Tricks and Tips

The wildest broncos are those you rode somewhere else.

This chapter will concentrate on nuggets of useful information that fall into one of three categories of fascinating factoids:

ANATOMIC FACTOIDS

Recognizing Normal Anatomy

Subacromial Anatomy

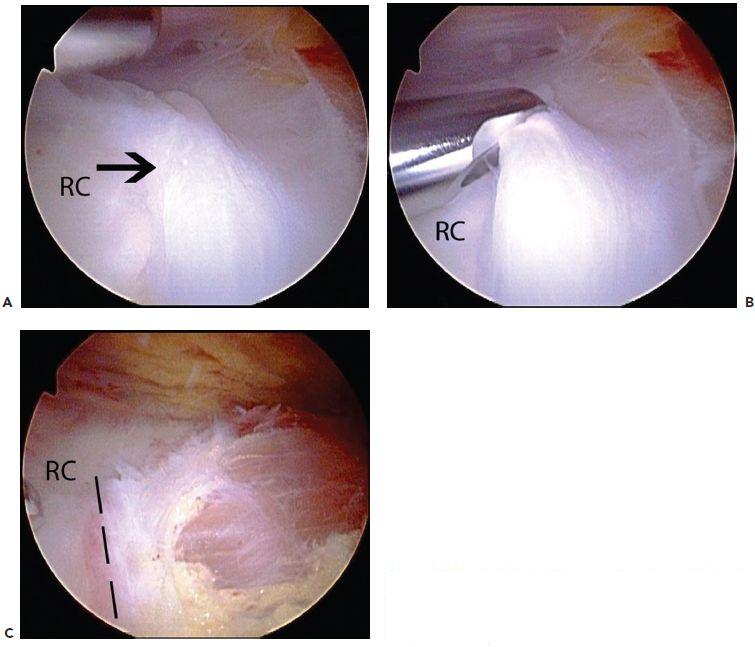

- The medial border of the subacromial bursa is located at the musculotendinous junction of the supraspinatus. Debriding the medial “curtain” of the subacromial bursa will reveal the supraspinatus muscle belly (Fig. 24.1).

- The subacromial “space,” in which visualization is easily accomplished, underlies the anterior half of the acromion. The posterior half of the subacromial space is filled with dense fibrofatty tissue that must be debrided in order to visualize the structures in that area.

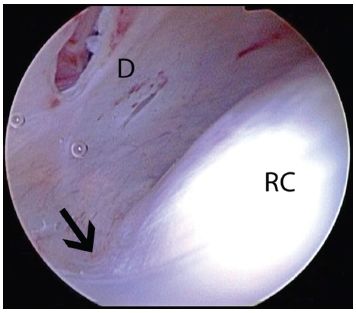

- The lateral gutter has a “blind pouch” at its lower extent, which is the lower limit of the subacromial bursa. All of the axillary nerve branches lie below that “blind pouch,” which represents a good anatomical landmark for the limits of safe dissection in the lateral gutter (Fig. 24.2).

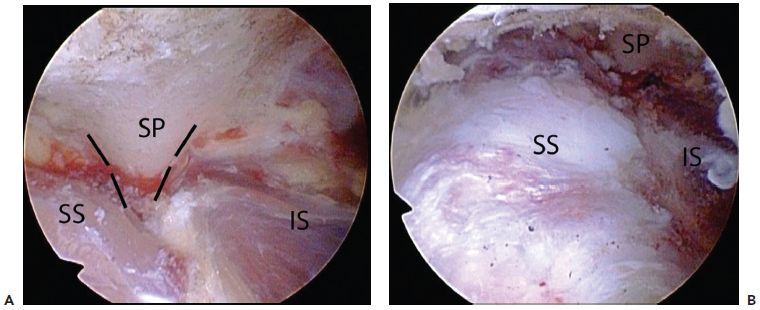

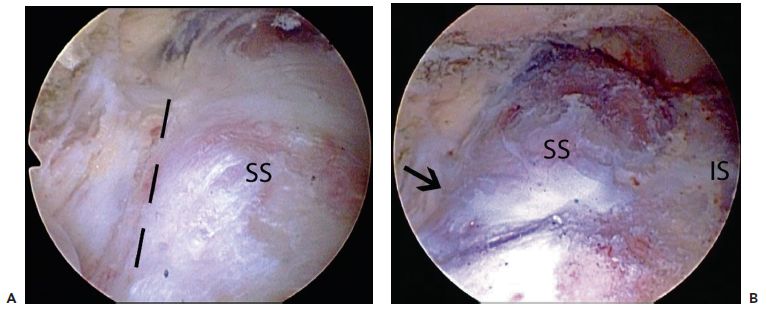

- The scapular spine defines the border between the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscle bellies. Just lateral to the scapular spine, there is a raphé that continues to define that border (Fig. 24.3).

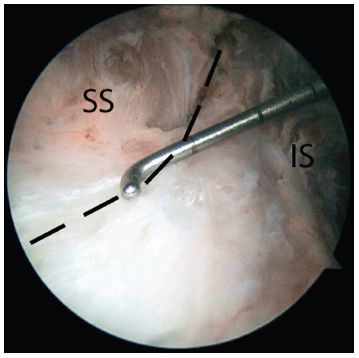

- At the posterior aspect of the greater tuberosity, the tendon of the infraspinatus curls anterolaterally over the top of the supraspinatus tendon and is usually distinctly visible (Fig. 24.4).

- The anterior border of the supraspinatus is visible as a thickened tendon that borders the thinner rotator interval tissue (Fig. 24.5).

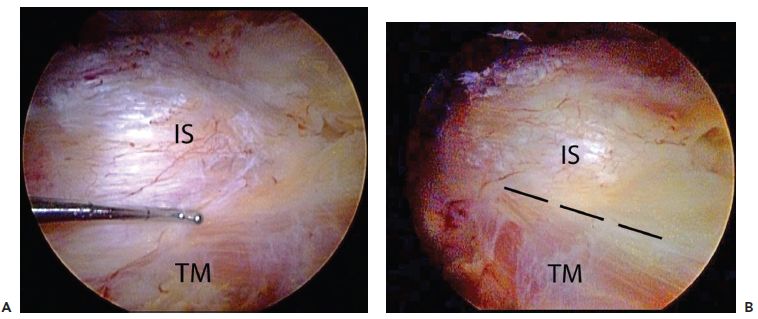

- The teres minor muscle belly extends much further laterally than the infraspinatus muscle belly and can be distinguished as a separate distinct muscle on that basis (Fig. 24.6).

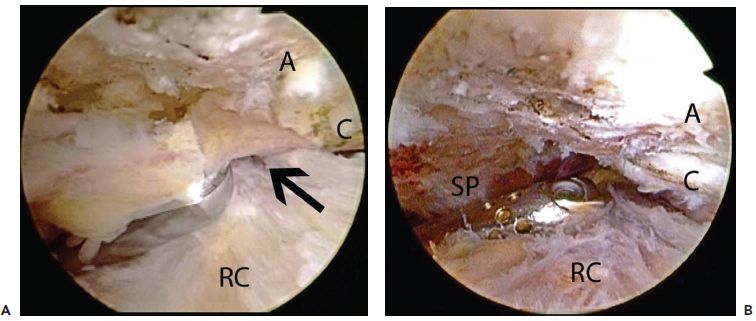

- There is a fat pad overlying the supraspinatus muscle belly, just posterior to the acromioclavicular (AC) joint. This fat pad must be debrided in order to optimally visualize the AC joint (Fig. 24.7).

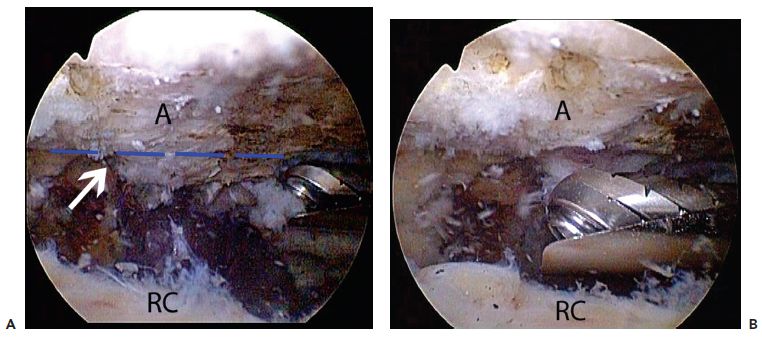

- When viewed from a posterior viewing portal, the anterior acromion typically has a medial “notch” that lies at the same level as the undersurface of the distal clavicle. This notch is an excellent “target” to aim for when doing an arthroscopic acromioplasty (Fig. 24.8).

Intra-articular Anatomy

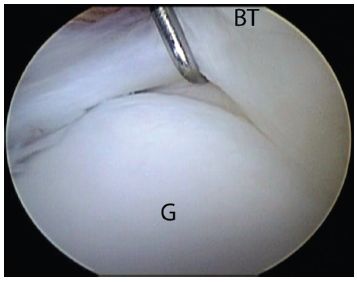

- Beneath the superior labrum, the articular cartilage normally extends 2 to 3 mm medial to the corner of the superior glenoid (Fig. 24.9).

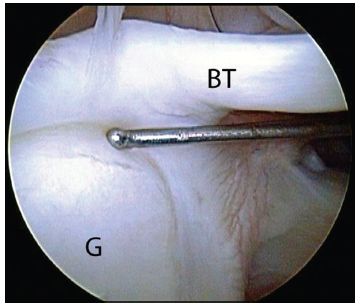

- The root of the biceps should feel stable to palpation with a hook probe, with the tactile feedback that the biceps fibers are well anchored to the bone beneath the biceps (Fig. 24.10).

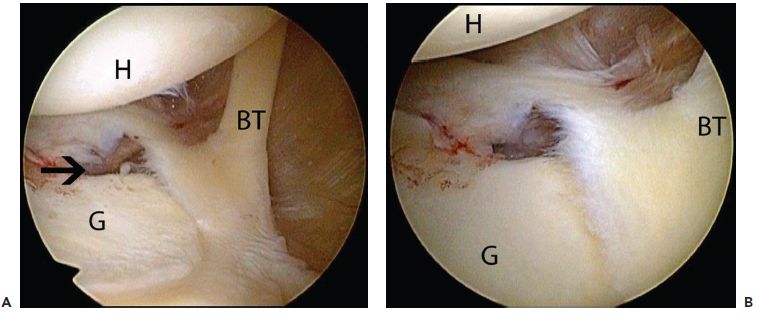

- The Buford complex comprises a cord-like middle glenohumeral ligament and absence of a labrum between the midglenoid notch and the biceps root (Fig. 24.11).

- A sublabral foramen is a normally occurring hole beneath the portion of the labrum that lies between the midglenoid notch and the biceps root. This is distinguishable from the Buford complex because the labrum is present and the middle glenohumeral ligament is a normal band rather than appearing cord-like (Fig. 24.12).

- From an anterosuperolateral viewing portal, the arc of the humeral head should be centered on the bare spot of the glenoid (Fig. 24.13).

- Biceps anomalies do not require treatment. Examples of biceps anomalies are:

- Bifid long head of the biceps, where one head inserts into the superior labrum and the other head inserts into the rotator cuff (Fig. 24.14).

- Hypoplastic biceps (Fig. 24.15).

- Bifid long head of the biceps, where one head inserts into the superior labrum and the other head inserts into the rotator cuff (Fig. 24.14).

- The axillary nerve lies closest to the glenoid at 5 o’clock and 7 o’clock. It can often be seen in those locations after arthroscopic capsular release (e.g., for adhesive capsulitis) (Fig. 24.16).

Figure 24.1 A: Left shoulder, posterior subacromial viewing portal, demonstrates the medial reflection of the subacromial bursa (black arrow). B: A shaver is used to debride the bursal reflection. C: Following debridement, the musculotendinous junction (dashed lines) is visible. RC, rotator cuff.

Figure 24.2 Left shoulder, posterior subacromial viewing portal, demonstrates the normal lateral gutter of the subacromial space. The axillary nerve always lies below the lateral bursal reflection (arrow). Consequently, lateral dissection should be limited to the level of the lateral bursal reflection. D, internal deltoid fascia; RC, rotator cuff.

Figure 24.3 A: Left shoulder, lateral subacromial viewing portal, demonstrates the scapular spine (outlined by dashed lines). The scapular spine defines the interval between the supraspinatus tendon and the infraspinatus tendon. B: Profile view in the same shoulder. IS, infraspinatus tendon; SP, scapular spine; SS, supraspinatus tendon.

Figure 24.4 Left shoulder, lateral subacromial viewing portal, demonstrates the normal infraspinatus tendon insertion. Note that the anterior insertion of the infraspinatus is not directly lateral to the line of its fibers, but rather curves anterolaterally to its insertion onto the greater tuberosity (dashed line indicates anterior margin of infraspinatus). IS, infraspinatus; SS, supraspinatus.

Figure 24.5 A: Left shoulder, lateral subacromial viewing portal. The anterior margin of the supraspinatus tendon (dashed black lines) has a thickened edge that can be used to define it from the rotator interval. B: Same shoulder again demonstrates the thickened anterior border (black arrow). IS, infraspinatus tendon; SS, supraspinatus tendon.

Figure 24.6 A: Left shoulder, posterior viewing portal. A probe marks the border between the infraspinatus and teres minor. B: Same shoulder, demonstrates how the muscle belly of the teres minor extends further lateral than that of the infraspinatus. The dashed lines outline the interval between the infraspinatus and teres minor. IS, infraspinatus tendon; TM, teres minor tendon.

Figure 24.7 A: Right shoulder, lateral subacromial viewing portal, demonstrates use of a shaver to clear the fibrofatty tissue that lies posterior the AC joint and also covers the scapular spine. This tissue must be removed in order for the AC joint to be viewed from a posterior portal. B: Same shoulder following removal of the fibrofatty tissue. An arthroscope introduced from a posterior portal now has an unobstructed view of the AC joint. A, acromion; C, clavicle; RC, rotator cuff; SP, scapular spine.

Figure 24.8 A: Right shoulder, posterior subacromial viewing portal, demonstrates use of a burr to perform an acromioplasty. The medial acromion typically has a notch (white arrow) that is level with the distal clavicle. The apex of this notch is often a good landmark for the plane of resection (dashed blue line) during an acromioplasty. B: Same shoulder demonstrates a flat acromion following the resection to the apex of the notch. A, acromion; RC, rotator cuff.

Figure 24.9 Left shoulder, posterior viewing portal, demonstrates a normal superior labral recess. The articular cartilage normally extends 2 to 3 mm medial to the superior glenoid. BT, biceps tendon; G, glenoid.

Figure 24.10 Left shoulder, posterior viewing portal. A probe introduced from an anterior working portal demonstrates a stable biceps root. BT, biceps tendon; G, glenoid.

Subscapularis–Biceps–Subcoracoid Space

- The normal subscapularis tendon does not have any linear longitudinal splits (Fig. 24.17).

- The coracoid tip generally lies just anterior to the upper border of the subscapularis. A “rolling wave” of indentation of the subscapularis/rotator interval junction can often be seen with internal and external rotation of the humerus. This indentation is caused by the coracoid tip (Fig. 24.18).

- There is normally a 2 to 3 mm bare strip (i.e., devoid of articular cartilage) just medial to the footprint of the subscapularis (Fig. 24.19).

- The subscapularis and proximal bicipital groove are best visualized with a 70° arthroscope. The upper 2.5 cm of the bicipital groove can be visualized in this way (Fig. 24.20).

- When viewed with a 70° scope, the biceps tendon should lie anterior to the plane of the subscapularis tendon (Fig. 24.21).

- To locate and visualize the coracoid, make a window in the rotator interval just above the upper border of subscapularis, palpate the coracoid, then clear the soft tissues from the bone (Fig. 24.22).

- Viewing with a 70° scope through the window in the rotator interval, the entire coracoid can be seen in a panoramic way by rotating the light cable. The normal coracoid tip should not have an osteophyte projecting posterior to the plane of the conjoined tendon, and the space between the coracoid tip and the subscapularis tendon should be at least 7 mm. This space can be measured by comparison with a shaver or burr of a known diameter (Fig. 24.23).

Figure 24.11 Left shoulder, posterior glenohumeral viewing portal, demonstrates (A) panoramic and (B) up-close views of a Buford complex that is characterized by a cordlike middle glenohumeral ligament with absence of the labrum between the biceps root and the midglenoid notch (black arrow). BT, biceps tendon; G, glenoid; H, humerus.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree