genetic character, as judged by molecular techniques using 16S rRNA. Strains isolated from the Central Asian area of the former Soviet Union and Japan belong to genotype A, although the virulence and some of the biochemical characteristics conform to those of the genotype B strains, which means that strains of F. tularensis tularensis are not restricted to the North American continent. However, the highly virulent strains of the organism possibly are restricted to North America.

The organism can be cultured on media using glucose-cysteine agar, a temperature of 37°C, and a pH of 6.9, but selected media may be necessary for optimal growth. Clinicians should be aware that the organism does grow on routine blood and wound cultures (e.g., lymph node aspirate), which

may present a health hazard in the microbiology laboratory because of aerosolization among laboratory workers. Because as few as ten organisms have been shown to induce experimental infection in humans, biosafety level 2 is recommended for clinical laboratory work. Clinicians should notify the laboratory if tularemia is included in the differential diagnosis. All strains of F. tularensis appear to be serologically identical. Despite this serologic homogeneity, future epidemiologic studies will implement molecular identification using 16S rRNA to divide the isolates into genotypes A and B.

may present a health hazard in the microbiology laboratory because of aerosolization among laboratory workers. Because as few as ten organisms have been shown to induce experimental infection in humans, biosafety level 2 is recommended for clinical laboratory work. Clinicians should notify the laboratory if tularemia is included in the differential diagnosis. All strains of F. tularensis appear to be serologically identical. Despite this serologic homogeneity, future epidemiologic studies will implement molecular identification using 16S rRNA to divide the isolates into genotypes A and B.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

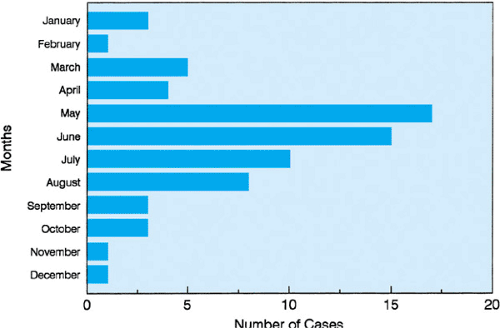

F. tularensis is a ubiquitous organism found in the Northern Hemisphere between 30 and 71 degrees northern latitude. It has been reported throughout the United States, but it occurs most commonly in the western and south central states, with the highest incidence in regions of Oklahoma, Missouri, Arkansas, Louisiana, Tennessee, Texas, Illinois, and Virginia. Although the incidence peaks during the late spring through the summer months, the year-round distribution of cases probably reflects the multiple vectors of transmission of this organism (Fig. 177.1). The major vector of F. tularensis is the tick, and the disease is seen primarily in children and young adults during the major tick seasons of spring, summer, and early fall. The disease is transmitted to humans by vector (e.g., ticks, lice, fleas, deer flies, mosquitoes), animal bites, or ingestion of infected, inadequately cooked animal tissues or contaminated water. Amblyomma americanum (Lone Star tick), Dermacentor andersoni (wood tick), and Dermacentor variabilis (dog tick) are the main reservoirs for F. tularensis. Inhalation of the organisms, which occurs primarily while working in or being exposed to contaminated land or water or both (Scandinavia), skinning animal carcasses, and working with the organism in the microbiology laboratory, has been identified as a common cause of tularemia pneumonia. It may be transferred mechanically by claws or teeth of domestic pets that have preyed on infected animals. Rabbits, hares, muskrats, voles, rats, mice, and more than 100 other animal species harbor F. tularensis. Cases of infection in older children and adults in the winter months typically are associated with rabbit or deer hunting or contamination through contact with infected animal tissues.

Contrary to earlier reports of tularemia as “rabbit fever,” tick exposure is the vector for 71% of pediatric and adults cases. The reported incidence of rabbit exposure is similar for adults (11%) and children (7%). Tularemia in children has been documented after a cat bite, a squirrel bite, and exposure to other domestic animals.

PATHOGENESIS

F. tularensis gains access to the human body through the skin, conjunctiva, oropharynx, respiratory tract, or gastrointestinal tract. It spreads by lymphatics or hematogenously, and bacteremia usually develops during the first week of infection. Skin, regional lymph nodes, liver, spleen, and lungs can be involved, and the lesions can occur in the gastrointestinal tract and the central nervous system.

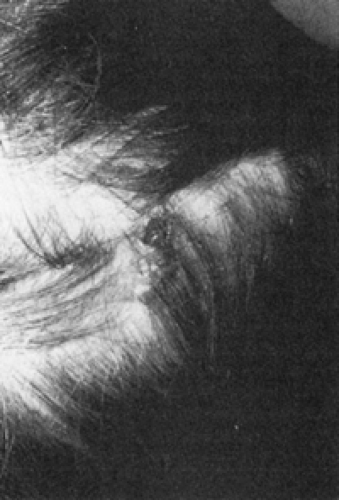

The classic lesion is one of focal necrosis and granuloma formation. After a tick bite, a hallmark presentation for F. tularensis infection is the resultant eschar, ulcer, or papule with regional lymphadenitis (Fig. 177.2). The organism elicits humoral and cell-mediated immune responses, but seroconversion may take 1 or 2 weeks after infection. Despite reports of recurrent disease, the initial infection with F. tularensis usually confers lasting immunity.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

The average incubation period for tularemia is 3 to 4 days (range, 1 to 21 days). The onset of symptoms usually is abrupt, with a temperature usually greater than 39.4°C (103°F), chills, pharyngitis, myalgias, arthralgias, nausea and vomiting, and, occasionally, headache, cough, and photophobia. The predominant signs of tularemia include the following: regional lymphadenopathy or lymphadenitis; an ulcer, eschar, or papule at the site of tick embedment; and hepatosplenomegaly. Some patients develop conjunctivitis (Table 177.1). In untreated cases of tularemia, fever may persist for 2 to 3 weeks or longer. No characteristic peripheral blood profile has been established for

tularemia. Various skin rashes (macular, morbilliform, pustular, and erythema nodosum) have been described, but the predominant feature is regional lymphadenopathy or lymphadenitis. Subcutaneous nodules have been reported.

tularemia. Various skin rashes (macular, morbilliform, pustular, and erythema nodosum) have been described, but the predominant feature is regional lymphadenopathy or lymphadenitis. Subcutaneous nodules have been reported.

FIGURE 177.2. A papule with an ulcerative base on the scalp of a child with ulceroglandular tularemia presenting with fever and unilateral cervical lymphadenitis. |

TABLE 177.1. CLINICAL TYPES AND PRESENTATION OF TULAREMIA IN CHILDREN | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree